Vellum

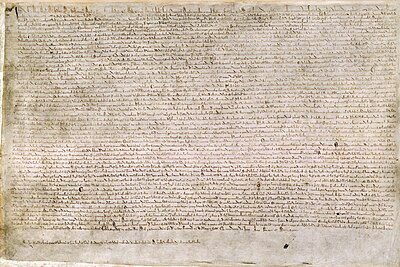

Vellum is prepared animal skin or membrane, typically used as writing material. It is often distinguished from parchment, either by being made from calfskin (rather than the skin of other animals),[1] or simply by being of a higher quality.[2] Vellum is prepared for writing and printing on single pages, scrolls, and codices (books).

Modern scholars and experts often prefer to use the broader term "membrane", which avoids the need to draw a distinction between vellum and parchment.[2][3]: 9–10 It may be very hard to determine the animal species involved (let alone its age) without detailed scientific analysis.[4]

Vellum is generally smooth and durable, but there are great variations in its texture which are affected by the way it is made and the quality of the skin. The making involves the cleaning, bleaching, stretching on a frame (a "herse"), and scraping of the skin with a crescent-shaped knife (a "lunarium" or "lunellum"). To create tension, the process goes back and forth between scraping, wetting and drying. Scratching the surface with pumice, and treating with lime or chalk to make it suitable for writing or printing ink can create a final look.[1]

Modern "paper vellum" is made of plant cellulose fibers and gets its name from its similar usage to actual vellum, as well as its high quality. It is used for a variety of purposes including tracing, technical drawings, plans and blueprints. Tracing paper is essentially the same thing, however the quality level differs, sometimes greatly. [5][6][7]

Terminology

[edit]

Though Christopher de Hamel, an expert on medieval manuscripts, writes that "for most purposes the words parchment and vellum are interchangeable",[8] a number of distinctions have been made in the past and present.

The word "vellum" is borrowed from Old French vélin 'calfskin', derived in turn from the Latin word vitulinum 'made from calf'.[9] However, in Europe, from Roman times, the word was used for the best quality of prepared skin, regardless of the animal from which the hide was obtained. Calf, sheep, and goat were all commonly used, and other animals, including pig, deer, donkey, horse, or camel were used on occasion. The best quality, "uterine vellum",[10] was said to be made from the skins of stillborn or unborn animals, although the term was also applied to fine quality skins made from young animals.[2] However, there has long been much blurring of the boundaries between these terms. In 1519, William Horman could write in his Vulgaria: "That stouffe that we wrytte upon, and is made of beestis skynnes, is somtyme called parchement, somtyme velem, somtyme abortyve, somtyme membraan."[11] Writing in 1936, Lee Ustick explained that:

To-day the distinction, among collectors of manuscripts, is that vellum is a highly refined form of skin, parchment a cruder form, usually thick, harsh, less highly polished than vellum, but with no distinction between skin of calf, or sheep, or of goat.[12]

French sources, closer to the original etymology, tend to define velin as from calf only, while the British Standards Institution defines parchment as made from the split skin of several species, and vellum from the unsplit skin.[13] In the usage of modern practitioners of the artistic crafts of writing, illuminating, lettering, and bookbinding, "vellum" is normally reserved for calfskin, while any other skin is called "parchment".[14]

Manufacture

[edit]

Vellum allows some light to pass through it. It is made from the skin of a young animal. The skin is washed with water and lime (calcium hydroxide), and then soaked in lime for several days to soften and remove the hair.[15] Once clear, the two sides of the skin are distinct: the body side and the hairy side. The "inside body side" of the skin is usually the lighter and more refined of the two. The hair follicles may be visible on the outer side, together with any scars from when the animal was alive. The membrane can also show the pattern of the animal's vein network called the "veining" of the sheet.[16]

The makers remove any remaining hair ("scudding") and dry the skin by attaching it to a frame (a "herse").[3]: 11 They attach the skin at points around the edge with cords and wrap the part next to these points around a pebble (a "pippin").[3]: 11 They then use a crescent shaped knife, (a "lunarium" or "lunellum"), to clean off any remaining hairs.

The makers thoroughly clean the skin and process it into sheets once it is completely dry. They can extract many sheets from the piece of skin. The number of sheets depends on the size of the skin and the required length and breadth of each individual sheet. For example, the average calfskin could provide roughly three and a half medium sheets of writing material. The makers can double it when they fold the skin into two conjoined leaves, also known as a bifolium. Historians have found evidence of manuscripts where the scribe wrote down the medieval instructions now followed by modern membrane makers.[17] The makers rubbed them with a round, flat object ("pouncing") to ensure that the ink would adhere to the surface.[16] Even so, ink would gradually flake off of the membrane, especially if it was used in a scroll that was frequently rolled and unrolled.

Manuscripts

[edit]

Preparing manuscripts

[edit]Once the vellum is prepared, traditionally a quire is formed of a group of several sheets. Raymond Clemens and Timothy Graham point out, in their Introduction to Manuscript Studies, that "the quire was the scribe's basic writing unit throughout the Middle Ages".[3]: 14 Guidelines are then made on the membrane. They note "'pricking' is the process of making holes in a sheet of parchment (or membrane) in preparation of its ruling. The lines were then made by ruling between the prick marks ...The process of entering ruled lines on the page to serve as a guide for entering text. Most manuscripts were ruled with horizontal lines that served as the baselines on which the text was entered and with vertical bounding lines that marked the boundaries of the columns".[3]: 15–17

Usage

[edit]Most of the finer sort of medieval manuscripts, whether illuminated or not, were written on vellum. Some Gandhāran Buddhist texts were written on vellum, and all Sifrei Torah (Hebrew: ספר תורה Sefer Torah; plural: ספרי תורה, Sifrei Torah) are written on kosher klaf or vellum.

A quarter of the 180-copy edition of Johannes Gutenberg's first Bible printed in 1455 with movable type was also printed on vellum, presumably because his market expected this for a high-quality book. Paper was used for most book-printing, as it was cheaper and easier to process through a printing press and to bind. The twelfth-century Winchester Bible was also written on approximately 250 calfskins.

In art, vellum was used for paintings, especially if they needed to be sent long distances, before canvas became widely used in about 1500, and continued to be used for drawings, and watercolours. Old master prints were sometimes printed on vellum, especially for presentation copies, until at least the seventeenth century.

Limp vellum or limp-parchment bindings were used frequently in the 16th and 17th centuries, and were sometimes gilt but were also often not embellished. In later centuries vellum has been more commonly used like leather, that is, as the covering for stiff board bindings. Vellum can be stained virtually any color but seldom is, as a great part of its beauty and appeal rests in its faint grain and hair markings, as well as its warmth and simplicity.

Lasting in excess of 1,000 years—for example, Pastoral Care (Troyes, Bibliothèque Municipale, MS 504), dates from about 600 and is in excellent condition—animal vellum can be far more durable than paper. For this reason, many important documents are written on animal vellum, such as diplomas. Referring to a diploma as a "sheepskin" alludes to the time when diplomas were written on vellum made from animal hides.

Modern usage

[edit]British Acts of Parliament are still printed on vellum for archival purposes,[18] as are those of the Republic of Ireland.[19] In February 2016, the UK House of Lords announced that legislation would be printed on archival paper instead of the traditional vellum from April 2016.[20] However, Cabinet Office Minister Matthew Hancock intervened by agreeing to fund the continued use of vellum from the Cabinet Office budget.[21] On 2017, the House of Commons Commission agreed that it would provide front and back vellum covers for record copies of Acts.[22]

Today, because of low demand and complicated manufacturing process, animal vellum is expensive and hard to find.[23] The only UK company still producing traditional parchment and vellum is William Cowley (established 1870), which is based in Newport Pagnell, Buckinghamshire. A modern imitation is made of cotton. Known as paper vellum, this material is considerably cheaper than animal vellum and can be found in most art and drafting supply stores. Some brands of writing paper and other sorts of paper use the term "vellum" to suggest quality.

Vellum is still used for Jewish scrolls, of the Torah in particular, for luxury bookbinding, memorial books, and for various documents in calligraphy. It is also used on instruments such as the banjo and the bodhran, although synthetic skins are available for these instruments and have become more commonly used.

The Catholic Church still issues its decrees and diplomas for its officials on vellum.

Paper vellum

[edit]Modern imitation vellum is made from plasticized rag cotton or fibers from interior tree bark. Terms include: paper vellum, Japanese vellum, and vegetable vellum.[7][6] Paper vellum is usually translucent and its various sizes are often used in applications where tracing is required, such as architectural plans. Its dimensions are more stable than a linen or paper sheet, which is frequently critical in the development of large scaled drawings such as blueprints. Paper vellum has also become extremely important in hand or chemical reproduction technology for dissemination of plan copies. Like a high-quality traditional vellum, paper vellum could be produced thin enough to be virtually transparent to strong light, enabling a source drawing to be used directly in the reproduction of field-used drawings.[24]

Preservation

[edit]Vellum is ideally stored in a stable environment with constant temperature and 30% (± 5%) relative humidity. If vellum is stored in an environment with less than 11% relative humidity, it becomes fragile, and vulnerable to mechanical stresses. However, if it is stored in an environment with greater than 40% relative humidity, it becomes vulnerable to gelation and to mould or fungus growth.[25] The optimal relative humidity for proper storage of vellum does not overlap that of paper, which poses a challenge for libraries.[26] The optimal temperature for the keeping of vellum is approximately 20 °C (68 °F).[27]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "Differences between Parchment, Vellum and Paper". archives.gov. Retrieved 2016-06-16.

- ^ a b c Stokes, Roy Bishop; Esdaile, Arundell James Kennedy (2001). Almagno, Stephen R. (ed.). Esdaile's manual of bibliography (6 ed.). Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-8108-3922-9.

- ^ a b c d e Clemens, Raymond; Graham, Timothy (2007). Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3863-9.

- ^ Cains, Anthony (1994). "The surface examination of skin: a binder's note on the identification of animal species used in the making of parchment". In O'Mahony, Felicity (ed.). The Book of Kells: proceedings of a conference at Trinity College Dublin, 6–9 September 1992. Aldershot: Scolar Press. pp. 172–4. ISBN 0-85967-967-5.

- ^ Hepler, Wallach & Hepler 2012, pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b "Japanese vellum - CAMEO". cameo.mfa.org. Archived from the original on 2017-09-03. Retrieved 2017-09-03.

- ^ a b "How Modern Day Vellum Stationery Is Produced". The Note Pad | Stationery & Party Etiquette Blog by American Stationery. 2011-07-04. Archived from the original on 2017-09-03. Retrieved 2017-09-03.

- ^ Christopher de Hamel, Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts: Twelve Journeys into the Medieval World, London, Allen Lane, 2016, Introduction, (ISBN 978-0241003046), google books

- ^ "vellum". Online Etymological Dictionary. Retrieved 2014-08-09.

- ^ Houston, Keith (2016). The Book: A Cover-to-Cover Exploration of the Most Powerful Object of Our Time. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-24479-3. Archived from the original on 2016-12-02. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ William Horman, Vulgaria (1519), fol. 80v; cited in Ustick 1936, p. 440.

- ^ Ustick 1936, p. 440.

- ^ Young, Laura, A., Bookbinding & conservation by hand: a working guide, Oak Knoll Press, 1995, ISBN 1-884718-11-6, ISBN 978-1-884718-11-3, Google books Archived 2017-01-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Johnston, E. (1906 et seq.) Writing, Illuminating, and Lettering; Lamb, C.M. (ed.)(1956) The Calligrapher's Handbook; and publications of Society of Scribes & Illuminators

- ^ "The Making of a Medieval Book". The J. Paul Getty Trust. Archived from the original on 2010-11-25. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ a b ""Recording the physical features of Codex Sinaiticus". Codex Sinaiticus, in partnership with the British Library". Archived from the original on 2012-05-01. Retrieved 2012-04-02.

- ^ Thompson, Daniel. "Medieval Parchment-Making". The Library 16, no. 4 (1935).

- ^ "Goat skin tradition wins the day". BBC News Online. 1999-11-02. Archived from the original on 2008-04-09. Retrieved 2016-02-11.

Acts of Parliament dating back to 1497 recorded on vellum are currently held in the House of Lords Public Record Office

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions about the Houses of the Oireachtas - Tithe an Oireachtais". Oireachtas. Archived from the original on 2012-03-28. Retrieved 2016-02-11.

Once a Bill has been passed by both Houses, the Taoiseach presents a vellum copy of the Bill, prepared in the Office of the Houses of the Oireachtas to the President for signature and promulgation as law.

- ^ Hughes, Laura (2016-02-09). "Thousand year old tradition of printing Britain's laws on vellum has been scrapped to save just £80,000". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2016-02-12. Retrieved 2016-02-11.

- ^ Hughes, Laura (2016-02-14). "Vellum should be saved in a bid to 'safeguard our great traditions', says minister". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2016-02-13. Retrieved 2016-02-15.

Mr Hancock told The Daily Telegraph: 'Recording our laws on vellum is a millennium long tradition, and surprisingly cost effective. While the world around us constantly changes, we should safeguard some of our great traditions and not let the use of vellum die out.'

- ^ "Vellum: printing record copies of public Acts". House of Commons Library. 15 August 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ "Nowhere to hide: the value of vellum". ICLR. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ Drafting, 60–61; Yee, Rendow, Architectural Drawing: A Visual Compendium of Types and Methods, 4th edition, 2012, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 1118310446, 781118310441, google

- ^ Eric F. Hansen and Steve N. Lee, "The Effects of Relative Humidity on Some Physical Properties of Modern Vellum: Implications for the Optimum Relative Humidity for the Display and Storage of Parchment", The Book and Paper Group Annual (1991).

- ^ "Parchment/Vellum: Cold Storage - Research Projects - Preservation Science (Preservation, Library of Congress)". www.loc.gov. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- ^ "Tips on Caring for Works on Parchment" (PDF). Iowa Conservation And Preservation Consortium. Retrieved 2023-04-01.

References

[edit]- Hepler, Dana J.; Wallach, Paul Ross; Hepler, Donald (2012). Drafting and Design for Architecture & Construction (9th ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1111128135.

- Hingley, Mark (2001). "Success in the Treatment of Parchment and Vellum using a Suction Table". Journal of the Society of Archivists. 22 (1): 71–77. doi:10.1080/00379810120037513. S2CID 110087014.

- Ustick, W. Lee (1936). "'Parchment' and 'vellum'". The Library. 4th ser. 16 (4): 439–43. doi:10.1093/library/s4-XVI.4.439.

- Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books a Living History. Thames & Hudson. pp. 22, 43, 57. ISBN 978-0-500-29115-3.

External links

[edit]- On-line demonstration of the preparation of vellum from the BNF, Paris—text in French, but mostly visual.