Love's Labour's Won

Love's Labour's Won is a lost play attributed by contemporaries to William Shakespeare, written before 1598 and published by 1603, though no copies are known to have survived. Scholars dispute whether it is a true lost work, possibly a sequel to Love's Labour's Lost, or an alternative title to a known Shakespeare play.

Evidence

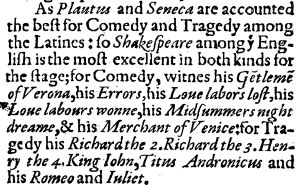

[edit]The first mention of the play occurs in Francis Meres' Palladis Tamia, Wits Treasury (1598) in which he lists a dozen Shakespeare plays. His list of Shakespearean comedies reads:

for Comedy, witnes his Gẽtlemẽ of Verona, his Errors, his Loue labors lost, his Loue labours wonne, his Midsummers night dreame, & his Merchant of Venice

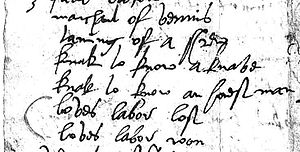

The August 1603 book list of the stationer Christopher Hunt lists the play as printed in quarto among other works by Shakespeare:

marchant of vennis, taming of a shrew, ...loves labor lost, loves labor won.

Theories

[edit]Shakespeare scholars have several theories about the play.

Sequel to Love's Labour's Lost

[edit]One theory is that Love's Labour's Won may be a lost sequel to Love's Labour's Lost, depicting the further adventures of the King of Navarre, Berowne, Longaville, and Dumain, whose marriages were delayed at the end of Love's Labour's Lost.[1] In the final moments of Love's Labour's Lost the weddings that customarily close Shakespeare's comedies are unexpectedly deferred for a year without any obvious plot purpose, which would allow for a sequel.[2][3] Critic Cedric Watts imagined what a sequel might look like:

After the year of waiting, the King and lords would meet again and compare experiences; each would, in various ways, have failed to be as diligently faithful and austere as he had been enjoined by his lady to be.[2]

Against this it must be observed that Elizabethan playwrights almost never wrote sequels to comedies. Sequels were written for historical plays or, less commonly, for tragedies.[4]

Alternative name for existing play

[edit]

Another theory is that Love's Labour's Won was an alternative name for a known play. This would explain why it was not printed under that name in the First Folio of Shakespeare's complete dramatic works in 1623, for which the sequel theory has no obvious explanation.

A longtime theory held that Love's Labour's Won was an alternative name for The Taming of the Shrew, which had been written several years earlier and is noticeably missing from Meres' list. But in 1953, Solomon Pottesman, a London-based antiquarian book dealer and collector, discovered the August 1603 book list of the stationer Christopher Hunt, which lists as printed in quarto:

marchant of vennis, taming of a shrew, knak to know a knave [unknown author], knak to know an honest man [unknown author], loves labor lost, loves labor won.

The find provided evidence that the play might be a distinct work that had been published but lost and not an early title of The Taming of the Shrew. However, this evidence is not decisive. Another playwright had written a play called The Taming of a Shrew which was published in quarto in 1594, whereas Shakespeare's Shrew play was not published until the 1623 Folio. Therefore, it is possible that Shakespeare originally titled his Shrew play Love's Labour's Won in order to distinguish it from the rival play.[4]

Yet another possibility is that the name is an alternative title for another Shakespearean comedy not listed by Meres or Hunt.[5] Much Ado About Nothing, commonly believed to be written around 1598,[6] is often suggested. For example, Henry Woudhuysen's Arden edition (third series) of Love's Labour's Lost lists a number of striking similarities between the two plays. Much Ado about Nothing is also listed under another alternative title – Benedick and Beatrice – in several book sellers' catalogues.

Leslie Hotson speculated that Love's Labour's Won was the former title of Troilus and Cressida, which did not appear in Palladis Tamia. This view that has been criticised by Kenneth Palmer for requiring a "forced interpretation of the play". In addition, Troilus and Cressida is generally considered to have been written around 1602.[7]

David Grote argues that it was another name for As You Like It. He suggests that titles for comedies were often generic – several plays could be called "As You Like It" or "All's Well that Ends Well", for example, and that names were not fixed until repeated publication. He suggests that As You Like It began as a sequel to Love's Labour's Lost, but was later revised when Robert Armin replaced William Kempe as the principal comic actor in Shakespeare's theatre company, the Lord Chamberlain's Men.[8]

Use of the title

[edit]In their 2014 season commemorating the centenary of the commencement of World War I hostilities, the Royal Shakespeare Company co-opted the title in performing Much Ado about Nothing under the name Love's Labour's Won (also known as Much Ado about Nothing). It was staged as a companion piece to Love's Labour's Lost. The pair of plays bookended the period of the war. Love's Labour's Lost was set at the beginning of the war in 1914, with Love Labour's Won set at its end in 1918, with the male characters returning home after the final victory.[9]

In other popular culture

[edit]The play was featured as a plot device in the 1948 novel Love Lies Bleeding (1948) by Edmund Crispin, in which the discovery of a copy of the play triggers a series of murders.

The writing of the play is a major plot point in the 2007 Doctor Who episode "The Shakespeare Code" where The Tenth Doctor witnesses the writing of the play firsthand.

It was also used in the book series The 39 Clues as a minor plot device in the final book of the first series.

In Harry Turtledove's alternate history novel Ruled Britannia, depicting a Spanish-ruled England in which Shakespeare is involved in the clandestine resistance, depicts him writing a play called Love's Labour's Won. However, this play seems to be simply "our" Love's Labour's Lost, as Shakespeare is shown making a last-minute change of Don Armado's nationality from Spanish to Italian, to avoid insulting the overlords.

References

[edit]- ^ Berryman, John (2001), Shakespeare: essays, letters and other writings, Tauris Parke Paperbacks, p. lii

- ^ a b Watts, Cedric, "Shakespeare's feminist play?" in Sutherland, John & Watts, Cedric, Henry V, War Criminal? And Other Shakespeare Puzzles, Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2000, p. 178.

- ^ Paul A. Olson, Beyond a Common Joy: An Introduction to Shakespearean Comedy, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, NE, 2008, p. 56.

- ^ a b Baldwin, T. W. Shakespere’s Love’s Labor’s Won. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1957.

- ^ "Love's Labours Won". Shakesper. 2005. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- ^ Textual notes to Much Ado about Nothing in The Norton Shakespeare (W. W. Norton & Co., 1997 ISBN 0-393-97087-6), p. 1387

- ^ Palmer, Kenneth (1982). "Introduction". Troilus and Cressida. Second (Arden Shakespeare ed.). London: Methuen. p. 18. ISBN 0-416-17790-5.

- ^ David Grote, The Best Actors in the World: Shakespeare and His Acting Company, Greenwood Press, Westport, CT, 2002, p. 60.

- ^ "Love's Labours Won". What's On. RSC. October 2014 – March 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

Bibliography

[edit]- Baldwin, T.W. Shakespeare's Love's Labour's Won: New Evidence from the Account Books of an Elizabethan Bookseller. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1957.