Visconti of Milan

| Visconti | |

|---|---|

Coat of arms of the Visconti of Milan | |

| Country | |

| Etymology | vice: "deputy" - comes: "count" |

| Place of origin | Milan |

| Founded | 1075 |

| Founder | Ariprando Visconti |

| Final ruler | Filippo Maria Visconti |

| Titles |

|

| Motto | Vipereos mores non violabo ("I will not violate the customs of the serpent") |

| Cadet branches | Visconti di Modrone |

The Visconti of Milan are a noble Italian family. They rose to power in Milan during the Middle Ages where they ruled from 1277 to 1447, initially as Lords then as Dukes, and several collateral branches still exist. The effective founder of the Visconti Lordship of Milan was the Archbishop Ottone, who wrested control of the city from the rival Della Torre family in 1277.[1]

Origins

[edit]The earliest members of the Visconti lineage appeared in Milan in the second half of the 11th century. The first evidence is on October 5, 1075, when Ariprando Visconti and his son Ottone ("Ariprandus Vicecomes", "Otto Vicecomes filius Ariprandi") attended and signed together some legal documents in Milan.[2] Ariprando Visconti's family is believed to have pre-existed in Milan and obtained the title of viscount, which became hereditary throughout the male descent.[3][4]

In the years following 1075, Ottone Visconti is shown in the proximity of the Salian dynasty's sovereigns, Henry IV and his son Conrad. His death's circumstances confirm the relationship with the imperial family. In 1111 in Rome, Ottone was captured and executed after attempting to defend Henry V from an assault.[a][b][7] In the first documents where they appear, Ottone and his offspring declared that they abided by the Lombard law and acted in connection with other Milanese families of the noble upper class (capitanei).[8] A relationship with the Litta, a Milanese vavasour family subordinate to the Visconti in the feudal hierarchy, is also documented.[9][10] These circumstances demonstrate their participation in the Milanese society in the years before 1075 and, ultimately, their Lombard origin.[11]

In 1134, Guido Visconti, son of Ottone, received from the abbot of Saint Gall the investiture of the court of Massino,[12] a strategic location on the hills above Lake Maggiore, near Arona. Here, another family member was present in the second half of the 12th century as the castellan (custos) of the local archiepiscopal fortress.[13] In 1142, King Conrad III confirmed the investiture in a diploma released to Guido in Ulm.[14] Another royal document, issued by Conrad III in 1142 as well, attests to the Visconti's entitlement to the fodrum in Albusciago and Besnate.[15] Based on a document issued in 1157, the Visconti were considered holders of the captaincy of Marliano (today Mariano Comense) since the time of archbishop Landulf;[16] however, the available documentation cannot infer such a conclusion.[17]

A second Ottone, son of Guido, is attested in the documentary sources between 1134 and 1192. The primary role of Ottone in the political life of the Milanese commune emerges in the period of the confrontation with Frederick Barbarossa: his name is the first to be cited, March 1, 1162, in the group of Milanese leaders who surrendered to the emperor after the capitulation of the city that took place in the previous weeks.[18][19] A member of the following generation, Ariprando, was bishop of Vercelli between 1208 and 1213 when he also played the role of Papal legate for Innocent III. An attempt to have him elected archbishop of Milan failed in 1212 amidst growing tensions between opposite factions inside the city. His death in 1213, was probably caused by poisoning.[20]

The family dispersed into several branches, some of which obtained fiefs far off from Milan. Among them, the one that gave origin to the lords and dukes of Milan allegedly descended from Uberto, who died in the first half of the 13th century.[21] The other branches' members frequently added to their surname the name of the place where they chose to live and where a fortification was available for their residence. The first of such cases were the Visconti di Massino, the Visconti di Invorio, and the Visconti di Oleggio Castello.[22] In these localities, a castle (Massino), its remains (Invorio), or a later reconstruction of the initial building (Oleggio Castello) are still visible today.

Lords and Dukes of Milan

[edit]The Visconti ruled Milan until the early Renaissance, first as Lords, then, from 1395, with the mighty Gian Galeazzo, who endeavored to unify Northern and Central Italy, as Dukes. Visconti's rule in Milan ended with the death of Filippo Maria Visconti in 1447. He was succeeded by a short-lived republic and then by his son-in-law Francesco I Sforza, who established the reign of the House of Sforza.[23]

Rise to the lordship

[edit]When Frederick II died in 1250, the war engaged by the Lombard League and Milan against him ended. Inside the Milanese commune, united in its defense until then, conflicts between rival factions began. The Della Torre family progressively acquired power in Milan after 1240, when Pagano Della Torre assumed the leadership of the Credenza di Sant'Ambrogio, a political party with a popular base. This position allowed them to have a role in the tax collection of the commune (estimo), which was essential to finance the war against Frederick II while affecting the great landowners. In 1247, Pagano was succeeded by his nephew Martino Della Torre. The commune created the new role of Senior of the Credenza (Anziano della Credenza) for him to underline his authority. In this position, the Della Torre began to clash with the Milanese noble families organized in their political party, the Societas Capitaneorum et Valvassorum, having the Visconti among the most prominent figures. After unrest between the opposite parties, the so-called Sant'Ambrogio Peace was signed in 1258 among the parties, strengthening the position of La Credenza and La Motta (a second political party with popular tendencies).[24][25]

New events in favor of the Della Torre undermined the Sant'Ambrogio Peace. At the end of 1259, Oberto Pallavicino, a former partisan of Frederick II who got closer to the Guelph positions of the Della Torre, was appointed by the Milanese commune for five years as General Captain of the People. His victory in the Battle of Cassano on 16 September 1259 against Ezzelino da Romano, formerly his ally on the Ghibelline side in the war of Frederick II against the Lombard communes, enhanced his position in Milan. The nobles expelled from the city during the clashes preceding the Sant'Ambrogio Peace placed their hopes on Ezzelino to regain their old power.[26][27][28]

A decisive event in the confrontation between the Della Torre and the Visconti factions was the appointment of Ottone Visconti as archbishop of Milan in 1262. Pope Urban IV preferred Ottone to Raimondo, another candidate from the Della Torre family. Prevented from assuming his office and forced by the opposite faction to remain outside the city, Ottone settled in Arona, a town at the Milanese archdiocese's border. At the end of 1263, Della Torre forces, with the support of Oberto Pallavicino, dislodged him from Arona. Ottone sought refuge in central Italy near the pope.[29][27][30]

In 1264, Pallavicino left his office, leaving the Della Torre family members as the sole rulers of Milan. Under the guidance of Filippo Della Torre, brother of Martino and his successor after 1263, the Della Torre party took advantage of the favor of Charles of Anjou. Milan allied with him and other northern Italian cities (Guelph League) to fight the Hohenstaufen rule in southern Italy. Francesco Della Torre led the Milanese expedition, which ended in 1266 with the defeat of Manfred of Sicily, son of Frederick II, in the Battle of Benevento. Charles of Anjou became the new King of Sicily, having an indirect rule (exercised through the Della Torre) on Milan.[31][27][32]

In 1266, trying to take advantage of the favorable moment, the Della Torre advocated their cause against the Visconti in a consistory held by Pope Clement IV in Viterbo and attended by archbishop Ottone. Despite the presence of a delegate of Charles of Anjou, the pope's decision was in Ottone's favor. The pope then attempted to appease the two factions through an oath of allegiance demanded from the Milanese population. Part of it was the acceptance of Ottone as archbishop. However, new circumstances again changed the events in favor of Della Torre. At the end of 1266, the German princes decided to support Conradin, the last Hohenstaufen member, to recover the domains in southern Italy lost to the Anjou house after the defeat of Benevento. This move again reinstated Della Torre as leader of the Guelph League. Moreover, in 1268, Clement IV died, initiating a period of papal vacancy that left the dispositions in favor of Ottone without practical consequences.[33][34]

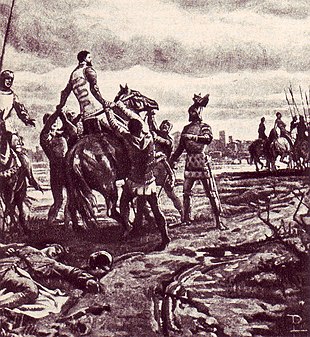

The defeat and execution of Conradin in Naples in 1268 meant the definitive end of the Hohenstaufen threat to Milan. Then, the confrontation between the two Milanese factions resumed and increasingly assumed a military connotation. A leading figure on the Visconti side was Simone Orelli da Locarno, whose military ability became legendary during the wars against Fredrick II. Notwithstanding this, being in favor of the Visconti, he was arrested in 1263 and jailed in Milan. In 1276, he was freed in the context of a compromise between the two factions about Como, and after he promised not to act against Della Torre. He joined the Visconti army altogether, assuming the role of General Captain. The Visconti forces gained ground in the Lake Maggiore's area, but in the same year, Tebaldo Visconti, nephew of Ottone, was captured with other leading figures. Brought to Gallarate, they were executed by beheading. The Visconti defeated the Della Torre army in the decisive Battle of Desio on 21 January 1277, opening the way for Ottone to enter Milan. Napoleone, son of Pagano, was arrested with other Della Torre family members. He died in jail a few months later. These events mark the foundation of the Visconti lordship of Milan.[33][35][36]

Ottone initially granted power in Milan to Simone Orelli, appointing him Captain of the People. In 1287, he transferred this role to his grandnephew Matteo Visconti (the son of Tebaldo executed in 1276). One year later, Matteo obtained the title of Imperial vicar from the emperor Rudolf of Habsburg. Ottone died in 1295, leaving Matteo as the new Lord of Milan. In 1302, the Della Torre retook power, forcing Matteo to leave the city. In 1311, Emperor Henry VII appeased the dispute between the two families and restored Matteo's lordship.[37][35][38] After him, seven members of his offspring, along four generations, ruled over Milan and a growing territory in northern and central Italy.

Rulers and their families

[edit]Matteo, Galeazzo, Azzone, Luchino, and Giovanni (1311–1354)

[edit]The reconciliation agreement with the Della Torre family, reached in December 1310 on the initiative of Henry VII, was attended by Matteo, his brother Uberto, and their cousin Ludovico, also known as Lodrisio.[39] Matteo acted alone as Lord of Milan in the following years. He ruled for about eleven years, providing to his family the legal basis for the hereditary lordship over Milan and extending the territory under the Milanese influence against the traditional opponents of the Visconti: the Della Torre and Anjou dynasties allied with the Papacy. After being accused of necromancy and heresy, he was convicted by the Church. Looking for a reconciliation, he transferred the power to his eldest son Galeazzo and left Milan for the Augustinian monastery of Crescenzago, where he died in 1322.[40][41]

After Matteo's death, Galeazzo associated his brothers, Marco, Luchino, Stefano, and Giovanni (a cleric), in the inherited domains' controls. He died five years later, succeeded by his son Azzone, who ruled between 1329 and 1339. Stefano married Valentina Doria from Genoa and died in 1327 under unclear circumstances. He left three sons: Matteo (Matteo II), Bernabò, and Galeazzo (Galeazzo II). Marco felt in disgrace and was killed by hitmen in 1329[42][43]

During Azzone's rule, Lodrisio (the cousin of Matteo, who in 1310 attended the reconciliation with the Della Torre) raised against him, trying to revert the line of succession in favor of his own family. He obtained the support of the Della Scala family of Verona. However, in the Battle of Parabiago, 1339, he was defeated by an army led by Azzone and backed by his uncles, Luchino and Giovanni. Azzone died in 1339 without sons, and the power passed to Luchino and Giovanni (since 1342, archbishop of Milan).[44][45] In the years of their rule, Matteo II, Bernabò, and Galeazzo II were suspected of conspiring against Luchino. Threatened by him, they left Milan.[46][47]

After Luchino died in 1349, archbishop Giovanni remained alone in power and recalled Matteo II, Bernabò, and Galeazzo II in Milan. Under his rule, the territorial expansion continued (to Genoa and Bologna) thanks to his diplomacy. Part of his initiatives were the marriages of his nephews to members of the nearby noble dynasties of northern Italy: in 1340, Matteo II to Egidiola Gonzaga; in 1350, Bernabò to Regina Della Scala and Galeazzo II to Bianca of Savoy.[48][49] In 1353, Petrarch accepted an invitation from Giovanni and moved to Milan, where he lived until 1361. He took part in Visconti's diplomatic initiatives and provided first-hand accounts of his life in Milan and Visconti's family events in his letters.[50][51]

Joint lordship of Matteo II, Bernabò, and Galeazzo II (1354–1385)

[edit]On 5 October 1354, archbishop Giovanni died. A few days later, Petrarch held a commemorative oration in his honor.[52] In the same month, Matteo II, Bernabò, and Galeazzo II agreed to share the power, dividing the Visconti domains according to geographic criteria. Matteo II died the following year, and Bernabò and Galeazzo II divided his territory between them. The two brothers settled their courts separately: Bernabò in Milan and Galeazzo II in Pavia.[53][54] Bernabò and Galeazzo II extended the Visconti relationships to several European noble dynasties through their children's marriages.

In 1360, Gian Galeazzo, son of Galeazzo II, married Isabelle of Valois, daughter of King John II of France.[55] The marriage was the result of negotiation, also participated by Petrarch with a journey to Paris,[56] leading the Visconti to contribute 600,000 francs to the ransom paid by France to England to obtain the freedom of the King in an episode of the Hundred Years' War.[57][58] Violante, daughter of Galeazzo II, married in 1368 Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence, the third son of King Edward III of England. After her husband's death, only a few months after the marriage, in 1377, Violante married Secondotto, Marquess of Montferrat. Again widowed, in 1381, she married her cousin Lodovico, one of the sons of Bernabò.[59][60][61]

Bernabò and his wife, Regina Della Scala, had 15 children. Nine daughters (Taddea, Viridis, Valentina, Agnese, Antonia, Maddalena, Anglesia, Elisabetta, Lucia) married scions of other European dynasties, connecting the Visconti to the houses of Wittelsbach (Taddea, Maddalena, Elisabetta), Habsburg (Viridis), Poitiers-Lusignan (Valentina, Anglesia), Württemberg (Antonia), Gonzaga (Agnese), Holland (Lucia). Their sons Marco and Carlo married Elisabeth of Bavaria and Beatrice of Armagnac, respectively. Caterina, another daughter of Bernabò, married in 1380 her cousin Gian Galeazzo, widow of Isabelle of Valois, who died in 1373 in Pavia while giving birth to her fourth child.[62][63]

When Galeazzo II died in 1378, his son Gian Galeazzo was the only heir of his half of the Visconti territories. Bernabò, 28 years older than his nephew, tended to assume a leading role towards him. The two Visconti had different personalities and ruling styles: instinctive, bad-tempered, and establisher of a terror regime, Bernabò; circumspect and relatively mild to his subjects, Gian Galeazzo. In the following years, the relationship between the two Visconti progressively deteriorated.[64][65]

A few months after the death of his wife and counselor, Bernabò was deposed by his nephew in a coup, probably prepared for years and kept secret. On 5 May 1385, accompanied by his generals (Jacopo dal Verme, Antonio Porro, and Guglielmo Bevilacqua) and with a heavily armed escort, Gian Galeazzo moved from Pavia for an apparent pilgrimage journey to Santa Maria del Monte di Velate near Varese. The following day, passing by Milan, he arranged to meet Bernabò for what was expected to be a familiar greeting. Bernabò, unprotected, was intercepted and arrested. The coup also led to the arrest of two sons of Bernabò, who were accompanying him. The people in the domains of Bernabò, firstly the Milanese, promptly submitted to Gian Galeazzo, an attitude widely attributed to their desire to abandon the ruthless regime under which they had been living. Incarcerated in his own castle at Trezzo sull'Adda, Bernabò died a few months later after being given a poisoned meal.[66][67][68]

Gian Galeazzo, sole ruler and Duke of Milan (1385–1402)

[edit]The death of Bernabò left Gian Galeazzo as the sole ruler of the Visconti territories. The two sons of Bernabò arrested with him (Ludovico and Rodolfo) spent the rest of their lives in jail. The two still free (Carlo and Mastino) lived far from Milan and never posed a threat to Gian Galeazzo. Only the Della Scala in Verona, their mother's family, continued to support them. After reaching some agreement with their cousin, they ended their lives in exile in Bavaria and Venice. The three unmarried daughters of Bernabò (Anglesia, Elisabetta, Lucia) moved to Pavia. They lived there under the care of their sister Caterina, the second wife of Gian Galeazzo, until their wedding.[69][70][71]

For his court, Gian Galeazzo preferred Pavia to Milan. There, he continued to develop the castle's renowned library and support the local university.[72][73] His daughter Valentina revived the relationship with the French royal family, interrupted by his first wife Isabelle's death. She married in 1389 Louis I, Duke of Orléans, brother of Charles VI, King of France. The three sons of Gian Galeazzo and Isabelle died before reaching adulthood.[74][75][76]

Gian Galeazzo and Caterina had two sons: Giovanni Maria in 1388 and Filippo Maria in 1392. In 1395, for 100,000 florins, Gian Galeazzo obtained the Duke of Milan's title from the King Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia. During his rule, the Visconti territories reached their broadest extension in northern and central Italy. Among the previous domains, only Genoa, ruled by archbishop Giovanni, remained excluded. After a short disease, the plague or gout, Gian Galeazzo died on 3 September 1402.[77][78][79]

Giovanni Maria and Filippo Maria (1402–1447)

[edit]The unexpected death of Gian Galeazzo caused severe difficulty for the Visconti court. The news of his end was initially kept secret, and the funeral was delayed until 20 October 1402. The two sons, only 12 and 10 years old, remained under the care of their mother, Caterina, who acted as Regent according to Gian Galeazzo's last will. A Council of Regency supporting Caterina was set up, but contrasts soon emerged inside it. Moreover, some members of Visconti's collateral branches and two of Bernabò's illegitimate sons opposed Caterina's regency, using circumstances to gain power. In 1404, Giovanni Maria became the new Duke of Milan. Ruling under the influence of his mother's opposers, he induced her to leave Milan for Monza. There, on 17 October 1404, she died in unclear circumstances.[80][81][82]

During the rule of Giovanni Maria, the political crisis deteriorated. Facino Cane, one of Gian Galeazzo's generals, obtained the title of Count of Biandrate and gained considerable authority in the Visconti territories. Other local forces emerged, leading to the fragmentation of territorial unity. Nearby powers conquered peripheral regions. This situation ended in 1412 when Facino Cane died, and a conspiracy against Giovanni Maria led to his assassination. In the same year, his brother Filippo Maria married the widow of Facino Cane, the 42-year-old Beatrice of Tenda, taking advantage of a testamentary disposition in favor of any Visconti that would have married her. The marriage ended with the accusation of adultery against Beatrice, her incarceration, and the sentence to death carried out in the Binasco castle in 1418.[83][84]

In 1428, Filippo Maria married Mary of Savoy, but they had no sons. In 1425, his mistress Agnese Del Maino gave birth to an illegitimate daughter, Bianca Maria. Considered by his father his only heir, she grew up with her mother in the Abbiategrasso and Cusago castles.[85][86] In 1432, Bianca Maria was betrothed to Francesco Sforza, a condottiero of Filippo Maria. In 1441 she married him, granting him the succession to the Duchy of Milan. A sign of their marriage is visible today in the twin churches of Santa Maria Incoronata in Milan.[87][88]

The heirs of Bianca Maria and Valentina, dukes of Milan (1450–1535)

[edit]After the death of Filippo Maria in 1447 and the short-lived Ambrosian Republic in 1447–1450, Francesco Sforza became the new Duke of Milan. Bianca Maria and her husband initiated a new dynasty that ruled Milan discontinuously until 1535.[89]

When Louis XII of France entered Milan in 1499 after the First Italian War, he leveraged a clause of the marriage contract of his grandmother Valentina, the daughter of Gian Galeazzo, to assume the title of Duke of Milan. After his death and the short rule of Maximilian Sforza (1512–1515), Francis I, heir of Valentina as well, inherited the Duchy. After an Imperial-Spanish army defeated France in the Battle of Pavia in 1525, a Sforza, Francesco II, assumed rule in Milan again. His death and a new war led the Duchy of Milan into the hands of Philip II of Spain, ending the line of succession initiated by Ottone and Matteo Visconti.[90][91]

Family tree

[edit]| Uberto Visconti [92][21] *? †1248 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Azzone[c] *? †? | Andreotto *? †? | Ottone[d] *1207 †1295 | Obizzo[e] *? †? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tebaldo *1230 †1276 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Matteo I[f] *1250 †1322 | Uberto *1280? †1315 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Galeazzo[g] *1277 †1328 | Marco *? †1329 | Luchino[h] *1287 †1349 | Stefano *1288 †1327 | Giovanni[i] *1290 †1354 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Azzone[j] *1302 †1339 | Luchino *? †1399 | Matteo II[k] *1319 †1355 | Galeazzo II[l] *1320? †1378 | Bernabò[m] *1323 †1385 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gian Galeazzo[n] *1351 †1402 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Louis I, Duke of Orléans *1372 †1407 | Valentina[o] *1371 †1408 | Giovanni Maria[p] *1388 †1412 | Filippo Maria[q] *1392 †1447 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| House of Valois-Orléans[r] | Bianca Maria[s] *1425 †1468 | Francesco Sforza *1401 †1466 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| House of Sforza[t] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Political developments and territorial hegemony of Milan

[edit]Under the rule of the Visconti, the government of the city of Milan underwent profound transformations while its territorial hegemony greatly extended, to suffer a crisis after the death of Gian Galeazzo.

The lordship of Ottone and Matteo brought to an end the confrontation between noble and popular parties, which had assumed growing violent forms in Milan during the 13th century. The new power of the Visconti initially relied on the combined roles of Archbishop (Ottone) and Captain of the People, along with the authority deriving from the title of Imperial Vicar (Matteo). After Matteo, the rule in the city assumed hereditary nature inside his family, making any formal recognition by the communal institutions unnecessary. The first Visconti claimed an absolute power (plenitudo potestatis) comparable to the one preserved to pope and emperor,[94][95] culminating with Bernabò, who openly considered their authorities irrelevant in his dominions.[96] The political change in Milan was part of the general decline of the Commune and the subsequent rise of the Signoria that affected northern and central Italy during 13th and 14th centuries.[97]

The annexation of the properties of the Milanese church, which included fortifications like the Angera and Arona castles guarding Lake Maggiore's navigation, was the first step Matteo Visconti took to consolidate his power in the territory of the Milanese diocese. That takeover originated a conflict with the Papacy that lasted the following decades.[98][99] The expansion of the Visconti rule outside the Milanese diocese took advantage of the traditional importance of Milan in northern Italy, reinforced by the leading role played in the Lombard League during the wars against the Hohenstaufen emperors.[100] After the destructions inflicted by Frederick Barbarossa in 1162, in a few years the Milanese reconstructed their city and defeated the emperor at Legnano in 1176, forcing him to the Peace of Constance, which granted autonomy also to the cities allied to Milan. The war was resumed against Frederick II and his successors, eventually leading to the end of the Hohenstaufen dynasty.[101][102] Based on this favorable position, after the death of Henry VII in 1313, Matteo and his son Galeazzo managed to become lords of other cities in northern Italy: Bergamo, Tortona, Alessandria, Vercelli, and Piacenza. Regimes favoring the Visconti settled in Como, Novara, and Pavia. During this first expansion phase, the Visconti continued to face the opposition of the Guelph League: the Papacy, the Anjou house (sovereigns in southern Italy), and the Della Torre family.[103][104]

After a crisis suffered during the years of Galeazzo I, the expansion continued under the lordship of Azzone with the military support of his uncle Luchino. In 1334 Cremona surrendered to Azzone. In 1337 Luchino entered Brescia, allowing Azzone to become Lord of the city. In 1339 Azzone and Luchino defeated in the Battle of Parabiago an army formed by their cousin Lodrisio Visconti and the Della Scala family, lords of Verona. In 1341, Luchino obtained a reconciliation with the Church. In 1346 Luchino took Parma, and in 1347 he extended the western border of the Visconti dominions along a stretch of land until Mondovì and Cuneo, at the foot of the Western Alps.[105][106][107]

After the death of Luchino, archbishop Giovanni further extended the territories under Milanese control. In 1350 he obtained Bologna from the Pepoli family, and in 1353 he accepted the lordship of Genoa. Through the marriages of his nephews (Matteo II, Bernabò, and Galeazzo II), he linked the Visconti dynastically to the families ruling the territories to the west and east of the Visconti dominions: the Gonzaga, the Della Scala, and the Savoy. The acquisition of Bologna, a city belonging to the territory of the Papal States, reopened the conflict with the pope. In 1352, negotiation with the papal envoy, the abbot Guillaume de Grimoard (later Pope Urban V), led to an agreement that allowed Giovanni to continue to rule Bologna as the papal vicar.[49][108][109][110]

Archbishop Giovanni's death in 1354 and the power transfer to Bernabò and Galeazzo II were followed by a reaction in Genoa and Bologna. In 1356 Genoa regained its independence. In Bologna, the rebellion of Giovanni Visconti di Oleggio, a former protégée of Archbishop Giovanni and his lieutenant in the city, opened the way to the intervention of Cardinal Albornoz, who in 1360 brought back the city within the Papal States. Bernabò, the ruler of the eastern portion of the Visconti dominions, repeatedly tried to recover Bologna. This, among other disputes with the Church, cost him a sentence of excommunication by Pope Innocent VI. After his defeat in the Battle of San Ruffillo in 1361, Bernabò finally came to terms with the loss of Bologna.[111][112] Bernabò and Galeazzo II engaged in bitter clashes also with the imperial authority. After the marquess of Monferrato was appointed imperial vicar in Pavia by Charles IV, the relationship between the emperor and the Visconti deteriorated. In November 1356, in the Battle of Casorate, Visconti forces under the command of Lodrisio Visconti (now reconciled with his cousins) defeated an imperial army and captured its commander, Marquard of Randeck. In 1359, Pavia surrendered to Galeazzo II.[113][114] His decision to erect a vast castle in Pavia for his family and court was a sign of his ambition to extend Visconti's dominions to the area of the ancient Lombard Kingdom.

In the 1370s, Bernabò and Galeazzo II emerged without severe consequences from manifold simultaneous attacks. The two brothers were deprived by the emperor of their vicariate and condemned by Pope Gregory XI as heretics. They subsequently suffered military incursions from the eastern border (by the count of Savoy) and from Bologna (by Papal-Florentine forces), which ended without significant impacts. Peace with the pope and reconciliation with the count of Savoy followed while Florence turned against the pope in a new war.[54][115] The extension of their matrimonial policies also marked Bernabò and Galeazzo II's years. The marriages of their daughters and sons connected the Visconti to the elite of the European aristocracy: the French and English royal houses and several German princely families.[116]

The ineffectiveness of the policies of both Empire and Papacy against the Visconti and the absence of internal conflicts that followed the arrest of Bernabò in 1385 encouraged Gian Galeazzo's expansion policy. Military and diplomatic initiatives were continuously taken and personally conducted by Gian Galeazzo from his castle in Pavia. A military campaign between 1386 and 1388 ended with the conquest of the Della Scala and Da Carrara territories of Verona and Padua.[117] Between 1390 and 1398, the attacks of Gian Galeazzo encountered the opposition of the local powers of northern and central Italy; wars against Florence and Mantua were ineffective and even led to the loss of Padua.[118] In 1399, without the use of force, Gian Galeazzo took possession of Pisa and Siena, followed by Perugia in 1400.[119] In July 1402, after the victory in the Battle of Casalecchio against a Bolognese-Florentine army, he assumed the rule of Bologna.[120] His sudden death in September 1402 prevented his long-foreseen attack on Florence.[121][122]

Gian Galeazzo accompanied the territorial expansion with reforms of the administration (creation of the Consiglio Segreto and the Consiglio di Giustizia), revenues (Maestri Delle Entrate) and criminal justice (Capitano di Giustizia). His promotion to the rank of Duke transformed Milan's territory (between Ticino and the Adda rivers) into a duchy.[123] The deep crisis that resulted after the death of Gian Galeazzo is attributed to the lack of time required to secure power in the rapidly growing dominions.[99] The territorial unity of the Visconti state was heavily affected, and the Council of Regency, created to overcome the young age of Gian Galeazzo's sons, could not stem the dividing forces that resurfaced, causing the collapse of the system of government built by him.[124][125] Filippo Maria restored the basis of the Visconti state, and the marriage of his daughter Bianca Maria to Francesco Sforza paved the way to a renewed strong government.[126] In the course of the 15th century, however, the territory under Milanese control narrowed to the Duchy of Milan and later never regained the extension reached under the Visconti rule.[127] In the 16th century, the absolute power established by the Visconti ended with Francesco II, the last Sforza duke.[128]

Cadet branches

[edit]Family branches have been continually arising since the appearance in Milan of the surname Visconti in the year 1075.[129]

During the first generations, the firstborn among brothers is supposed to have received the role of the most distinguished member of the house. The family of Archbishop Ottone and his grandnephew Matteo, first lords of Milan in the second half of the 13th century, are accordingly considered the descendants of the first Ariprando Visconti along an agnatic primogeniture line over about two centuries.[130] The younger brothers gave origin to cadet branches that continued to live in Milan, participating in the political life of the Milanese Commune.[131]

Vergante branches (since the 12th century)

[edit]In 1134, Guido Visconti (one of the members of the primogeniture line) obtained from the abbot of Saint Gall the castle of Massino located in the Vergante region on the hills overlooking Lake Maggiore.[132]

The firstborn of Guido Visconti, Ottone, is attested in Milan in the second half of the 12th century with prominent roles in the public life of the Milanese commune. His other descendants initiated to live in the Vergante, originating the cadet branches of the Visconti di Massino, the Visconti di Invorio, and the Visconti di Oleggio Castello.[133] To the Visconti di Massino belonged Uberto Pico, who happened to be confused with Uberto Visconti, the brother of Matteo Lord of Milan.[134] Member of the Visconti di Oleggio Castello was Giovanni, Lord of Bologna (1355–1360) and Fermo. He had been wrongly considered an illegitimate son of Archbishop Giovanni Visconti.[135]

Descendants of Pietro (since the 13th century)

[edit]From Ottone, son of Guido Visconti, descended the family of Archbishop Ottone and his nephew Tebaldo, executed in 1276 by the opposite faction supporting the Della Torre family.[136] After the death of Tebaldo, a division of the family inheritance occurred in 1288 between his sons (Matteo and Uberto) and Pietro (another nephew of Archbishop Ottone). The object of the division was the lands and castles between Lake Maggiore and Gallarate (a long-established area of Visconti possessions), the family compound in the center of Milan, and other properties. To Pietro went the territories near Gallarate, fortified with castles scattered on the local hills, to Matteo and Uberto the remaining parts.[137]

Among the descendants of Pietro, other divisions followed: first between his sons, Lodrisio and Gaspare, and a generation later among his grandchildren. The members of their offspring added the names of the inherited lands to their surnames. From the sons of Lodrisio (Ambrogio, Estorolo) originated the Visconti di Crenna and the Visconti di Besnate; from the sons of Gaspare (Azzo, Antonio, and Giovanni), the Visconti di Jerago, the Visconti di Orago, and the Visconti di Fontaneto. These branches became extinct in the following centuries, and their castles and lands passed to other families.[138]

Descendants of Uberto, brother of Matteo (since the 14th century)

[edit]A generation after separating the lands assigned to Pietro, another hereditary division followed between Matteo and Uberto, sons of Tebaldo. Matteo became Lord of Milan, while Uberto (c. 1280–1315) received the castles of Cislago and Somma Lombardo with the lands subject to them and originated other cadet branches.[139] Vercellino, the firstborn of Uberto, was Podestà of Vercelli (1317) and Novara (1318–1320).

From Vercellino, in the 15th century, descended Giambattista Visconti.[140] In 1473, after his death, the castle of Somma Lombardo was divided between his sons, Francesco and Guido.[141] The offspring of Francesco and Guido became known by the surname of Visconti di Somma. Several branches originated from them: among the descendants of Francesco, the Visconti di San Vito and the Visconti della Motta;[140] from Guido, the Visconti di Modrone and the Visconti di Cislago.[142]

Visconti di San Vito

[edit]A descendant of Francesco Visconti di Somma in the 17th century was Francesco Maria. In 1629, he received the title of Marquess of San Vito from the King of Spain. From him originated the Visconti di San Vito branch.[140]

Between the 19th and 20th centuries, the Visconti di San Vito reunited the property of the castle of Somma Lombardo, fragmented after the division of 1473. The Visconti di San Vito became extinct in 1998. Their last member left the tenure of Somma Lombardo to a foundation bearing their name, which later opened the castle to the public.[143]

Visconti di Modrone

[edit]From the descendants of Guido Visconti di Somma came the lateral branch of the Visconti di Modrone (marquesses of Vimodrone since 1694, later Dukes of Vimodrone since 1813).[142] To this family belonged the film directors Luchino Visconti di Modrone and Eriprando Visconti di Modrone. Luchino was one of the most prominent directors of Italian neorealist cinema.

Other members

[edit]- Federico Visconti (1617–1693), Cardinal and Archbishop of Milan from 1681 to 1693.

- Filippo Maria Visconti (archbishop) (1721–1801), Archbishop of Milan from 1784 to 1801.

- Gaspare Visconti, Archbishop of Milan from 1584 to 1595.

- Roberto Visconti, Archbishop of Milan from 1354 to 1361.

Builders and patrons of art and letters

[edit]In the territories of their initial power and later expansion, the Visconti promoted the construction of secular and religious buildings. The magnificence of their most distinctive projects, conceived in the 14th century mainly for Milan and Pavia, reflected their policy of authority assertion over the regions under their rule.[144][145]

Patronage of arts and letters was a noticeable trait within the Visconti house.[146] In the 14th century, the many family connections created by their marriage policies put the Visconti in a central position among the European aristocracy,[116] which made, according to the art historian Serena Romano, the Milan of the Visconti, and later of the Sforza, “unrivaled in Europe as an artistic crossroad.”[147]

Policy of magnificence in the 14th century

[edit]Azzone, Lord of Milan between 1329 and 1339, was the first Visconti to carry out an imposing building program to promote his seigniorial authority.[148][149] He intervened in the city's center in continuity with the urbanism of the Milanese commune, transforming the Broletto Vecchio (the center of the communal rule) into the Corte d'Arengo (today's Palazzo Reale), the seat of his government.[150] Near the Milan Cathedral, at the time Santa Maria Maggiore church, Azzone erected a bell tower taller than any other building in the territories under his rule, even surpassing Cremona's Torrazzo.[151] The bell tower collapsed in 1353 and was never rebuilt.[152] In 1335, Azzone called Giotto in Milan to decorate the Corte d'Arengo. A fresco, today lost, representing the Worldly Glory and Azzone himself among the greatest rulers of the past, has been attributed to him.[153][154]

Azzone's policy of magnificence was continued by his successors Luchino and Giovanni[155] and expanded in the second half of the 14th century by Galeazzo II, Bernabò, and Gian Galeazzo to a grandiosity level recognized in Europe.[156] Near the Corte d'Arengo, Giovanni built the new episcopal palace.[157] Luchino connected the Corte d'Arengo to the nearby Visconti's private buildings by galleried walkways and bridges overpassing public streets.[148] Between 1360 and 1365, Galeazzo II built a vast and widely decorated castle in Pavia, from where he and his son Gian Galeazzo ruled over their territories. According to Petrarch, who visited Pavia in 1365 and mentioned the castle in a letter addressed to Boccaccio, it was an "enormous palace," and it would have been judged, by Boccaccio himself, "the most majestic of all modern creations."[158][159] Around 1370, Bernabò erected a castle at Trezzo sull'Adda in a few years, including a massive 42-meter-high tower and a fortified bridge over the Adda River.[160] The bridge had a single arch 72 meters wide, a span never reached before and unsurpassed by a masonry structure until the 20th century.

In 1386, on the first anniversary of his ascent to power as sole ruler, Gian Galeazzo initiated the new Milan Cathedral, intended to be the largest church of Christendom. The ducal symbol of the radiant sun (Razza Viscontea) was chosen to decorate the main stained window of the central apse.[161][162] Ten years later, Gian Galeazzo founded the Charterhouse of Pavia to host his family's mausoleum. For its considerable dimensions and lavish decorations, it is today considered one of the most notable monuments in Italy. Gian Galeazzo connected the Pavia castle to the Charterhouse, located about 7 km north, by a large, enclosed park initiated by his father.[163] The opulence of the Pavia Charterhouse, built and decorated entirely of white marble, struck Erasmus of Rotterdam, who considered it excessive for a monastery.[164]

Builders

[edit]Commissioning of private and public buildings (mainly castles and churches) was frequent among the Visconti branches and widespread in the territories under their rule.

Castles, palaces, public buildings

[edit]The Visconti marked the territories of their origins and expansion with fortifications and palaces. Castles named after them (Castelli Viscontei in Italian) are frequent in Lombardy and Northern Italy.

The area northwest of Milan and east of Lake Maggiore, traditionally inhabited by the Visconti, is marked by castles at Besnate, Crenna, Jerago, Orago, and Somma Lombardo. In the Visconti territories on the western side of Lake Maggiore, family branches adapted existing fortifications or erected new castles in Castelletto sopra Ticino, Invorio, Massino, and Oleggio Castello.[165][166] In Milan, during the 14th and 15th centuries, the Visconti built the Castle of Porta Giovia on the site of a previous fortification. Destroyed after the end of the Visconti rule in the period of the Ambrosian Republic, it was rebuilt by Francesco Sforza. Continuously transformed over the centuries, it is today the Sforza Castle.[167][168] To locally mark their power, the Visconti erected fortifications in the territories where they extended their dominion (Bellinzona, Bergamo, Cassano d'Adda, Castell'Arquato, Cherasco, Galliate, Lecco, Legnano, Locarno, Lodi, Monza, Novara, Piacenza, Vercelli, Voghera, Vogogna). Other castles were built near Milan and used by family members as secondary residences (Abbiategrasso, Bereguardo, Cusago, Pandino, Vigevano).[169][170]

After the extinction of the lineage ruling Milan, cadet branches continued to erect or transform castles and palaces in Milan and Lombardy, and today, many locations host buildings named from them: Cislago, Brignano Gera d'Adda, Fagnano Olona, Saronno, and Milan (Palazzo Visconti di Grazzano, Palazzo Prospero Visconti).

The need to connect the Visconti territories led to the construction of fortified bridges, in Lecco and Trezzo sull'Adda.[171] Two ambitious programs to divert the waters of rivers flowing toward enemy cities, Mantova e Padova, prompted Gian Galeazzo to build two dams at Valeggio sul Mincio and Bassano del Grappa.[172]

In 1457, Bianca Maria Visconti and her husband Francesco Sforza donated the site of a previous Visconti stronghold in the center of Milan to fund the Ca' Granda, the new and vast city hospital. After Filarete's project, its construction continued over the following centuries, financed exclusively by private donations.[173]

Churches and monasteries

[edit]The Visconti's power over Milan was rooted in their family compound in the city center near the Corte d'Arengo, where the churches of San Gottardo in Corte and San Giovanni in Conca were the first examples of their palatine chapels. The second was transformed into the private church of Bernabò's family.[174] The Visconti added a chapel to the church of Sant'Eustorgio, serving as their family burial site.[175]

Visconti's coat of arms, the Biscione, marked the façade of minor Milanese churches under their patronage, making them recognizable today (San Cristoforo, Santa Maria Incoronata).[176] Regina Della Scala, the wife of Bernabò, erected the Santa Maria della Scala church, named after her surname. It was demolished in the 18th century to make way for the construction of a new theatre, which kept again her surname. The Visconti favored the Carthusian order. The grandiose Pavia Charterhouse was preceded by the Garegnano Charterhouse, founded by archbishop Giovanni Visconti in 1349.

The Visconti used the churches they built in Milan and Pavia as burial places: Ottone and Giovanni in the Cathedral, Azzone in San Gottardo in Corte, Stefano in Sant'Eustorgio, Bernabò in San Giovanni in Conca and Gian Galeazzo in the Pavia Charterhouse.[177]

Patrons of art and letters

[edit]In Lombardy

[edit]Since the first years of their rule of Milan, the Visconti patronized art and letters, on several occasions to celebrate their members' achievements.

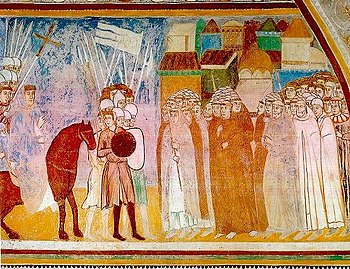

A poem written by the contemporary Dominican Stefanardo da Vimercate (Liber de gestis in civitate Mediolani) told the story of archbishop Ottone Visconti, culminating with his victory over the Della Torre in 1277. A few years later, probably before the end of the 13th century, an anonymous painter (known as Maestro di Angera) frescoed the main events of that story on the wall of the Sala di Giustizia (Hall of Justice) in the Angera castle.[178][179] Giotto's stay in Milan and his work in the Corte d'Arengo, commissioned by Azzone Visconti, marked a turning point in Lombard painting and inspired local artists who worked in other Visconti buildings. The nearby Archbishop's palace, under Giovanni Visconti, and San Giovanni in Conca church, under Bernabò Visconti, were extensively decorated with frescoes. Today, only a few fragments survive.[180]

After exchanging letters with Luchino Visconti in 1353, Petrarch accepted, despite the opposition of his friend Boccaccio, the invitation of Archbishop Giovanni Visconti and spent the following eight years in Milan.[181][182] He remained a friend of Galeazzo II and returned to Pavia and Milan on several occasions.[183]

The numerous rooms of the Pavia Castle were painted with decorative frescoes. Due to the vastness of the walls to be decorated and needing more painters, Galeazzo II requested the Gonzagas of Mantua to send all the artists available there to Pavia.[184][158] In the castle of Pavia, on the first floor of the western tower, Galeazzo II Visconti set up a vast library. It contained about one thousand books by classical and contemporary authors and was renowned in Europe.[185] Under the patronage of the Visconti, Pavia University became one of the most esteemed in Europe. To help the students attend the university, Galeazzo II supported them with endowments.[186]

The Visconti commissioned statues and funeral monuments to prominent sculptors. Giovanni di Balduccio made the funeral monument of Azzone Visconti in the San Gottardo in Corte church.[188] Bonino da Campione sculpted an equestrian statue of Bernabò, which was later placed on his sarcophagus in the San Giovanni in Conca church and decorated the tomb of his wife Regina della Scala; they are today preserved in the Sforza castle museum (Museo d'Arte Antica). Bianca Maria Visconti and her husband, Francesco Sforza, favored the portraiture of Bonifacio Bembo, who was granted Milanese citizenship.[189][190]

The outstanding marble construction effort and the sculptural decorations characterizing the religious buildings initiated by Gian Galeazzo (Milan Cathedral and Pavia Charterhouse) continued in the following centuries. The first sculptors to work there during Visconti's rule were Giovannino de' Grassi and Giacomo da Campione.[191][192] The painter Michelino da Besozzo worked on the Cathedral stained glass.[193]

Influences in Europe

[edit]The many relationships established by the Visconti with other European ruling families contributed to spreading the incipient Renaissance humanism outside Italy.

During his stay in Milan, the Visconti sent Petrarch on two missions to Europe.[194] In 1356, he went to Prague, where he met Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor.[195] In 1361, Galeazzo II sent Petrarch to Paris to congratulate King John II for his release after the English captivity. As a gift, he brought a ring lost by the King in the battle of Poitiers and recovered by Galeazzo II. His oration to the King praised his daughter, Isabella, now living in Pavia as Gian Galeazzo's wife, and talked about the Fortuna.[196] The impression he made on the courts of Prague and Paris led the emperor and the French royal family to invite Petrarch to stay by them, but, in both cases, he preferred to return to Milan.[197] Petrarch's book De remediis utriusque fortune, conceived under the influence of Milanese literary culture, had great resonance in Europe.[198][199]

In 1368, the marriage ceremony of Violante Visconti to the son of the King of England and the subsequent nuptial banquet was attended by Petrarch, Jean Froissart, who had accompanied the bridegroom in his journey to Italy, and maybe Geoffrey Chaucer.[200][201] Later, in 1372/1373 and 1378, Chaucer traveled to Milan and Pavia, where he had access to the Visconti libraries and met Petrarch. These two circumstances played a role in Italian humanism's influence on him.[202][201] The marriages of five daughters of Bernabò to German and Austrian princes (Antonia in Württemberg; Taddea, Maddalena, and Elisabetta in Bavaria; Viridis in Austria) are credited to have contributed to a culture transfer to the regions ruled by their husbands.[203] The marriage of Valentina to Louis I, Duke of Orléans, in 1389 influenced literary and artistic developments in France.[204]

The construction site of the new cathedral attracted architects, engineers, and sculptors from France and Germany (Nicolas de Bonaventure, Jacques Coene, Ulrich von Ensingen, Hans von Fernach, Heinrich Parler von Gmünd, Jean Mignot, Peter Monich, Walter Monich), who interacted with the Italian ones. As a result, Milan Cathedral became symbolic of the International Lombard Gothic style.[205][206][207]

During the Italian wars, the Visconti Library in Pavia, rich in 1,000 manuscripts, raised the interest of Louis XII, King of France, who transferred most of them to Blois, France. Today, they are preserved in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.[208]

Portrayal in pop culture

[edit]In Thomas Harris's 1999 novel Hannibal, the serial killer Hannibal Lecter is a member of the Visconti family, descended from them through his mother Simonetta. The Visconti family crest is used as the cover of the book.

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Otto autem Mediolanensis vicecomes cum multis pugnatoribus eiusdem regis in ipsa strage coruit in mortem, amarissimam hominibus diligentibus civitatem Mediolanensium et ecclesiam."[5]

- ^ "Hoc ubi Otto comes Mediolanensis perspexit, pro imperatore se ad mortem obiciens, equum suum contradidit; nec mora, a Romanis captus, et in Urbem inductus, minutatim concisus est, eiusque carnes in platea canibus devorandae relictae."[6]

- ^ Bishop of Ventimiglia (1251 - 1262).

- ^ Archbishop of Milan (1262), lord of Milan (1277-78) and (1282-85).

- ^ Console di giustizia in Milan (1236)).

- ^ Capitano del popolo of Milan (1287–1298), lord of Milan (1287–1302, 1311–1322).[93]

- ^ Lord of Milan (1322–1327).[93]

- ^ Lord of Milan (1339–1349).[93]

- ^ Archbishop of Milan (1339), lord of Milan (1339–1354),[93] lord of Bologna and Genoa (1331–1354).

- ^ Lord of Milan (1329–1339).[93]

- ^ Lord of Milan (1354–1355).[93]

- ^ Lord of Milan (1354–1378).[93]

- ^ Lord of Milan (1354–1385).[93]

- ^ Lord of Milan (1378–1395) and Duke of Milan (1395–1402).[93]

- ^ By the first wife, Isabelle of Valois; grandmother of Louis XII of France, who conquered Milan as her heir.

- ^ By the second wife, Caterina Visconti; duke of Milan (1402–1412).[93]

- ^ By the second wife, Caterina Visconti; duke of Milan (1412–1447).[93]

- ^ Dukes of Milan: Louis XII (1499–1500, 1500–1512), Francis I (1515–1521).[93]

- ^ Illegitimate, by Agnese del Maino; in 1441 married to Francesco I Sforza, later duke of Milan.

- ^ Dukes of Milan: Francesco I (1450–1466), Galeazzo Maria (1466–1476), Giangaleazzo (1466–1476), Ludovico il Moro (1494–1499, 1500), Massimiliano (1512–1515), Francesco II (1521–1535).[93]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Hale (1981), pp. 338–339, 351.

- ^ Vittani & Manaresi (1969), docc. 557–560.

- ^ Biscaro (1911), pp. 20–24.

- ^ Filippini (2014), pp. 33–42.

- ^ Bethmann & Jaffé (1868), p. 31, rr. 33-35.

- ^ Wattenbach (1846), p. 780, rr. 37–40.

- ^ Filippini (2014), pp. 44–45, 83.

- ^ Filippini (2014), pp. 85–90.

- ^ Keller (1979), p. 207.

- ^ Filippini (2014), pp. 90–98.

- ^ Keller (1979), pp. 206–207, 364–365.

- ^ Hausmann (1969), doc. 21.

- ^ Filippini (2014), p. 61.

- ^ Filippini (2014), pp. 58–65.

- ^ Hausmann (1969), doc. 20.

- ^ Biscaro (1911), p. 28.

- ^ Filippini (2014), pp. 73–74.

- ^ Filippini (2014), pp. 100–101.

- ^ Morena & Morena (1994), p. 152.

- ^ Filippini (2014), pp. 105–113.

- ^ a b Visconti (1967), p. 275.

- ^ Filippini (2014), pp. 62–63.

- ^ Hale (1981), pp. 338–341, 352.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 33–45.

- ^ Menant (2005), p. 67.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 45–51.

- ^ a b c Menant (2005), pp. 111–112.

- ^ Jones (1997), p. 520.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 52–57.

- ^ Jones (1997), p. 551.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 58–62.

- ^ Jones (1997), pp. 345–347.

- ^ a b Cognasso (2016), pp. 64–67.

- ^ Menant (2005), pp. 96–97.

- ^ a b Menant (2005), pp. 117–118.

- ^ Jones (1997), pp. 551, 619.

- ^ Muir (1924), pp. 10–13.

- ^ Jones (1997), p. 619.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 109–114.

- ^ Muir (1924), pp. 14–24.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 125–131, 142–146, 152.

- ^ Muir (1924), pp. 25–35.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 152–154, 163–164, 173–174.

- ^ Muir (1924), pp. 34, 36.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 189–191.

- ^ Muir (1924), pp. 37–38.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 189–190, 191–192, 207–210.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 208, 210–213.

- ^ a b Bueno de Mesquita (1941), pp. 6–7.

- ^ Muir (1924), pp. 39–40.

- ^ Wilkins (1958).

- ^ Wilkins (1958), pp. 75–76.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 208, 235–236, 240.

- ^ a b Bueno de Mesquita (1941), pp. 8–9.

- ^ Muir (1924), pp. 61–62.

- ^ Wilkins (1958), pp. 219–225.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 208, 255–256.

- ^ Bueno de Mesquita (1941), p. 10.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 256, 263.

- ^ Bueno de Mesquita (1941), pp. 12–13.

- ^ Muir (1924), pp. 63–65, 83.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 292–293, 283–284, 333–334.

- ^ Muir (1924), pp. 82–83.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 284–285.

- ^ Bueno de Mesquita (1941), pp. 13–14.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 289–302.

- ^ Bueno de Mesquita (1941), pp. 31–34.

- ^ Muir (1924), pp. 85–87.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 333–334, 338.

- ^ Bueno de Mesquita (1941), pp. 144, 171.

- ^ Muir (1924), pp. 91–92, 204.

- ^ Bueno de Mesquita (1941), pp. 41–42.

- ^ Muir (1924), pp. 233–234.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 325–326, 368–371.

- ^ Bueno de Mesquita (1941), pp. 63–68, 79–80, 105.

- ^ Muir (1924), pp. 94–95.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 319–323, 379–380.

- ^ Bueno de Mesquita (1941), pp. 173–175, 297–298.

- ^ Muir (1924), pp. 101–119.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 379–395.

- ^ Bueno de Mesquita (1941), pp. 298–301.

- ^ Muir (1924), pp. 119–120, 125–130.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 415–416.

- ^ Muir (1924), pp. 136, 139–140.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 452–453, 457.

- ^ Muir (1924), pp. 135, 147.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 457, 484–486.

- ^ Muir (1924), pp. 163–164.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 528–540, 541–547.

- ^ Black (2009), pp. 182–184.

- ^ Gamberini (2014), pp. 36–37.

- ^ Hale (1981), p. 339.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Black (2009), p. xiii.

- ^ Black (2009), pp. 38–56.

- ^ Gamberini (2014), pp. 21–23.

- ^ Black (2009), pp. 52–53.

- ^ Jones (1997), pp. 152–650.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), p. 132.

- ^ a b Gamberini (2014), p. 24.

- ^ Gamberini (2014), pp. 19–20.

- ^ Jones (1997), pp. 335–358.

- ^ Menant (2005), pp. 17–22, 47–52.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 132–168.

- ^ Gamberini (2014), pp. 28–29.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 191–205.

- ^ Black (2009), pp. 38–42.

- ^ Gamberini (2014), p. 39.

- ^ Black (2009), pp. 42–43.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 207–234.

- ^ Gamberini (2014), p. 30.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 239–240, 248–253.

- ^ Black (2009), pp. 51–52.

- ^ Bueno de Mesquita (1941), pp. 7–8.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), pp. 241–244.

- ^ Black (2009), pp. 52–54.

- ^ a b Gamberini (2014), pp. 30–31.

- ^ Bueno de Mesquita (1941), pp. 69–83.

- ^ Bueno de Mesquita (1941), pp. 121–136, 206–223.

- ^ Bueno de Mesquita (1941), pp. 239–258.

- ^ Bueno de Mesquita (1941), pp. 272–280.

- ^ Bueno de Mesquita (1941), pp. 281–301, 305.

- ^ Gamberini (2014), p. 31.

- ^ Black (2009), pp. 68–72.

- ^ Bueno de Mesquita (1941), pp. 301–304.

- ^ Black (2009), pp. 72–73.

- ^ Black (2009), pp. 73–93.

- ^ Gamberini (2014), pp. 34–37.

- ^ Black (2009), pp. 182–198.

- ^ Litta Biumi (1819–1884).

- ^ Filippini (2014), pp. 83–85, 187.

- ^ Filippini (2014), pp. 98–104, 187.

- ^ Filippini (2014), pp. 58–61.

- ^ Filippini (2014), pp. 61–65, 98–101.

- ^ Filippini (2014), p. 17.

- ^ Muir (1924), pp. 49–51.

- ^ Cognasso (2016), p. 71.

- ^ Litta Biumi (1819–1884), tavola X.

- ^ Litta Biumi (1819–1884), tavola X–XI.

- ^ Litta Biumi (1819–1884), tavola XIV.

- ^ a b c Litta Biumi (1819–1884), tavola XVI.

- ^ Grisoni & Bertacchi (2014), p. 56.

- ^ a b Litta Biumi (1819–1884), tavola XVII.

- ^ Grisoni & Bertacchi (2014), pp. 62–63.

- ^ Welch (1995), pp. 169–175.

- ^ Boucheron (1998), pp. 617–619.

- ^ Muir (1924), p. 222.

- ^ Romano (2014), p. 214.

- ^ a b Welch (1995), p. 173.

- ^ Boucheron (1998), p. 618.

- ^ Boucheron (1998), p. 117.

- ^ Boucheron (1998), p. 122.

- ^ Boucheron (1998), p. 156.

- ^ Boucheron (1998), pp. 119–121.

- ^ Romano (2014), pp. 217–218.

- ^ Welch (1995), pp. 171–173.

- ^ Muir (1924), p. 52.

- ^ Welch (1995), p. 171.

- ^ a b Welch (1989), p. 353.

- ^ Welch (1995), p. 175.

- ^ Vincenti (1981), pp. 70–74.

- ^ Welch (1995), pp. 49–56.

- ^ Boucheron (1998), p. 191.

- ^ Muir (1924), pp. 239–245.

- ^ Boucheron (1998), pp. 442–443.

- ^ Vincenti (1981), p. 18.

- ^ Del Tredici & Rossetti (2012), pp. 88–127.

- ^ Welch (1995), pp. 175–176.

- ^ Del Tredici & Rossetti (2012), pp. 26–37.

- ^ Vincenti (1981), pp. 14–17.

- ^ Del Tredici & Rossetti (2012), pp. 38–53, 72–78.

- ^ Vincenti (1981), pp. 92–100.

- ^ Vincenti (1981), pp. 92–95.

- ^ Welch (1995), pp. 120–124.

- ^ Romano (2014), pp. 217, 221.

- ^ Romano (2014), p. 216.

- ^ Boucheron (1998), pp. 131–138.

- ^ Muir (1924), p. 246.

- ^ Welch (1995), pp. 12–16.

- ^ Romano (2014), p. 215.

- ^ Romano (2014), pp. 219–220.

- ^ Muir (1924), pp. 222–228.

- ^ Wilkins (1958), pp. 16–244.

- ^ Wilkins (1958), pp. 247–248.

- ^ Muir (1924), p. 198.

- ^ Muir (1924), pp. 90, 198–199.

- ^ Muir (1924), pp. 231–233.

- ^ Welch (1989), pp. 359–360.

- ^ Boucheron (1998), p. 124.

- ^ Welch (1995), p. 247.

- ^ Boucheron (1998), p. 337.

- ^ Boucheron (1998), pp. 71–104.

- ^ Romano (2014), pp. 223–225.

- ^ Romano (2014), p. 226.

- ^ Muir (1924), p. 225.

- ^ Wilkins (1958), pp. 122–124.

- ^ Wilkins (1958), pp. 219–224.

- ^ Wilkins (1958), pp. 225–227.

- ^ Rückert (2008), p. 14.

- ^ Grote (2008).

- ^ Cook (1916), p. 74–85.

- ^ a b Rossiter (2010), p. 38.

- ^ Coleman (1982).

- ^ Rückert (2008), pp. 30–31.

- ^ Collas (1911), pp. 121–139.

- ^ Welch (1995), pp. 83–114.

- ^ Boucheron (1998), pp. 165–177.

- ^ Romano (2014), pp. 223–226.

- ^ Gagné (2021), p. 156.

Primary sources

[edit]- Vittani, Giovanni; Manaresi, Cesare, eds. (1969) [1933]. Gli atti privati milanesi e comaschi del sec. XI [The private acts of the Milanese and the Como in the 11th century]. Bibliotheca historica italica (in Italian and Latin). Vol. 6. Milano: Castello Sforzesco. OCLC 63137745.

- Bethmann, Ludwig; Jaffé, Philipp, eds. (1868). Landulfi de Sancto Paolo Historia Mediolanensis [Landulf of Saint Paul's 'History of Milan']. Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores (in folio) (in Latin). Vol. 20. Hannover: MGH. pp. 17–49.

- Wattenbach, Wilhelm, ed. (1846). Leonis Marsicani et Petri Diaconi Chronica Monasterii Casinensis [Leo Marsicanus and Peter the Deacon's 'Montecassino Chronicle']. Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores (in folio) (in Latin). Vol. 7. Hannover: MGH. pp. 727–844.

- Hausmann, Friedrich, ed. (1969). Die Urkunden Konrads III. und seines Sohnes Heinrich [The documents of Conrad III and his son Henry]. Monumenta Germaniae historica (in German and Latin). Wien, Köln, Graz: H. Böhlaus Nachf. OCLC 1081868191.

- Morena, Otto; Morena, Acerbo (1994) [1930]. Güterbock, Ferdinand (ed.). Das geschichtswerk des Otto Morena und seiner fortsetzer über die taten Friedrichs I, in der Lombardei [The historical work of Otto Morena and his son on the deeds of Frederick I in Lombardy] (in German and Latin). Munchen: Monumenta Germaniae Historica. ISBN 9783921575369. OCLC 43984534, 824246002. Retrieved 2019-05-15.

Secondary sources

[edit]- Biscaro, Gerolamo (1911). "I maggiori dei Visconti, signori di Milano" (PDF). Archivio Storico Lombardo (in Italian). 38: 5–76. Retrieved July 12, 2024.

- Black, Jane (2009). Absolutism in Renaissance Milan. Plenitude of power under the Visconti and the Sforza 1329–1535. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199565290. OCLC 1007134403.

- Boucheron, Patrick (1998). Le pouvoir de bâtir: urbanisme et politique édilitaire à Milan (XIVe - XVe siècles) (in French). Rome: École française de Rome. ISBN 9782728305247. OCLC 246472536.

- Bueno de Mesquita, Daniel Meredith (1941). Giangaleazzo Visconti, Duke of Milan (1351–1402): a study in the political career of an Italian despot. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521234559. OCLC 749858378.

- Cognasso, Francesco (2016). I Visconti. Storia di una famiglia (in Italian) (2nd ed.). Bologna: Odaya. ISBN 9788862883061. OCLC 982263664.

- Coleman, William E. (1982). "Chaucer, the Teseida, and the Visconti library at Pavia: a hypotesis". Medium Ævum. 51 (1): 92–101. doi:10.2307/43632126.

- Collas, Émile (1911). Valentine de Milan, Duchesse d’Orléans (in French). Paris: Librairie Plon. OCLC 10844490.

- Cook, Albert Stanburrough (1916). The last months of Chaucer's early patron. Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Artes and Sciences. Vol. 21. New Haven, Connecticut. OCLC 559009246. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Del Tredici, Federico; Rossetti, Edoardo (2012). Castle trails from Milan to Bellinzona - Guide to the dukedom's castles. Milan: Nexi-Castelli del ducato. ISBN 9788896451069. OCLC 955635027. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- Filippini, Ambrogio (2014). I Visconti di Milano nei secoli XI e XII. Indagini tra le fonti (in Italian). Trento: Tangram Edizioni Scientifiche. ISBN 9788864580968. OCLC 887857144.

- Gagné, John (2021). Milan Undone. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674249936. OCLC 1232237123.

- Gamberini, Andrea (2014). "Milan and Lombardy in the era of the Visconti and the Sforza". In Gamberini, Andrea (ed.). A companion to late medieval and early modern Milan. The distinctive features of an Italian state. Leiden & Boston: Brill. pp. 19–45. ISBN 9789004284128.

- Grisoni, Michela M.; Bertacchi, Cristina (2014). "Three castles in one: Castello Visconti di San Vito, Somma Lombardo (Varese)". In Villoresi, Valerio (ed.). Lombard villas and stately homes. Turin: AdArte. pp. 56–71. ISBN 9788889082546. OCLC 896832706.

- Grote, Hans (2008). "Francesco Petrarca und die literarische Kultur in Mailand der Visconti: Zür Entstehungskontext". In Rückert, Peter; Sönke, Lorenz (eds.). Die Visconti und der deutsche Südwesten. Kulturtransfer im Spätmittelalter (in German). Ostfildern: Jan Thorbeck Verlag. pp. 237–252. ISBN 9783799555111. OCLC 298988901.

- Hale, John Rigby (1981). A concise encyclopaedia of the Italian Renaissance. Thames & Hudson. OCLC 636355191.

- Jones, Philip James (1997). The Italian city-state from commune to signoria. Oxford & New York: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9786610806577. OCLC 252653924.

- Keller, Hagen (1979). Adelsherrschaft und städtische Gesellschaft in Oberitalien, 9. bis 12. Jahrhundert [Nobility and urban society in northern Italy, 9th to 12th centuries] (in German). Vol. 52. Tübingen: M. Niemeyer Verlag. ISBN 9783484800885. OCLC 612442612.

- Litta Biumi, Pompeo (1819–1884). Visconti di Milano. Famiglie celebri italiane (in Italian). Milano: Luciano Basadonna Editore. OCLC 777242652. Retrieved 2020-04-15.

- Menant, François (2005). L'Italie des communes (1100–1350) [Italy of the communes] (in French). Édition Belin. ISBN 9782701140445.

- Muir, Dorothy Erskine (1924). A history of Milan under the Visconti. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd.

- Romano, Serena (2014). "Milan (and Lombardy): Art and Architecture, 1277–1535". In Gamberini, Andrea (ed.). A companion to late medieval and early modern Milan. The distinctive features of an Italian state. Leiden & Boston: Brill. pp. 214–247. ISBN 9789004284128. OCLC 897378766.

- Rossiter, William T. (2010). Chaucer and Petrarch. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer. ISBN 9781846157967. OCLC 738478094.

- Rückert, Peter (2008). "Fürstlicher Transfer um 1400: Antonia Visconti und ihre Schwestern". In Rückert, Peter; Sönke, Lorenz (eds.). Die Visconti und der deutsche Südwesten. Kulturtransfer im Spätmittelalter (in German). Ostfildern: Jan Thorbeck Verlag. pp. 11–32. ISBN 9783799555111. OCLC 298988901.

- Visconti, Alessandro (1967). Storia di Milano. A cura della Famiglia Meneghina e sotto gli auspici del Comune di Milano [History of Milan. Edited by Famiglia Meneghina and under the auspices of the Commune of Milan] (in Italian). Milano: Ceschina. OCLC 2872335.

- Vincenti, Antonello (1981). I Castelli viscontei e sforzeschi (in Italian). Milano: Rusconi Libri S.p.A. Immagini. OCLC 8446824.

- Welch, Evelyn (1989). "Galeazzo Maria Sforza and the Castello di Pavia, 1469". The Art Bulletin. 71: 351–375. doi:10.1080/00043079.1989.10788512.

- Welch, Evelyn S. (1995). Art and Authority in Renaissance Milan. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300063516. OCLC 32429850.

- Wilkins, Ernest Hatch (1958). Petrarch's eight years in Milan. Cambridge, MA: Mediaeval Academy of America. hdl:2027/heb.31117. OCLC 926390871.