Garrett Park, Maryland

Garrett Park, Maryland | |

|---|---|

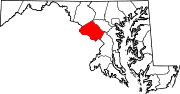

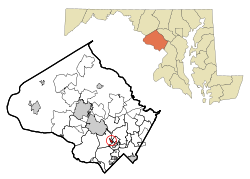

Location in Montgomery County and in Maryland | |

| Coordinates: 39°02′10″N 77°05′37″W / 39.03611°N 77.09361°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Montgomery |

| Incorporated | 1898[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 0.25 sq mi (0.65 km2) |

| • Land | 0.25 sq mi (0.65 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 318 ft (97 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 996 |

| • Density | 3,968.13/sq mi (1,531.62/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 20896 |

| Area code(s) | 301, 240 |

| FIPS code | 24-31525 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2390199[3] |

| Website | www |

Garrett Park is a town in Montgomery County, Maryland, United States. It was named after a former president of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, Robert W. Garrett. The population was 996 at the 2020 census.[4] Garrett Park is home to Garrett Park Elementary School, located just outside the town proper.

History

[edit]

Garrett Park was an early planned community, originally promoted by businessman Henry W. Copp, who purchased the land in 1886. Copp wanted to build a suburban development reminiscent of an English village, and even went so far as to name the streets after locations in the novels of the English author Walter Scott, such as Kenilworth and Strathmore. Copp worked in conjunction with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, which in 1893 built a train station.[5] Builders were given reduced rates to transport workers and materials to the town site, and new residents were given free trips to move in. The town lies along the former B&O railway corridor (now used by CSX, Amtrak, and MARC). It was named for John Work Garrett, who had led the B&O for nearly three decades, including during the American Civil War. Copp limited commercial development in the community. Today the town has a four-star restaurant, post office, and farmer's market.

Garrett Park incorporated as a town in 1898, at which time it had thirty buildings and approximately 100 residents.[6] However, rail suburbs did not catch on, and the community stagnated as automobiles replaced commuter trains and streetcars. In the 1920s, another company built approximately 50 more houses, now including garages.[7] Sections of the town are included in the Garrett Park Historic District, listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1975.[8] For example, Garrett Park's first school house, designed in 1928 by prominent local architect Howard Wright Cutler and now preserved as part of a residential home, is a designated historic site by the Maryland Historical Trust.[9] In 1977, the town became a declared arboretum, maintaining a tree inventory of all town trees and a scheduled tree planting schedule. In May 1982 the townspeople of Garrett Park voted 245 to 46 to ban the production, transportation, storage, processing, disposal, or use of nuclear weapons within the town. This made Garrett Park the first nuclear-weapon-free zone in the United States.[10]

Geography

[edit]

Garrett Park is located in southern Montgomery County at 39°2' North, 77°6' West. It is just west of Kensington, due north of Bethesda, northwest of Silver Spring, and southeast of Rockville. It is approximately halfway between Rockville and Silver Spring. Rock Creek Stream Valley Park, operated by Montgomery County, is located along the town's southeast borders.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 0.25 square miles (0.65 km2), all of it land.[2]

Garrett Park is primarily a residential town, with a post office, and a few small businesses. The only road open to automotive traffic into or out of Garrett Park is Maryland State Highway 547 (Strathmore Avenue). The town is served by the MARC Train Brunswick Line. The town is unusual in that residents pick up their mail at the post office in person, rather than having home delivery.[11]

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 175 | — | |

| 1910 | 185 | 5.7% | |

| 1920 | 159 | −14.1% | |

| 1930 | 295 | 85.5% | |

| 1940 | 406 | 37.6% | |

| 1950 | 524 | 29.1% | |

| 1960 | 965 | 84.2% | |

| 1970 | 1,276 | 32.2% | |

| 1980 | 1,178 | −7.7% | |

| 1990 | 884 | −25.0% | |

| 2000 | 917 | 3.7% | |

| 2010 | 992 | 8.2% | |

| 2020 | 996 | 0.4% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[12] | |||

2010 census

[edit]As of the census[13] of 2010, there were 992 people, 380 households, and 277 families residing in the town. The population density was 3,815.4 inhabitants per square mile (1,473.1/km2). There were 401 housing units at an average density of 1,542.3 per square mile (595.5/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 91.6% White, 1.3% African American, 0.2% Native American, 3.6% Asian, 0.4% from other races, and 2.8% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 5.5% of the population.

There were 380 households, of which 35.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 61.3% were married couples living together, 8.9% had a female householder with no husband present, 2.6% had a male householder with no wife present, and 27.1% were non-families. 20.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.61 and the average family size was 3.05.

The median age in the town was 46.8 years. 25.5% of residents were under the age of 18; 5.1% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 16.5% were from 25 to 44; 34.8% were from 45 to 64; and 18.2% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the town was 48.0% male and 52.0% female.

2000 census

[edit]As of the census[14] of 2000, there were 917 people, 347 households, and 266 families residing in the town. The population density was 3,427.8 inhabitants per square mile (1,323.5/km2). There were 356 housing units at an average density of 1,330.8 per square mile (513.8/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 91.82% White, 0.87% Black or African American, 0.22% Native American, 3.05% Asian, 1.53% from other races, and 2.51% from two or more races. 2.51% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 347 households, out of which 35.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 68.0% were married couples living together, 6.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 23.3% were non-families. 18.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.64 and the average family size was 3.02.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 25.4% under the age of 18, 3.1% from 18 to 24, 21.6% from 25 to 44, 31.7% from 45 to 64, and 18.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 45 years. For every 100 females, there were 91.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 85.9 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $106,883, and the median income for a family was $126,662. Males had a median income of $96,588 versus $66,563 for females. The per capita income for the town was $50,305. None of the families and 0.8% of the population were living below the poverty line, including no under 18 and 2.6% of those over 64.

Law and government

[edit]The Garrett Park Chapel was purchased by the town in 1968, and now serves as the town hall. Its form of government follows a strong-mayor structure as defined by the following characteristics specified in the town charter: the mayor and council members are elected separately by the residents and hold separate and distinct powers and functions of town governance. The mayor serves as chief executive officer and oversees the administrative operations of the town government, responsible for executing the town's budget and operations. The mayor appoints with approval by the council a clerk-treasurer, whose role as chief financial officer is responsible for formulating the town's fiscal year budget under supervision of the mayor for council review and adoption.

The council is the legislative body, comprising five elected officials. Each council member is elected for a two–year term, with two members elected in even-numbered years, three in odd-numbered years. As the legislative body, the council sets policy by ordinance or resolution and adopts the annual budget by approving the allocation of appropriated funds by ordinance. All executive powers of the town are vested in the mayor, who is elected separately by the town residents (in the even-numbered years) and also serves a two-year term.

Mayor or city executive

[edit]Recent mayors/chief executive officers (dual roles) of the town of Garrett Park (elected for two-year terms):

- Nancy M. Floreen (elected to the County Council of Montgomery County in the 2002 election)

- Peter Benjamin (2003–2004)

- Carolyn Shawaker (2005-2007)

- Chris Keller (2007-2012)

- Peter Benjamin (2012-2018)

- Kathryn (Kacky) Chantry (2018-2022)

- Joanna Roufa Welch (2022–2024)

- Christopher Keller (2024-)

Education

[edit]Garrett Park is served by the Montgomery County Public Schools.

Schools that serve the town include:

- Garrett Park Elementary School, in North Bethesda, adjacent to Garrett Park[15][16][17]

- Tilden Middle School

- Walter Johnson High School

The Washington Japanese Language School (WJLS, ワシントン日本語学校 Washington Nihongo Gakkō), a supplementary weekend Japanese school, has its school office at Quinn Hall of the Holy Cross Church in North Bethesda, adjacent to Garrett Park.[16][17][18] The WJLS holds its classes in Bethesda.[18][19] The institution, giving supplemental education to Japanese-speaking children in the Washington DC area, was founded in 1958,[20] making it the oldest Japanese government-sponsored supplementary school in the U.S.[21]

Transportation

[edit]The only state highway serving Garrett Park is Maryland Route 547. MD 547 connects the town with Maryland Route 355 to the west and Maryland Route 185 to the east, which both provide connections to Interstate 495 (the Capital Beltway) and to Washington, D.C.

References

[edit]- ^ "Garrett Park". Maryland Manual. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

- ^ a b "2022 U.S. Gazetteer Files: Maryland". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 1, 2023.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Garrett Park, Maryland

- ^ a b "P1. Race – Garrett Park town, Maryland: 2020 DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171)". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved June 1, 2023.

- ^ Garrett Park in 1898 Archived May 23, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Town of Garrett Park

- ^ "History of the Town | Garrett Park, MD". www.garrettparkmd.gov. Archived from the original on October 31, 2018. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- ^ Offutt, William; Sween, Jane (1999). Montgomery County: Centuries of Change. American Historical Press. pp. 166–167.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- ^ Inventory of Historical Places, Maryland Historical Trust

- ^ Schmidt, David (June 29, 1991). Citizen Lawmakers. Temple University Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-87722-903-2.

- ^ "Garrett Park, MD". www.garrettparkmd.gov. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Home. Garrett Park Elementary School. Retrieved on April 30, 2014. "4810 Oxford Street, Kensington, MD 20895"

- ^ a b "Map" (Archive). Town of Garrett Park. Retrieved on April 30, 2014.

- ^ a b "2010 CENSUS - CENSUS BLOCK MAP: North Bethesda CDP, MD" (Archive). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on April 30, 2014.

- ^ a b "Home" (Archive). Washington Japanese Language School. Retrieved on August 11, 2020. "学校事務局 Holy Cross Church, Quinn Hall 2F. 4900 Strathmore Avenue, Garrett Park, MD 20896[...]校舎 ストーンリッジ校 Stone Ridge School of the Sacred Heart 9101 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20814"

- ^ "SRMap2015.pdf[permanent dead link]." Washington Japanese Language School. Retrieved on April 16, 2015.

- ^ Washington Japanese Language School. "About Washington Japanese Language School (WJLS) | ワシントン日本語学校". Archived from the original on August 11, 2020. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- ^ "Andrew M. Saidel" (Archive). Japan-America Society of Greater Philadelphia (JASGP; フィラデルフィア日米協会とは). Retrieved on April 16, 2015.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Garrett Park Archived February 14, 2004, at the Wayback Machine at the Maryland State Archives

- "Seeing a Future Along Old Tracks" Sowers, Scott, Washington Post, July 8, 2006, Page F01