Tourism in Italy

Tourism in Italy is one of the largest economic sectors of the country. With 60 million tourists per year (2023), Italy is the fourth most visited country in international tourism arrivals. According to 2018 estimates by the Bank of Italy, the tourism sector directly generates more than five per cent of the national GDP (13 per cent when also considering the indirectly generated GDP) and represents over six per cent of the employed.[7][8]

People have visited Italy for centuries, yet the first to visit the peninsula for tourist reasons were aristocrats during the Grand Tour, beginning in the 17th century, and flourishing in the 18th and 19th centuries.[9] This was a period in which European aristocrats, many of whom were British and French, visited parts of Europe, with Italy as a key destination.[9] For Italy, this was in order to study ancient architecture, local culture and to admire the natural beauties.[10]

Nowadays the factors of tourist interest in Italy are mainly culture, cuisine, history, fashion, architecture, art, religious sites and routes, naturalistic beauties, nightlife, underwater sites and spas. Winter and summer tourism are present in many locations in the Alps and the Apennines,[11] while seaside tourism is widespread in coastal locations along the Mediterranean Sea.[12] Small, historical and artistic Italian villages are promoted through the association I Borghi più belli d'Italia (literally "The Most Beautiful Villages of Italy"). Italy is among the countries most visited in the world by tourists during the Christmas holidays.[13] Rome is the 3rd most visited city in Europe and the 12th in the world, with 9.4 million arrivals in 2017[14] while Milan is the 5th most visited city in Europe and the 16th in the world,[15][16] with 8.81 million tourists.[17] In addition, Venice and Florence are also among the world's top 100 destinations. Italy is also the country with the highest number of UNESCO World Heritage Sites in the world (60).[18] Out of Italy's 60 heritage sites, 54 are cultural and 6 are natural.[19]

The Roman Empire, Middle Ages, Renaissance and the following centuries of the history of Italy have left many cultural artefacts that attract tourists.[20] In general, the Italian cultural heritage is the largest in the world since it consists of 60 to 75 percent of all the artistic assets that exist on each continent,[21] with over 4,000 museums, 6,000 archaeological sites, 85,000 historic churches and 40,000 historic palaces, all subject to protection by the Italian Ministry of Culture.[22] As of 2018, the Italian places of culture (which include museums, attractions, parks, archives and libraries) amounted to 6,610. Italy is the leading cruise tourism destination in the Mediterranean Sea.[23]

In Italy, there is a broad variety of hotels, going from 1-5 stars. According to ISTAT, in 2017, there were 32,988 hotels with 1,133,452 rooms and 2,239,446 beds.[24] As for non-hotel facilities (campsites, tourist villages, accommodations for rent, agritourism, etc.), in 2017 their number was 171,915 with 2,798,352 beds.[24] The tourist flow to coastal resorts is 53 percent; the best equipped cities are Grosseto for farmhouses (217), Vieste for campsites and tourist villages (84) and Cortina d'Ampezzo mountain huts (20).[25][26]

History

[edit]

Beginnings

[edit]People have visited Italy for centuries, yet the first to visit the peninsula for touristic reasons were aristocrats during the Grand Tour, beginning in the 17th century, and flourishing in the 18th and the 19th century.[9]

Rome, as the capital of the Roman Empire, attracted thousands to the city and country from all over the empire, which included a great part of Europe, Western Asia and Northern Africa. Traders and merchants came to Italy from several different parts of the world. When the empire fell in 476 AD, Rome was no longer the epicentre of European politics and culture; on the other hand, it was the base of the papacy, which then governed the growing Christian religion, meaning that Rome remained one of Europe's major places of pilgrimage. Pilgrims, for centuries and still today, would come to the city, and that would have been the early equivalent of "tourism" or "religious tourism".[27] The trade empires of Venice, Pisa and Genoa meant that several traders, businessmen and merchants from all over the world would also regularly come to Italy. In the 16th and early 17th centuries, with the height of the Renaissance, several students came to Italy to study Italian architecture.[28]

Grand Tour

[edit]Real "tourism" only affected Italy in the second half of the 17th century, with the beginning of the Grand Tour. This was a period in which European aristocrats, many of whom were British, visited parts of Europe, with Italy as a key destination.[9] For Italy, this was in order to study ancient architecture, local culture and to admire the natural beauties.[10] The Grand Tour was in essence triggered by the book Voyage to Italy, by Roman Catholic priest Richard Lassels, and published in 1670.[29][30] Due to the Grand Tour, tourism became even more prevalent – making Italy one of the most desired destinations for millions of people.[31] Once inside what would be modern-day Italy, these tourists would begin by visiting Turin for a short while. On the way there, Milan was also a popular stop, yet a trip to the city was not considered essential, and several passed by or simply stayed for a short period of time. If a person came via boat, then they would remain for a few days in Genoa. Yet, the main destination in Northern Italy was Venice, which was considered a vital stop,[29] as well as cities around it such as Verona, Vicenza and Padua.

As the Tour went on, Tuscan cities were also very important itinerary stops. Florence was a major attraction, and other Tuscan towns, such as Siena, Pisa, Lucca and San Gimignano, were also considered important destinations. The most prominent stop in Central Italy, however, was Rome, a major centre for the arts and culture, as well as an essential city for a Grand Tourist.[29] Later, they would go down to the Bay of Naples,[29] and after their discovery in 1710, Pompeii and Herculaneum were popular too. Sicily was considered a significant part of the trail, and several, such as Goethe, visited the island.

Mass tourism

[edit]Throughout the 17th to 18th centuries, the Grand Tour was mainly reserved for academics or the elite. Nevertheless, circa 1840,[29] rail transport was introduced and the Grand Tour started to fall slightly out of vogue; hence, the first form of mass tourism was introduced. The 1840s saw the period in which the Victorian middle classes toured the country. Several Americans were also able to visit Italy, and many more tourists came to the peninsula. Places such as Venice, Florence, Rome, Naples and Sicily still remained the top attractions.

Like many other Europeans, Italians rely heavily on public transport. Italy is a relatively small country and distances are reduced.[32]

As the century progressed, fewer cultural visits were made, and there was an increase in tourists coming for Italy's nature and weather. The first seaside resorts, such as those on the Ligurian coast, around Venice, coastal Tuscany and Amalfi, became popular. This vogue of summer holidays heightened in the fin-de-siècle epoch, when numerous "Grand Hotels" were built (including places such as Sanremo, Lido di Venezia, Viareggio and Forte dei Marmi). Islands such as Capri, Ischia, Procida and Elba grew in popularity, and the Northern lakes, such as Lake Como, Maggiore and Garda were more frequently visited. Tourism to Italy remained very popular until the late-1920s and early-1930s, when, with the Great Depression and economic crisis, several could no longer afford to visit the country; the increasing political instability meant that fewer tourists came. Only old touristic groups, such as the Scorpioni, remained alive.

After a big slump in tourism beginning from approximately 1929 and lasting after World War II, Italy returned to its status as a popular resort, with the Italian economic miracle and raised living standards; films such as La Dolce Vita were successful abroad, and their depiction of the country's perceived idyllic life helped raise Italy's international profile. By this point, with higher incomes, Italians could also afford to go on holiday; coastline resorts saw a soar in visitors, especially in Romagna. Many cheap hotels and pensioni (hostels) were built in the 1960s, and with the rise of wealth, by now, even a working-class Italian family could afford a holiday somewhere along the coast. The late 1960s also brought mass popularity to mountain holidays and skiing; in Piedmont and the Aosta Valley, numerous ski resorts and chalets started being built. The 1970s also brought a wave of foreign tourists to Italy in search of a sentimental trip,[33] since Mediterranean destinations saw a rise in global visitors.

Despite this, by the late 1970s and early 1980s, economic crises and political instability meant that there was a significant slump in the Italian tourist industry, as destinations in the Far East or South America rose in popularity.[34] Yet, by the late-1980s and early-1990s, tourism saw a return to popularity, with cities such as Milan becoming more popular destinations. Milan saw a rise in tourists since it was ripening its position as a worldwide fashion capital.

Land and climate

[edit]Geography

[edit]

Italy is located in southern Europe and it is also considered a part of western Europe,[35] between latitudes 35° and 47° N, and longitudes 6° and 19° E. To the north, Italy borders Switzerland, France, Austria and Slovenia and is roughly delimited by the Alpine watershed, enclosing the Po Valley and the Venetian Plain. To the south, it consists of the entirety of the Italian Peninsula crossed by the Apennines and the two Mediterranean islands of Sicily and Sardinia, in addition to many smaller islands. The sovereign states of San Marino and the Vatican City are enclaves within Italy,[36][37] while Campione d'Italia is an Italian exclave in Switzerland.[38]

Italy is part of the Northern Hemisphere. The country's total area is 301,230 square kilometres (116,306 sq mi), of which 294,020 km2 (113,522 sq mi) is land and 7,210 km2 (2,784 sq mi) is water.[39] Including islands, Italy has a coastline of 7,900 km (4,900 mi) on the Adriatic Sea, Ionian Sea, Tyrrhenian Sea, Ligurian Sea, Sea of Sardinia and Strait of Sicily, and borders shared with France (488 km (303 mi)), Austria (430 km (267 mi)), Slovenia (232 km (144 mi)) and Switzerland (740 km (460 mi)). San Marino (39 km (24 mi)) and Vatican City (3.2 km (2.0 mi)), both enclaves, account for the remainder.[39]

Climate

[edit]

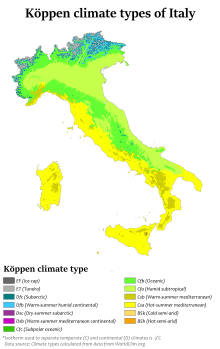

The climate of Italy is influenced by the large body of water of the Mediterranean Sea that surrounds Italy on every side except the north. These seas constitute a reservoir of heat and humidity for Italy. Within the southern temperate zone, they determine a particular climate called Mediterranean climate with local differences due to the geomorphology of the territory, which tends to make its mitigating effects felt, especially in high pressure conditions.

Because of the length of the peninsula and the mostly mountainous hinterland, the climate of Italy is highly diverse. The inland northern areas of Italy (for example Turin, Milan, and Bologna) have a relatively cool, mid-latitude version of the Humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa), while the coastal areas of Liguria and the peninsula south of Florence generally fit the Mediterranean climate profile (Köppen climate classification Csa).[40]

Conditions on the coast are different from those in the interior, particularly during winter months when the higher altitudes tend to be cold, wet, and often snowy. The coastal regions have mild winters and warm and generally dry summers, although lowland valleys can be quite hot in summer. Between the north and south there can be a considerable difference in temperature, above all during the winter: on some winter days it can be −2 °C (28 °F) and snowing in Milan, while it is 8 °C (46.4 °F) in Rome and 20 °C (68 °F) in Palermo. Temperature differences are less extreme in the summer.

Transport

[edit]

Transport infrastructure in Italy is well developed. Italy's paved road network is widespread, with a total length of about 487,700 km (303,000 mi).[42] It comprises both an extensive motorway network (7,016 km (4,360 mi)), called autostrade, mostly toll roads, and national and local roads. The Strade Statali is the Italian national network of state highways. The total length for this network is about 25,000 km (16,000 mi).[43] Strade Regionali ("regional roads") are a type of Italian road maintained by the regions they traverse. A regional road is less important than a state highway, but more important than a Strada Provinciale ("provincial road"). A provincial road is more important than a Strada Comunale ("municipal road").

The national railway network is also extensive, especially in the north, totalizing 16,862 km of which 69% are electrified and on which 4,937 locomotives and railcars circulate. It is the 12th largest in the world, and is operated by state-owned Ferrovie dello Stato, while the rail tracks and infrastructure are managed by Rete Ferroviaria Italiana. While a number of private railroads exist and provide mostly commuter-type services, the national railway also provides sophisticated high-speed rail service that joins the major cities.

Italy is the fifth in Europe by number of passengers by air transport, with about 148 million passengers or about 10% of the European total in 2011.[44] There are approximately 130 airports in Italy, of which 99 have paved runways (including the two hubs of Leonardo Da Vinci International in Rome and Malpensa International in Milan).

In 2004 there were 43 major seaports including the Port of Genoa, the country's largest and the third busiest by cargo tonnage in the Mediterranean Sea. Due to the increasing importance of the maritime Silk Road with its connections to Asia and East Africa, the Italian ports for Central and Eastern Europe have become important in recent years. In particular, the deep water port of Trieste in the northernmost part of the Mediterranean Sea is the target of Italian, Asian and European investments.[45][46] The national inland waterway network comprises 1,477 km (918 mi) of navigable rivers and channels. In the northern regions of Lombardy and Veneto, commuter ferry boats operate on Lake Garda and Lake Como to connect towns and villages at both sides of the lakes.

Seven Italian cities have metro systems:

| City | Name | Lines | Length | Stations | Opening |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brescia | Brescia Metro | 1 | 13.7 km (8.5 mi) | 17 | 2013 |

| Catania | Catania Metro | 1 | 8.8 km (5.5 mi) | 10 | 1999 |

| Genoa | Genoa Metro | 1 | 7.1 km (4.4 mi) | 8 | 1990 |

| Milan | Milan Metro | 5 | 102.5 km (63.7 mi) | 119 | 1964 |

| Naples | Naples Metro | 2 | 20.3 km (12.6 mi) | 23 | 1993 |

| Rome | Rome Metro | 3 | 60 km (37 mi) | 75 | 1955 |

| Turin | Turin Metro | 1 | 15.1 km (9.4 mi) | 23 | 2006 |

Tourist flows

[edit]

The peaks of tourist flows in Italy are recorded in winter, due to the Christmas and New Year's Day holidays,[47] in spring, due to the Easter holidays,[48] and in summer, due to the favourable climate.[49]

For internal tourism, peaks of tourist flows are also recorded on the occasion of the three national civil holidays, the Festa della liberazione (25 April), the Festa dei lavoratori (1 May) and the Festa della Repubblica (2 June),[50][51] as well as for three religious holidays, the Ferragosto (15 August),[52] the Ognissanti (1 November)[53] and the Festa dell'Immacolata Concezione (8 December).[54]

Statistics

[edit]Arrivals by country

[edit]Most visitors arriving in Italy in 2022 were citizens of the following countriesl:[55]

| # | Country | Arrivals |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12.736.289 | |

| 2 | 5.399.785 | |

| 3 | 4.599.412 | |

| 4 | 3.256.823 | |

| 5 | 3.123.880 | |

| 6 | 2.765.066 | |

| 7 | 2.318.706 | |

| 8 | 1.867.568 | |

| 9 | 1.508.103 | |

| 10 | 1.286.928 | |

| 11 | 1.157.635 | |

| 12 | 869.054 | |

| 13 | 864.653 | |

| 14 | 786.994 | |

| 15 | 710.691 | |

| 16 | 688.771 | |

| 17 | 685.880 | |

| 18 | 681.269 | |

| 19 | 666.128 | |

| 20 | 607.114 | |

| 21 | 537.772 | |

| 22 | 533.092 | |

| 23 | 530.392 | |

| 24 | 458.073 | |

| 25 | 416.635 | |

| 26 | 393.258 | |

| 27 | 386.259 | |

| 28 | 375.155 | |

| 29 | 348.815 | |

| 30 | 330.010 | |

| Total arrivals | 55.086.852 |

Nights spent by country

[edit]| Rank | Country | Nights spent |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 58.699.396 | |

| 2 | 16.302.928 | |

| 3 | 13.842.473 | |

| 4 | 13.674.263 | |

| 5 | 10.806.529 | |

| 6 | 10.320.382 | |

| 7 | 9.520.238 | |

| 8 | 6.203.982 | |

| 9 | 5.819.444 | |

| 10 | 5.789.755 | |

| 11 | 5.355.907 | |

| 12 | 4.751.383 | |

| 13 | 4.127.567 | |

| 14 | 3.058.530 | |

| 15 | 2.881.036 | |

| 16 | 2.824.686 | |

| 17 | 2.765.252 | |

| 18 | 2.665.209 | |

| 19 | 2.544.362 | |

| 20 | 2.372.891 | |

| 21 | 2.210.468 | |

| 22 | 1.815.223 | |

| 23 | 1.247.398 | |

| 24 | 903.868 | |

| 17.437.507 | ||

| 5.311.276 | ||

| Total | 220.662.684 |

Italy overall had 420.63 million visitor nights in 2017, of which 210.66 million were of foreign guests (50.08 per cent). With 37.04 million nights spent in hotels, hostels or clinics, the Metropolitan City of Venice has the most visitors.[56]

Italian regions by number of visitors

[edit]According to regional data, in 2018 tourism presences in Italy amounted to 436 million (216 million residents and 220 million non-residents).[57]

With 71 million nights spent in tourist accommodation establishments, Veneto has the highest number of visitors and ranks sixth in Europe.[58][59]

Below is a table with the most visited regions in Italy (data as of 2019)

| # | Region | Total nights | Resident | Non resident |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 71.236.630 | 23.068.000 | 48.168.630 | |

| 2 | 52.074.506 | 20.941.947 | 31.132.559 | |

| 3 | 48.077.301 | 22.317.283 | 25.760.018 | |

| 4 | 40.647.799 | 29.748.437 | 10.611.605 | |

| 5 | 40.482.939 | 16.229.378 | 24.253.561 | |

| 6 | 39.029.255 | 14.637.466 | 24.391.789 | |

| 7 | 22.013.245 | 11.383.367 | 10.629.878 | |

| 8 | 15.441.469 | 11.598.644 | 3.842.825 | |

| 9 | 15.145.885 | 7.418.767 | 7.727.118 | |

| 10 | 15.114.931 | 7.483.403 | 7.631.528 | |

| 11 | 15.074.888 | 8.932.884 | 6.142.004 | |

| 12 | 14.889.951 | 8.351.424 | 6.538.527 | |

| 13 | 10.370.800 | 8.647.855 | 2.417.288 | |

| 14 | 9.509.423 | 7.315.264 | 2.194.159 | |

| 15 | 9.052.850 | 3.898.039 | 5.154.811 | |

| 16 | 6.176.702 | 5.383.234 | 793.468 | |

| 17 | 5.889.224 | 3.810.497 | 2.078.727 | |

| 18 | 3.625.616 | 2.113.001 | 1.512.615 | |

| 19 | 2.733.969 | 2.392.796 | 296.230 | |

| 20 | 448.600 | 127.283 | 341.173 | |

| 436.739.271 | 216.076.587 | 220.662.684 |

Italian provinces/metropolitan cities by number of visitors

[edit]Below is a table with the most visited province/metropolitan cities in Italy (data as of 2017)

| Rank | Province/Metropolitan City | # of nights in 2017[56] |

of whom foreign visitors[56] |

Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Venice | 37,042,454 | 27,477,075 | |

| 2 | Bolzano/Bozen | 32,400,662 | 22,125,350 | |

| 3 | Rome | 29,833,225 | 7,046,098 | |

| 4 | Trento | 17,776,030 | 7,412,103 | |

| 5 | Verona | 17,293,792 | 13,388,082 | |

| 6 | Rimini | 15,967,490 | 3,808,354 | |

| 7 | Milan | 15,468,199 | 9,291,198 | |

| 8 | Florence | 14,716,466 | 10,780,968 | |

| 9 | Naples | 13,161,395 | 7,247,964 | |

| 10 | Brescia | 10,463,688 | 7,472,887 | |

| 11 | Livorno | 8,663,572 | 3,491,172 | |

| 12 | Sassari | 7,492,538 | 4,162,225 | |

| 13 | Turin | 7,046,219 | 1,842,052 | |

| 14 | Ravenna | 6,698,702 | 1,381,666 | |

| 15 | Salerno | 6,029,649 | 2,098,781 | |

| 16 | Savona | 5,717,487 | 1,471,811 | |

| 17 | Grosseto | 5,714,546 | 1,601,673 | |

| 18 | Padua | 5,479,110 | 2,426,489 | |

| 19 | Udine | 5,371,339 | 3,027,318 | |

| 20 | Forlì-Cesena | 5,357,398 | 1,027,558 | |

| 21 | Lecce | 5,048,739 | 949,521 | |

| 22 | Siena | 4,928,092 | 2,880,531 | |

| 23 | Perugia | 4,689,356 | 1,699,019 | |

| 24 | Bologna | 4,607,456 | 2,101,001 | |

| 25 | Foggia | 4,503,604 | 697,073 | |

| 26 | Genoa | 4,082,817 | 1,945,743 | |

| 27 | Belluno | 3,806,806 | 1,208,331 | |

| 28 | Aosta/Aoste | 3,599,402 | 1,434,422 | |

| 29 | Lucca | 3,546,044 | 1,696,020 | |

| 30 | Messina | 3,493,859 | 2,153,932 | |

| 31 | Teramo | 3,419,387 | 523,718 | |

| 32 | Pesaro and Urbino | 3,295,759 | 729,067 | |

| 33 | Cosenza | 3,290,418 | 369,693 | |

| 34 | Imperia | 3,202,619 | 1,324,925 | |

| 35 | Verbania | 3,095,668 | 2,443,754 | |

| 36 | Como | 3,088,807 | 2,375,038 | |

| 37 | Pisa | 3,032,756 | 1,632,412 | |

| 38 | Ferrara | 3,020,136 | 1,142,220 | |

| 39 | Palermo | 2,981,947 | 1,703,615 | |

| 40 | Ancona | 2,954,206 | 536,167 | |

| rest of Italy | 79,247,316 | 42,531,760 | ||

| Total | 420,629,155 | 210,658,786 | ||

Italian cities by number of visitors

[edit]Below is a table with the most visited cities in Italy (data as of 2019)[60]

Italian archaeological sites and museums by number of visitors

[edit]Below is a table with the most visited archaeological sites and museums in Italy (data as of 2019)[61][62]

Italian churches by number of visitors

[edit]Below is a table with the most visited churches in Italy[63]

Factors of tourist interest

[edit]There are many factors that drive tourism interest to Italy.[64]

Artistic-cultural tourism

[edit]

Italy is considered one of the birthplaces of western civilization and a cultural superpower.[67] Divided by politics and geography for centuries until its eventual unification in 1861, Italy's culture has been shaped by a multitude of regional customs and local centres of power and patronage.[68] Italy has had a central role in Western culture for centuries and is still recognised for its cultural traditions and artists. During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, a number of courts competed to attract architects, artists and scholars, thus producing a legacy of monuments, paintings, music and literature. Despite the political and social isolation of these courts, Italy has made a substantial contribution to the cultural and historical heritage of Europe.[69] The country has had a broad cultural influence worldwide, also because numerous Italians emigrated to other places during the Italian diaspora.

The country boasts several world-famous cities. Rome was the ancient capital of the Roman Empire, the seat of the Pope of the Catholic Church, the capital of reunified Italy and the artistic, cultural and cinematographic centre of world relevance. Florence was the heart of the Renaissance, a period of great achievements in the arts at the end of the Middle Ages.[70] Other important cities include Turin, which used to be the capital of Italy and is now one of the world's great centres of automobile engineering. Milan is the industrial and financial capital of Italy and one of the world's fashion capitals. Venice, the former capital of a major financial and maritime power from the Middle Ages to the early modern period, with its intricate canal system attracts tourists from all over the world, especially during the Venetian Carnival and the Biennale. Naples, with the largest historic city centre in Europe and the oldest continuously active public opera house in the world (Teatro di San Carlo). Bologna is the main transport hub of the country, as well as the home of the oldest university in the world and of a worldwide famous cuisine.[71]

Italian art has influenced several major movements throughout the centuries and has produced several great artists, including painters, architects and sculptors. Italy has a vast and important historical heritage,[72] both in terms of the number of artefacts, as well as in terms of conservation, and in terms of intrinsic artistic-cultural value. For example, Italy boasts the largest number of sites indicated in the UNESCO World Heritage List.[73] In general, the Italian cultural heritage is the largest in the world since it consists of 60% to 75% of all the artistic assets that exist on each continent,[21] with over 4,000 museums, 6,000 archaeological sites, 85,000 historic churches and 40,000 historic palaces, all subject to protection by the Italian Ministry of Culture.[22]

In 2013, the value of the artistic and cultural heritage alone was estimated at 5.4% of Italian GDP, approximately €75.5 billion, capable of employing approximately 1.4 million workers.[74] According to the Eurostat report of 2019, Italian tourism is first in Europe in terms of the number of jobs generated (4.2 million) and third for the average visitor expenditure and the share of revenues of the national sector compared to the European total (€48 billion, 12% of the total).[75][76]

There are numerous technology parks in Italy such as the Science and Technology Parks Kilometro Rosso (Bergamo), the AREA Science Park (Trieste), The VEGA-Venice Gateway for Science and Technology (Venezia), the Toscana Life Sciences (Siena), the Technology Park of Lodi Cluster (Lodi), and the Technology Park of Navacchio (Pisa),[77] as well as science museums such as the Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci in Milan, the Natural History Museum in Milan, the Città della Scienza in Naples and the Institute and Museum of the History of Science in Florence.

Seaside tourism

[edit]

Four different seas surround Italy in the Mediterranean Sea from three sides: the Adriatic Sea in the east,[78] the Ionian Sea in the south,[79] and the Ligurian Sea and the Tyrrhenian Sea in the west.[80] Including islands, Italy has a coastline of over 8,000 kilometres (5,000 mi).[81] There are numerous famous coastal stretches.[82]

The Italian Riviera includes nearly all of the coastline of Liguria, extending from the border with France near Ventimiglia eastwards to Capo Corvo, which marks the eastern end of the Gulf of La Spezia.[83][84] Italian coasts also include the Amalfi Coast, Cilentan Coast, Cinque Terre, Coast of the Gods, Costa Verde, Riviera delle Palme, Riviera del Brenta, Costa Smeralda, and Trabocchi Coast, in addition to the bays Venetian Lagoon, Augusta Bay, Bay of Naples and Liscia di Vacca.

Notable beaches includes Baia Domizia in Sessa Aurunca and Cellole, Citara in Forio, Cala Fuili in Cala Gonone, Poetto in Cagliari, Spiaggia del Bacan in Venice, Cala Goloritze in Baunei, Baia delle Zagare in Vieste, Cavoli Beach in Elba, La Sorgente Beach in Portoferraio, Cala dei Gabbiani in Baunei, Cala Cipolla beach in Chia, Cauco Beach in Maiori.[85]

Noteworthy seaside locations includes Taormina, Alghero, Positano, Otranto, Tropea, Porto Santo Stefano, Sirolo, Vieste, Sperlonga, Cesenatico, Sestri Levante, Vasto, Termoli, Maratea, Bibione, Muggia, Amalfi, Atrani, Camogli, Capo Rizzuto, Castiglioncello, Cefalù, Gallipoli, Lerici, Manarola, Monterosso al Mare, Pisciotta, Polignano a Mare, Portofino, Praiano, Ravello, Sciacca, Scilla, Sorrento, Vernazza.[82][86]

Beaches and cliffs are dotted with various accommodation facilities, such as bathing establishments, hotels and restaurants, resorts, agritourism, night and day gathering centres, parks, piers and marinas, as well as numerous historic and artistic centres, which combine an interest in the bathing activities to those for leisure, nature and art.

The Italian seaports are docking points for cruise tourism.[23] Italy is the leading cruise tourism destination in the Mediterranean Sea.[23] Italian seaseaports most frequented by cruise passengers who sail the Mediterranean Sea are Civitavecchia, Genoa, Palermo, Bari, Naples, Savona, Trieste, Monfalcone, Taranto and La Spezia.[87]

Lake tourism

[edit]

There are more than 1000 lakes in Italy,[88] the largest of which is Garda (370 km2 or 143 sq mi). Other well-known subalpine lakes are Lake Maggiore (212.5 km2 or 82 sq mi), whose most northerly section is part of Switzerland, Como (146 km2 or 56 sq mi), one of the deepest lakes in Europe, Orta, Lugano, Iseo, and Idro.[89] Other notable lakes in the Italian peninsula are Trasimeno, Bolsena, Bracciano, Vico, Varano and Lesina in Gargano and Omodeo in Sardinia.[90]

Many Italian lakes are dotted with various accommodation facilities, such as hotels, restaurants and resorts, agritourism, parks, piers and marinas, as well as numerous historic and artistic centres. On the Italian lakes, it is possible to go windsurfing, canoeing and sailing, fishing and scuba diving, while in their surroundings it is possible to go hiking, either on foot or by bicycle.[91] Lakeside noteworthy locations include Mergozzo, Cannero Riviera, Cannobio, Avigliana, Orta San Giulio, Torno, Bellano, Menaggio, Castellaro Lagusello, Tignale, Malcesine, Gardone Riviera, Molveno, Tenno, Ledro, Panicale, Bolsena, Nemi, Trevignano Romano, Civitella Alfedena and Gavoi.[92]

The Italian Lakes are provided with a navigation service by boats.[93][94] By boat on Lake Maggiore it is possible to visit the Borromean Islands, the Rocca Borromeo di Angera, Laveno Mombello, the Santa Caterina del Sasso and Luino, while on Lake Iseo it is possible to visit Monte Isola.[95] On Lake Como by boat it is possible to go to Como, Lecco, Varenna, Bellagio, Tremezzina, Menaggio and Cernobbio, while on Lake Garda it is possible to visit the Scaligero Castle and the Grottoes of Catullus of Sirmione, and the Vittoriale degli italiani of Salò.[95] Also on Lake Orta there is a navigation service, thanks to which it is possible to visit the San Giulio Island.[96]

International lake tourism in Italy has been able to establish due to the sounding board created by some celebrities of the international jet set, well known by the general public.[97] The purchase of a holiday residence along Lake Como by actor George Clooney was very publicized in 2001, as well as the marriage of Tom Cruise and Katie Holmes in 2006 in the Castello Orsini-Odescalchi, along Lake Bracciano.

Mountain tourism

[edit]

In Italy, there is both winter and summer mountain tourism. Despite a not particularly harsh climate compared to other countries located at more northern latitudes, Italy manages to attract tourists who practice winter sports due to the presence of numerous mountain ranges (the percentage of mountainous territory is around 35%).[99]

Among these are the Alps, the highest mountain range in Europe, and the Apennines, equipped with numerous winter sports and accommodation facilities. In the north the most famous ski resorts are in Sestriere, Livigno, Bormio, Ponte di Legno, in the Dolomites (especially Cortina d'Ampezzo), as well as in the Aosta Valley (especially Breuil-Cervinia), while in the center-south Abruzzo is the mountainous region with major ski resorts in Roccaraso, Ovindoli, Pescasseroli and Campo Felice.[100] These resort usually offer to turists, among others, a package known as Settimana bianca ('white week'), a week-long retreat during the winter season.

As for mountain summer tourism, noteworthy locations includes Courmayeur, Val di Fassa, Abetone and Ceresole Reale.[101] During the summer, in the Italian mountains, there are itineraries and paths, both on foot and by bicycle, where it is possible to admire naturalistic beauties, historic and artistic centres, glaciers, lakes, as well as practice numerous sports activities such as mountaineering, paragliding, rafting and hang gliding.[102] In the Italian mountains there are a large number of agritourism locations, baite and resorts, as well as hotels and restaurants.[103]

The volcanism of Italy is due chiefly to the presence, a short distance to the south, of the boundary between the Eurasian Plate and the African Plate. Italy is a volcanically active country, containing the only active volcanoes in mainland Europe (while volcanic islands are also present in Greece, in the volcanic arc of the southern Aegean). The active Italian volcanoes that attract tourists are Etna, Vesuvius and Stromboli, while the extinct Italian volcanoes that are most visited by tourists are Monte Vulture, Monte Amiata and Alban Hills.[104]

Hill tourism

[edit]

Italy has a predominantly hilly territory (equal to 41.6% of the total area).[99] The best known Italian hilly areas in the world are Langhe, Montferrat, Brianza, Berici Hills, Euganean Hills, Chianti, Colline Metallifere, Alban Hills, Gargano and Murge,[105] while notable locations include Erice, Civita di Bagnoregio, Maratea, Ravello, Urbino, Brisighella, Cortona, Asolo, Ostuni and Cervo.[106] The attraction of tourists to the Italian hills is mainly due to the mild climate, natural beauty and landscape, and historic and artistic centres, with agritourism, resorts, hotels and restaurants that are widespread in these territories.[107]

Vineyard Landscape of Piedmont: Langhe-Roero and Monferrato is a UNESCO World Heritage Site comprising "five distinct wine-growing areas with outstanding landscapes" plus the Castle of Grinzane Cavour in the region of Piedmont, Italy.[108] The site, which extends over hilly areas of Langhe and Montferrat, is one of the most important wine producing zones in Italy. Located in the centre of the Piedmont region (North-West of Italy), the site is inscribed as a "cultural landscape", since it is a result of the combined work of nature and man. The site is inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List thanks to the outstanding value of its wine culture, which has shaped the landscape over the centuries.[109] These sites are the result of a coexisting process between humans and the environment. As a result of its heartfelt attitude to the environment, this wine region has preserved an incredible cultural heritage that has become a model for other wine districts throughout the world.[110]

River and canal tourism

[edit]

Italian rivers and canals attract tourists, who can travel along them both in their navigable sections with houseboats and ships, and in non-navigable sections thanks to the use of canoes and kayaks.[111] Along the Italian rivers there are naturalistic beauties, villages and cities, historical monuments and pilgrimage routes.[112] Some Italian rivers such as the Ticino, the Orba, the Dora Baltea and the Elvo stream are frequented by tourists who try their hand as amateur gold prospectors, given the presence in the form of specks of this metal in the waters of these waterways.[113]

The most important Italian river that can be navigated is the Po, which with its 652 km (405 mi) in length is the longest river in Italy and which is navigable from Turin to the mouth.[111] Along the Po there are 12 ports, 111 berths (3 in Piedmont, 39 in Lombardy, 36 in Emilia-Romagna, 33 in Veneto) and about 20 river operators who provide boat rental services and organize excursions and river cruises.[111] Noteworthy is its delta mouth, which is one of the largest wetlands in Europe and the Mediterranean area, and which is rich in naturalistic beauties.[111] From the river Po it is possible to reach, directly or indirectly by sailing along its tributaries, the cities of Cremona, Mantua, Parma, Padua and Verona.[111]

The Brenta river is navigable from Padua to Venice, where it has its mouth.[111] Another noteworthy Italian river is the Sile, which is navigable from Treviso to the mouth, which is located near Jesolo.[111] Also important is the network of rivers and artificial canals are present between Friuli-Venezia Giulia and the Venetian Lagoon, which is formed by 109 km (68 mi) of navigable canals.[111] Also noteworthy is the Padana waterway, which connects Mantua to the sea via the Mincio river and the Po.[111]

As far as the navigable canals are concerned, worthy of note is the touristic navigation service of the Lombard Navigli, which is an urban transport network in the Milan area integrated by some lines of boats along these canals.[114] The tourist lines connect the dock of Milan with numerous comuni that rise along the Naviglio Grande up to Abbiategrasso and Turbigo.[114] Tourist navigation is also present along the Naviglio Martesana, in the stretch from Trezzo sull'Adda to Vaprio d'Adda.[114]

Underwater tourism

[edit]

The Marine Protected Areas of Italy restrict human activity for a conservation purpose, to protect natural resources or archaeological sites. There were twenty-seven such marine protected areas, and a further two "Submerged Archaeological Parks" (Italian: parchi sommersi); in 2018, two new marine protected areas were created. these areas help safeguard in total some 228,000 hectares (2,280 km2) of the seas around Italy as well as some 700 kilometres (430 mi) of its coastline, corresponding to 12% of the Italian coasts.[115]

Underwater tourism, both of a naturalistic type and linked to underwater archaeology, is also present.[116] For the naturalistic underwater type, noteworthy seaside locations include the Portofino Marine Protected Area (located between the municipalities of Camogli, Portofino and Santa Margherita Ligure), the island of Giglio, the island of Capraia, and the Maddalena archipelago.[116]

For the underwater archeology type, noteworthy seaside locations include Taormina, Capo Passero, Ustica, Noto, Marettimo, Marzamemi, Santa Maria di Castellabate, Baiae, Gaiola, Ischia, Campi Flegrei, Pantelleria, Syracuse, Gnatia, Tremiti Islands, Manduria and Isola di Capo Rizzuto.[116][117]

Notable Italian lakes that attract underwater tourism, both archaeological and naturalistic type, are Lake Iseo, Lake Como, Lake Garda, Lake Maggiore, Lake Idro, Lago di Levico, Lago di Lases, Lago di Tovel, Lago di Caldonazzo, Lago Grande and Lake of Capodacqua.[118][119][120][121][122]

Christmas, New Year's Eve and Easter tourism

[edit]

Christmas in Italy begins on 8 December, with the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, a public holiday in Italy and the day on which traditionally the Christmas tree is mounted and ends on 6 January, of the following year with the Epiphany.[123] 26 December (Saint Stephen's Day, in Italian Giorno di Santo Stefano), is also a public holiday. The tradition of the nativity scene comes from Italy. What is considered the first nativity scene in history (a living nativity scene) was set up by St. Francis Of Assisi in Greccio in 1223.[124] It seems that the first Christmas tree in Italy was erected at the Quirinal Palace at the behest of Queen Margherita, towards the end of the 19th century.[123] In Italy, the oldest Christmas market is considered to be that of Bologna, held for the first time in the 18th century and linked to the feast of Saint Lucy.[125]

Italy is among the countries most visited in the world by tourists during the Christmas holidays.[13] The attraction factors are the not too harsh climate, the cultural offer of the cities including museums, exhibitions and party initiatives, the rich gastronomy as well as the more affordable prices compared to other countries.[13] Italy is the second European country most visited by European tourists during the Christmas holidays behind Spain and ahead of Portugal, France and the United Kingdom.[13] The Italian cities most visited by international tourists during the Christmas holidays are, in order, Milan, Rome, Naples, Catania, Palermo and Cagliari.[13] Milan, in particular, is the favourite destination by European tourists for Germans, British and Portuguese tourists and the second for French, Spaniards and Dutch tourists.[13]

Easter in Italy (Italian: Pasqua) is one of the country's major holidays.[126] Easter in Italy enters Holy Week with Palm Sunday, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday and Holy Saturday, concluding with Easter Day and Easter Monday. Each day has a special significance. Italy is one of the most visited countries in the world during the Easter holidays.[127] Italy is the second European country most visited by international tourists during the Easter holidays behind Spain and ahead of France and Greece.[127] The Italian cities most visited by international tourists during the Easter holidays are, in order, Rome, Milan, Venice, Naples, Florence and Bologna.[127]

Shopping tourism

[edit]

Italy is also a destination for shopping tourism.[128] Italian fashion has a long tradition. The shops that attract the most tourists are those of clothing, leather goods and cosmetics and perfumery, while the most visited Italian cities for this type of tourism are, in descending order of visits, Milan, Florence, Rome, Venice and Turin.[129]

In Milan the most important shopping streets are Via Monte Napoleone, Via della Spiga, Via Manzoni, Corso Venezia, Via Sant'Andrea, Corso Vittorio Emanuele, Corso Buenos Aires, Corso di Porta Ticinese, Via Torino and Corso XXII Marzo,[130] while in Florence they are Via de' Tornabuoni, Via dei Calzaiuoli, Via del Corso, Mercato di San Lorenzo and Via Santo Spirito.[131]

In Rome the most important shopping streets are Via Condotti, Piazza di Spagna, Via del Babuino, Via Borgognona, Via Frattina, Via del Corso, Via del Campo Marzio, Via del Pellegrino, Via del Boschetto, Via Cola di Rienzo, Via del Governo Vecchio, Viale Guglielmo Marconi, Via Appia Nuova and Via Tuscolana,[132] while in Venice they are Le Mercerie, Piazza San Marco, Campo San Paolo, Burano and Murano.[133]

In Turin the most important shopping streets are Via Garibaldi, Contrada dei Guardinfanti, Galleria Subalpina, Via Roma, Piazza San Carlo a large number of visitors for, Piazza Carignano, Via Cesare Battisti, Piazza Carlo Alberto, Piazza Bodoni, Via Mazzini, Via Lagrange, Via Carlo Alberto, Piazza Carlo Felice, Via Po and Piazza Vittorio.[134]

Shopping tourism in Italy is also aimed at outlet stores. The outlets that attract the most tourists are located in Serravalle Scrivia, Castel San Pietro Romano, Barberino di Mugello, Noventa di Piave and Marcianise.[135]

Spa tourism

[edit]

Italy has one of the largest number of spas in the world,[136] and are appreciated internationally for the quality and effectiveness of the services and treatments offered.[137] This is also due to secondary volcanic phenomena that give rise to the emission of water, vapours and mud enriched by substances present in the Italian subsoil.[138]

Its origins are very remote, it is known that the ancient Greeks had already discovered its healing properties,[139] but the greatest admirers of antiquity were undoubtedly the ancient Romans who made it an aspect of their social life.[140]

The most renowned Italian spas are located in the localities of Abano Terme, Cortina d'Ampezzo, Bibione, Chianciano Terme, Montepulciano, Saturnia, Montecatini Terme, Contursi Terme, Castellammare di Stabia, Bagni San Filippo, Sirmione, Bormio, Viterbo, Pantelleria, Vulcano, Montegrotto Terme, Pescantina, Salsomaggiore Terme and Ischia.[141][142]

Wedding tourism

[edit]

Italy is the second-most popular destination in the world for wedding tourism after the Maldives and before Bali.[143] In 2022, 11,000 weddings were celebrated in Italy by foreign citizens who came to stay in the country to organize the wedding ceremony.[143] The length of stay of married couples and their guests to the ceremony is on average 3.3 nights.[143] In 2022, there were a total of 619,000 arrivals and over 2 million tourists connected to wedding tourism, with a turnover of around €599 million.[143] Italy hosts three of the top five European honeymoon destinations for wedding tourists: Positano, Rome and the Amalfi Coast.[143]

The Italian region chosen for marriage in Italy by foreign couples the most was Tuscany, with 21% of the total, followed by Lombardy, Campania, Apulia, Sicily, Lazio and Piedmont.[143][144]

In 2022, 57% of marriages celebrated in Italy by foreign couples were connected to spouses and guests from other European countries, while the main country of origin (29.2%) of foreign couples who decided to celebrate their wedding in Italy was the United States, followed by the United Kingdom, Germany and France.[143][144] Domestic wedding tourism is also noteworthy, given that in 2022 there were around 7,160 weddings of Italian couples celebrated in a region other than their own.[143]

Weddings of famous foreign couples include those between David Bowie and Iman Abdulmajid in Florence in the American church of San Giacomo, between Tom Cruise and Katie Holmes on Lake Bracciano, between George Clooney and Amal Alamuddin at Palazzo Papadopoli in Venice, between Kim Kardashian and Kanye West at Forte Belvedere in Florence and between Justin Timberlake and Jessica Biel at Borgo Egnazia in Apulia.[143]

Religious tourism

[edit]

There are numerous pilgrimage destinations in Italy, first of all Rome, the residence of the Pope (who is its bishop) and the seat of the Catholic Church. The city is a pilgrimage destination especially during the main events of Catholic religious life, especially during the Jubilees. Although his figure is not officially recognized by the faithful of other Christian denominations, the presence of the Pope in Rome also attracts others and is an important figure within the Christian creed.[145]

The Seven Pilgrim Churches of Rome are Basilica of St. John Lateran (Major Papal archbasilica), St. Peter's Basilica (Major Papal basilica), Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls (Major Papal basilica), Basilica of St. Mary Major (Major Papal basilica), Basilica of Saint Lawrence outside the Walls (Minor Papal basilica), Basilica of the Holy Cross in Jerusalem (Minor basilica), Sanctuary of Our Lady of Divine Love (Shrine).[146][147] In addition to the Holy See, there are numerous pilgrimage sites given by the presence of relics and remains of important figures linked to Christianity, rather than by the memory of events that have occurred that the faithful consider miraculous.[148]

Notable churches that are a destination for pilgrimages, in addition to St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, include Sanctuary of Saint Pio of Pietrelcina in San Giovanni Rotondo, Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi, Basilica della Santa Casa in Loreto, Shrine of the Virgin of the Rosary of Pompei, Basilica of Saint Anthony of Padua, Basilica santuario Madonna delle Lacrime in Syracuse, Church of St. Mary of Mount Berico in Vicenza, Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna and Sanctuary of the Madonna of San Luca in Bologna.[149]

The Via Francigena is an ancient road and pilgrimage route running from the cathedral city of Canterbury in England, through France and Switzerland, to Rome[150] and then to Apulia, Italy, where there were ports of embarkation for the Holy Land.[151] In medieval times it was an important road and pilgrimage route for those wishing to visit the Holy See and the tombs of the apostles Peter and Paul. Today the Via Francigena is travelled by pilgrims, especially in the last stretch of the road, the one in Italian territory.[149] Along the Via Francigena there are numerous places of worship such as sanctuaries, convents and churches that attract pilgrims and tourists, also for their artistic and architectural beauties.[149]

The Cammino Celeste ("Celestial Way") is also very popular with pilgrims.[149] It is a network of pilgrimage routes that connects the places of worship of Aquileia in Italy, Maria Saal in Austria and Brezje in Slovenia with the Sanctuary of Monte Lussari, located in the Julian Alps in the Italian municipality of Tarvisio, made official as an international pilgrimage route in the summer of 2006.[152] Its name derives from the union of the numerous places of ancient Marian devotion it passed through.[153]

Naturalistic tourism

[edit]

In Italy, there are several protected areas of various types: natural, mountain or marine parks, regional or local parks, and natural, wildlife or zoological reserves. In addition to this, there are numerous natural sites not necessarily protected by a park.

The parks of Italy include areas of land, sea, rivers and their banks, lakes and their environs which have environmental or naturalistic importance and are often valued for their landscape features and for representing particular local traditions. National parks of Italy cover about 5% of the country,[154] while the total area protected by national parks, regional parks of Italy and nature reserves covers about 10.5% of the Italian territory,[155] to which must be added 12% of coasts protected by Marine Protected Areas of Italy.[115]

Italy has one the highest levels of faunal biodiversity in Europe, with over 57,000 species recorded, representing more than a third of all European fauna.[156] The fauna of Italy includes 4,777 endemic animal species,[157] which include the Sardinian long-eared bat, Sardinian red deer, spectacled salamander, brown cave salamander, Italian newt, Italian frog, Apennine yellow-bellied toad, Italian wall lizard, Aeolian wall lizard, Sicilian wall lizard, Italian Aesculapian snake, and Sicilian pond turtle. In Italy there are 119 mammals species,[158] 550 bird species,[159] 69 reptile species,[160] 39 amphibian species,[161] 623 fish species[162] and 56,213 invertebrate species, of which 37,303 insect species.[163]

The flora of Italy was traditionally estimated to comprise about 5,500 vascular plant species.[164] However, as of 2005[update], 6,759 species are recorded in the Data bank of Italian vascular flora.[165] Italy has 1,371 endemic plant species and subspecies,[166] which include Sicilian Fir, Barbaricina columbine, Sea marigold, Lavender cotton and Ucriana violet.

Italy has many botanical gardens and historic gardens, some of which are known outside the country.[167][168] The Italian garden is stylistically based on symmetry, axial geometry and on the principle of imposing order over nature. It influenced the history of gardening, especially French gardens and English gardens.[169] The Italian garden was influenced by Roman gardens and Italian Renaissance gardens.

The Italian caves attract around 1.5 million tourists every year.[170] Main concentration of Italian caves is close to the Alps and the Apennins, principally due to karst.[171] Notable Italian caves are Castellana Caves, Frasassi Caves, Pertosa Cave, Giant Cave, Castelcivita Cave, Toirano Caves, Pastena Caves, Borgio Verezzi Caves, Grotto Calgeron, Grotta del Cavallone, Ear of Dionysius, Grotta del Gelo, Grotta di Ispinigoli, Paglicci Cave, Grotta dell'Addaura, Arene Candide, Castelcivita Caves, Fumane Cave, Neptune's Grotto, Nereo Cave, Pertosa Caves, Grotta dello Smeraldo and Blue Grotto.

Business tourism

[edit]

Business tourism enlivens entrances to the country and constitutes a fundamental part of the sector. Businessmen who travel to Italy also take advantage of their stay to visit the country.[172] This type includes those who use the accommodation facilities for business trips or to participate in events related to the production or marketing of various goods developed within the most disparate economic sectors. Businessmen who travel to Italy also take advantage of their stay to visit the country.[172] By way of example, some events that attract businessmen to Italy are reported:

- the Fiera Milano is a trade fair and exhibition organiser headquartered in Milan. The firm is the most important trade fair organiser in Italy and one of the largest in the world.[173]

- the Milan Motorcycle Show, one of the most important exhibitions in the world dedicated to motorcycles.[174]

- the Venice Film Festival is the oldest film festival in the world and one of the "Big Three" alongside Cannes and Berlin.[175][176]

- the Milan Furniture Fair is the most important showcase for the interiors and furnishings of the world.[177]

- the Milan Fashion Week, held twice a year, is one of the most important worldwide[178]

- the Genoa International Boat Show, one of the world's premier boat shows, held every year towards the end of September.[179]

- the Euroflora, held in Genoa every five years, is the most important floral festival in Europe.[180]

- the Terra Madre Salone del Gusto in Turin is an international gastronomy exhibition held every two years.

- the Turin International Book Fair is one of the largest book fairs in Europe.[181][182]

- the Lucca Comics & Games is an annual comic book and gaming convention in Lucca, the most important exhibition in Europe and second in the world after the Comiket in Tokyo.[183][184]

- the Vinitaly is an international wine competition and exposition that is held annually in April in Verona. VinItaly has been called the "most important convention of domestic and international wines"[185] and the "largest wine show in the world".[186][187]

- the Bologna Children's Book Fair is the leading professional fair for children's books in the world.[188] It is held yearly for four days in March or April in Bologna

- the Milano Monza Open-Air Motor Show is an annual auto show held in June 2021 in Milan and Monza, Italy.[189][190][191]

- the Concorso d'Eleganza Villa d'Este is a Concours d'Elegance event in Italy for classic and vintage cars. It takes place annually near the Villa d'Este hotel in Cernobbio, on the western shore of Lake Como. Since 2011, the event has taken place in the second half of May.

- the Genoa Science Festival is an annual science festival held in Genoa since 2003.[192] In 2006, the year in which it had 250,000 visits,[193] the Genoa Science Festival has been selected, the only Italian initiative, among the ten best events selected in 31 countries in the field of the promotion of culture scientific and technological at European level.[194]

- the Pitti Immagine is a collection of fashion industry events in Italy.[195] Pitti Immagine, is one of the world's most important platforms for men's clothing and accessory collections, and for launching new projects in men's fashion. It's held twice yearly in Florence, at the Fortezza da Basso.[196] The first edition of Pitti Immagine was held in Florence in September 1972.[197]

- the EuroChocolate is an annual chocolate festival that takes place in Perugia, the capital of the Umbria region in central Italy.[198] The festival has been held since 1993, and is one of the largest chocolate festivals in Europe.[199]

- the Giffoni Film Festival is one of the most well-known children's film festivals in the world.[200] It takes place in a small Italian town of Giffoni Valle Piana in Campania, close to Salerno and Naples. The Giffoni Film Festival has had a great impact in the history of entertainment and culture, not only in Italy, and it has developed a high reputation internationally.[201]

- the Ambrosetti Forum organized by The European House – Ambrosetti, a consulting firm – is an annual international economic conference held at Villa d'Este, in the Italian town of Cernobbio on the shores of Lake Como. Since its inception in 1975, the Forum has brought together heads of state, ministers, Nobel laureates and businesspeople to discuss current challenges to the world's economies and societies.[202][203]

Food and wine tourism

[edit]

Italian cuisine is one of the best known and most appreciated gastronomies worldwide.[204] Italian cuisine includes deeply rooted traditions common to the whole country, as well as all the regional gastronomies, different from each other, especially between the north and the south of Italy, which is in continuous exchange.[205][206][207] Many dishes that were once regional have proliferated with variations throughout the country.[208][209] Italian cuisine offers an abundance of taste, and is one of the most popular and copied around the world.[210] Italy is the world's largest producer of wine, as well as the country with the widest variety of indigenous grapevine varieties in the world.[211][212]

One of the main characteristics of Italian cuisine is its simplicity, with many dishes made up of few ingredients, and therefore Italian cooks often rely on the quality of the ingredients, rather than the complexity of preparation.[213][214] The most popular dishes and recipes, over the centuries, have often been created by ordinary people more so than by chefs, which is why many Italian recipes are suitable for home and daily cooking, respecting regional specificities, privileging only raw materials and ingredients from the region of origin of the dish and preserving its seasonality.[215][216][217]

Italian meal structure is typical of the European Mediterranean region and differs from North, Central, and Eastern European meal structure, though it still often consists of breakfast (colazione), lunch (pranzo), and supper (cena).[218] However, much less emphasis is placed on breakfast, and breakfast itself is often skipped or involves lighter meal portions than are seen in non-Mediterranean Western countries.[219] Late-morning and mid-afternoon snacks, called merenda (plural merende), are also often included in this meal structure.[220]

The Mediterranean diet forms the basis of Italian cuisine, rich in pasta, fish, fruits and vegetables.[221] Cheese, cold cuts and wine are central to Italian cuisine, and along with pizza and coffee (especially espresso) form part of Italian gastronomic culture.[222] Desserts have a long tradition of merging local flavours such as citrus fruits, pistachio and almonds with sweet cheeses like mascarpone and ricotta or exotic tastes as cocoa, vanilla and cinnamon. Gelato,[223] tiramisù[224] and cassata are among the most famous examples of Italian desserts, cakes and patisserie.

Italian cuisine relies heavily on traditional products; the country has a large number of traditional specialities protected under EU law.[225] From the 1950s onwards, a great variety of typical products of Italian cuisine have been recognized as PDO, PGI, TSG and GI by the Council of the European Union, to which they are added to the Indicazione geografica tipica (IGT), the regional Prodotto agroalimentare tradizionale (PAT) and the municipal Denominazione comunale d'origine (De.C.O.).[226][227] In the oenological field, there are specific legal protections: the Denominazione di origine controllata (DOC) and the Denominazione di origine controllata e garantita (DOCG).[228] Protected designation of origin (PDO) and Protected Geographical Indications (PGI) have also been established in olive growing.[229]

The cuisine is therefore often a reason for tourism in the peninsula, perhaps combined with one or more reasons previously described.[230] There are countless food festivals and fairs spread throughout the area, from small agricultural centres to large metropolises.[231] The hospitality sector is slowly updating by including cultural food and wine elements in its offer to tourists, both in traditional hotels and in specially created structures such as agritourisms.[232] In 2018 the food and wine expenditure by foreign tourists amounted to 9.23 billion euros, with an average expenditure of 117 euros each.[233]

Sports tourism

[edit]

Sport in Italy has a long tradition. In several sports, both individual and team, Italy has good representation and many successes. Football is the most popular sport in Italy.[235] Italy has won four FIFA World Cups championship (1934, 1938, 1982 and 2006), and is (along with Germany) currently the second most successful football team in World Cup history, after Brazil. Basketball, volleyball, and cycling are the next most popular/played sports, with Italy having a rich tradition in all three. Italy also has strong traditions in swimming, water polo, rugby union, tennis, athletics, fencing, and Formula One.

Tourism linked to sporting events is capable of attracting fans of various disciplines who, in several cases, then decide to stay to visit the country.[236] In addition to events of a global nature, capable of attracting a large number of visitors for a longer period of time (among the major ones the 1960 Summer Olympics, the 2006 Winter Olympics and the 1990 FIFA World Cup), minor events also contribute to the development of this factor of tourism, such as individual international matches of various sports (for example the home matches of Italy during the Six Nations Championship or the matches of clubs of various sports involved in continental competitions) or tournaments of more local importance.[237]

The Serie A is a professional league competition for football clubs located at the top of the Italian football league system and the winner is awarded the Scudetto and the Coppa Campioni d'Italia. Serie A is regarded as one of the best football leagues in the world and it is often depicted as the most tactical and defensively sound national league.[238] Serie A was the world's strongest national league in 2020 according to IFFHS,[239] and is ranked third among European leagues according to UEFA's league coefficient, behind La Liga and the Premier League and ahead of the Bundesliga and Ligue 1, which is based on the performance of Italian clubs in the Champions League and the Europa League during the previous five years. Serie A led the UEFA ranking from 1986 to 1988 and from 1990 to 1999.[240]

The Italian Grand Prix is the fifth oldest national Grand Prix (after the French Grand Prix, the American Grand Prize, the Spanish Grand Prix and the Russian Grand Prix), having been held since 1921. In 2013 it became the most-held Grand Prix (the 2021 edition was the 91st). It is one of the two Grands Prix (along with the British) which has run as an event of the Formula One World Championship Grands Prix every season, continuously since the championship was introduced in 1950. Every Formula One Italian Grand Prix in the World Championship era has been held at Monza except in 1980, when it was held at Imola.

The Giro d'Italia is an annual multiple-stage bicycle race primarily held in Italy, while also starting in, or passing through, other countries.[241] The first race was organized in 1909 to increase sales of the newspaper La Gazzetta dello Sport;[241][242] and is still run by a subsidiary of that paper's owner.[243][244] The Giro is a UCI World Tour event, which means that the teams that compete in the race are mostly UCI WorldTeams, with some additional teams invited as 'wild cards'.[245][246] Starting in 1909, the Giro d'Italia is the Grands Tours' second oldest.[234]

The Mille Miglia was an open-road, motorsport endurance race established in 1927 by the young Counts Francesco Mazzotti and Aymo Maggi, which took place in Italy twenty-four times from 1927 to 1957 (thirteen before World War II, eleven from 1947).[247] From 1953 until 1957, the Mille Miglia was also a round of the World Sports Car Championship. Since 1977, the "Mille Miglia" has been reborn as a regularity race for classic and vintage cars. Participation is limited to cars, produced no later than 1957, which had attended (or were registered to) the original race. The route (Brescia–Rome round trip) is similar to that of the original race, maintaining the point of departure/arrival in Viale Venezia in Brescia.

Traditions tourism

[edit]

Traditions of Italy are some set of traditions, beliefs, values, and customs that belongs within the culture of Italian people. These traditions have influenced life in Italy for centuries, and are still practised in our modern days.

Notable traditional Italian events that attract tourists are the celebrations of the Epiphany in Rome, the Festival of Saint Agatha of Catania, the Carnival of Venice, the Scoppio del carro in Florence, the Fish Festival of Camogli, the Infiorate di Spello, the Festival of Saint Rosalia of Palermo, the Notte della Taranta of Salento, the Chilli Festival of Diamante, the Grape Festival of Marino, the Christmas markets of Trentino-Alto Adige, the Nativity play of Sassi di Matera, the Battle of the Oranges of Ivrea, Almond Blossom Festival of Agrigento, Tulip Festival of Castiglione del Lago, May Day of Assisi, Festival of the Knot of Love of Valeggio sul Mincio, Medieval Festivals of Brisighella, Prosciutto di San Daniele Festival of San Daniele del Friuli, Festa del Redentore of Venice, Macchina di Santa Rosa of Viterbo, Rice Fair of Isola della Scala, Barcolana regatta of Trieste, Regatta of the Historical Marine Republics and Nougat Festival of Cremona.[248][249]

Traditional sports also attract tourists in Italy, such as the Palio, the name given in the country to an annual athletic contest, very often of a historical character, pitting the neighbourhoods of a town or the hamlets of a comune against each other. Typically, they are fought in costume and commemorate some event or tradition of the Middle Ages and thus often involve horse racing, archery, jousting, crossbow shooting, and similar medieval sports.[250] The Palio di Siena is the only one that has been run without interruption since it started in the 1630s and is definitely the most famous all over the world,[251] attracting tourists from every continent.[252]

Another traditional Italian sport that attracts tourists is the Calcio Fiorentino (also referred to as calcio storico, "historic football"), an early form of football (soccer and rugby) that originated during the Middle Ages and is still played annually today in the Piazza Santa Croce in Florence.[253][254] Other important Italian traditional competitions that attract tourists are the Palio di Asti, the Palio di Legnano, the Palio di Ferrara, the Giostra del Saracino and the Giostra della Quintana.[255]

UNESCO World Heritage Sites tourism

[edit]

Italy is the country with the highest concentration in the world of the UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[256][19] As of 2021[update], Italy has a total of 58 inscribed sites, making it the country with the most World Heritage Sites just above China (56).[256][19] Out of Italy's 58 heritage sites, 53 are cultural and 5 are natural.[19] 50% of the tourists who visit the UNESCO heritage sites in Italy are foreigners, and of these, 75% are in Italy for a cultural holiday.[257]

Among the most famous Italian UNESCO World Heritage Sites there are Sassi di Matera; Porto Venere, Palmaria, Tino, Tinetto and Cinque Terre; Val d'Orcia; Early Christian Monuments of Ravenna; Valle dei Templi; Alberobello; Etruscan Necropolises of Cerveteri and Tarquinia; Pompeii, Torre Annunziata and Herculaneum; Palmanova; Barumini nuraghes; Dolomites; Santa Maria delle Grazie and The Last Supper; Castel del Monte; Royal Palace of Caserta, Aqueduct of Vanvitelli and San Leucio Complex; Syracuse and Necropolis of Pantalica; Villa d'Este; Langhe-Roero and Montferrat; Aeolian Islands; Val di Noto; Amalfi Coast; Rhaetian Railway in the Albula/Bernina Landscapes; Aquileia; Duomo and the Leaning Tower of Pisa; Arab-Norman Palermo and the Cathedral Churches of Cefalù and Monreale; Residences of the Royal House of Savoy; Parco Nazionale del Cilento, Vallo di Diano e Alburni, Paestum, Velia and Certosa di Padula; Scrovegni Chapel.[258][259][260]

Historical and artistic villages tourism

[edit]

The historical and artistic Italian villages are attracting an increasing number of tourists.[261] A non-profit private association of small Italian towns of strong historical and artistic interest[262] named I Borghi più belli d'Italia (English: The most beautiful Villages of Italy) and affiliated to the international association The Most Beautiful Villages in the World, was created in 2001 on the initiative of the Tourism Council of the National Association of Italian Municipalities[263] with the aim of preserving and maintaining villages of quality heritage.[263] Founded to contribute to safeguarding, conserving and revitalizing small villages and municipalities, but sometimes even individual hamlets, which, being outside the main tourist circuits, they risk, despite their great value, being forgotten with consequent degradation, depopulation and abandonment.[264] Its motto is Il fascino dell'Italia nascosta ("The charm of hidden Italy").[265]

As of November 2023, 361 villages in Italy have been listed in "The Most Beautiful Villages of Italy".[266] This association organizes initiatives within the villages, such as festivals, exhibitions, fetes, conferences and concerts that highlight the cultural, historical, gastronomic and linguistic heritage, involving residents, schools, and local artists.[267] The club promotes numerous initiatives on the international market.[268][269][270][271][272][273] In 2016, the association signed a global agreement with ENIT,[274] to promote tourism in the most beautiful villages in the world.[275] In 2017, the club signed an agreement with Costa Cruises[276] for the enhancement of some villages, which are offered to cruise passengers arriving in Italian ports aboard the operator's ships.[277]

The Bandiera arancione is a tourist-environmental quality recognition conferred by the Touring Club Italiano (TCI) to small towns in the Italian hinterland (maximum 15,000 inhabitants) which stand out for their quality hospitality.[278] The idea was born in 1998 in Sassello (in Liguria), from the need of the regional body to promote and enhance the hinterland.[279] The TCI, therefore, developed an analysis model (called territorial analysis model or MAT) to identify the first deserving localities.[280] Subsequently, the recognition was promoted on a national scale, identifying small places of excellence in each region.[280] The group, as of June 2021, includes 252 villages.[281] The project is the only Italian one included by the World Tourism Organization among the programs successfully implemented for the sustainable development of tourism worldwide.[282]

Tourist railways

[edit]

In Italy the heritage railway institute is recognized and protected by law no. 128 of 9 August 2017, which has as its objective the protection and valorisation of disused, suspended or abolished railway lines, of particular cultural, landscape and tourist value, including both railway routes and stations and the related works of art and appurtenances, on which, upon proposal of the regions to which they belong, tourism-type traffic management is applied (art. 2, paragraph 1).[283] At the same time, the law identified a first list of 18 tourist railways, considered to be of particular value (art. 2, paragraph 2).[283]

The list is periodically updated by decree of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport, in agreement with the Ministry of Economy and Finance and the Ministry of Culture, also taking into account the reports in the State-Regions Conference, a list which in 2022 reached 26 railway lines.[284] According to article 1, law 128/2017 has as its purpose: "the protection and valorisation of railway sections of particular cultural, landscape and tourist value, which include railway routes, stations and related works of art and appurtenances, and of the historic and tourist rolling stock authorized to travel along them, as well as the regulation of the use of ferrocycles".[283]

In July 2023, Ferrovie dello Stato established a new company, the "FS Treni Turistici Italiani" (English: FS Italian Tourist Trains), with the mission "to propose an offer of railway services expressly designed and calibrated for quality, sustainable tourism and attentive to rediscovering the riches of the Italian territory. Tourism that can experience the train journey as an integral moment of the holiday, an element of quality in the overall tourist experience".[285] There are three service areas proposed: Luxury trains, Express and historic trains, and Regional trains.[285]

Nightlife tourism

[edit]

The nightlife in Italy is attractive to both tourists and locals. Italy is known to have some of the best nightlife in the world.[287] The best known Italian destinations for nightlife are:[287]

- Milan (Lombardy), in particular Navigli, Brera, Isola, Porta Romana, Lambrate, Idroscalo, Corso Como, Corso Sempione and Colonne di San Lorenzo;[288]

- Florence (Tuscany), in particular, the neighbourhoods of Oltrarno, Santo Spirito and Santa Croce;

- Rome (Lazio), in particular, the neighbourhoods of Trastevere, Pigneto, San Lorenzo and Ostiense;

- Venice (Veneto), in particular, the neighbourhoods of Erbaria, Fondamenta Misericordia and Santa Margherita;

- Salento (Apulia), in particular Gallipoli, Otranto and Lecce;

- Riviera of Romagna (Emilia-Romagna), in particular Riccione, Rimini and Milano Marittima;

- Jesolo (Veneto);

- Riviera del Corallo (Sardinia), in particular Alghero;

- Ischia (Campania);

- Coast of the Gods (Calabria), in particular Tropea, Capo Vaticano and Scilla.

LGBT tourism

[edit]

Italy represented one of the main homosexual male tourist destinations between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century.[289] In fact, in Italy there were no anti-homosexual laws, which were widespread in the countries of Northern Europe, such as the German paragraph 175 or the sentences suffered by Oscar Wilde in the United Kingdom.[289] Places such as Capri, Taormina, Florence, Venice, Rome and Naples were the favourite places of homosexual tourism of the time.[289]

This type of tourism disappeared in Italy in the 1950s due to changed political and social conditions, which favoured other types of tourism, such as "family" tourism.[289] As a consequence, other Mediterranean cities (such as Mykonos, Ibiza and Sitges) took the place of the Italian ones for LGBT tourism.[289]

Today LGBT tourism in Italy is mainly an urban phenomenon, such as in Milan and Rome due to the high variety of discos, pubs, bars, cruising, saunas, B&B, restaurants, which meet all needs. of the nightlife.[290][291] In summer, however, the first Italian gay resort is Gallipoli which, with bars, discos, B&B and beaches, attracts people from all over Italy and abroad, taking away the primacy of Versilia.[292] The naturist beaches of Spiaggia D'Ayala, Campomarino di Maruggio, Torre Guaceto and Brindisi attract LGBT crowds from all over the world.[293]

Luxury tourism

[edit]

Luxury tourism in Italy is highly developed, corresponding to €25 billion (in particular €2 billion for catering and €14 billion for visits, excursions and shopping), a figure that increases, also considering the related activities and the indirect expenses of luxury tourists, to €60 billion, which corresponds to 3% of Italy's GDP.[294]

The companies operating in the luxury tourism sector in Italy are 1% of the accommodation businesses present in the country, corresponding to approximately 3% of the nights spent in Italian accommodation facilities, but generate 25% of the total expenditure of tourists who choose Italy as their destination, and 15% of the total turnover of accommodation facilities.[294] These data can be explained by considering some characteristics of luxury tourism where these tourists who travel to Italy spend nine times more than the average, and the most expensive hotels employ twice as many employees as an average quality hotel.[294]

Regarding luxury tourism, Italy ranks 1st in the world for artistic-cultural tourism and food and wine tourism, 2nd place for mountain tourism and tourism in large cities and 4th place for seaside tourism.[294] As for the most popular destinations for luxury tourists in Italy, in mountain tourism are the Dolomites, especially Cortina d'Ampezzo and Madonna di Campiglio, Trentino-Alto Adige, especially Selva di Val Gardena, and Aosta Valley, in particular Courmayeur, for lake tourism Lake Como and Lake Garda, in particular Gardone Riviera, while for seaside tourism the Cinque Terre and Portofino, the Amalfi Coast, in particular Amalfi, Ravello and Positano, the island of Capri, the Costa Smeralda (especially Porto Cervo), Porto Ercole, Forte dei Marmi, Santa Margherita Ligure and Taormina.[295][296][297] As for the Italian cities, the most visited by luxury tourists are Venice, Milan, Florence and Rome.[295]

In particular, Costa Smeralda is the most expensive location in Europe. House prices reach up to €300,000 ($392,200) per square metre.[298][299][300] Development of the Costa Smeralda started in 1961 and was financed by a consortium of companies led by Prince Karim Aga Khan. Spiaggia del Principe, one of the beaches along the Costa Smeralda, was named after this Ishmaelite prince.[301]

Amusement and theme park tourism

[edit]

The most visited amusement park in Italy is Gardaland, with 3 million visitors per year (2019).[302] Located in Castelnuovo del Garda, is adjacent to Lake Garda. The entire complex covers an area of 445,000 m2 (4,789,940 sq ft), while the theme park alone measures 200,000 m2 (2,152,782 sq ft).[302] Gardaland is the eighth in Europe by the number of amusement park visitors (2019).[302] In June 2005 Gardaland ranked fifth in the Forbes ranking of the top ten best amusement parks in the world.[303]

The second most visited Italian amusement park is Mirabilandia, with 2 million annual visitors (2019).[302] Located in Savio, a frazione of Ravenna, with a total area of 850,000 m2 (9,149,324 sq ft) it is the biggest amusement park in Italy.[304] Other popular Italian amusement/theme parks are Cinecittà World in Rome, Zoomarine in Torvaianica, Cavallino Matto in Marina di Castagneto Carducci, Italia in miniatura in Rimini, Cowboyland in Voghera, Pombia Safari Park in Pombia, Aquarium of Genoa, Parco Natura Viva in Bussolengo, Zoom Torino in Cumiana and Le Cornelle in Valbrembo.

Roots tourism

[edit]

Italy has experienced a conspicuous emigration to foreign countries following Italian unification, World War I and World War II. By 1980, it was estimated that about 25,000,000 Italians were residing outside Italy.[305] It is estimated that the number of their descendants, who are called "oriundi", is about 80 million worldwide.[306]