Sammy Gravano

Sammy Gravano | |

|---|---|

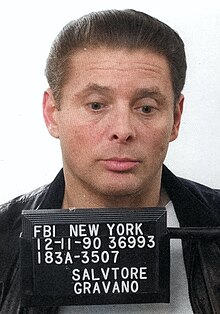

Gravano's 1990 mugshot | |

| Born | Salvatore Gravano March 12, 1945 Brooklyn, New York, U.S. |

| Other names | "Sammy the Bull" ”The little guy” Jimmy Moran (WITSEC alias) |

| Occupation(s) | Mobster YouTuber |

| Spouse |

Debra Scibetta

(m. 1971; div. 1992) |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives | Nicholas Scibetta (brother-in-law) Eddie Garafola (brother-in-law) |

| Allegiance | Gambino crime family |

| Conviction(s) | Drug trafficking (2002) |

| Criminal penalty | Five years' imprisonment (1994, leniency due to testimony) 20 years' and 19 years' imprisonment to run concurrently (2002) |

YouTube information | |

| Channel | |

| Years active | 2020–present |

| Subscribers | 607,234[1] |

| Total views | 119 million[1] |

Last updated: November 20th, 2023 | |

| Website | Official website |

Salvatore "Sammy the Bull" Gravano (born March 12, 1945) is an American former mobster who rose to the position of underboss in the Gambino crime family. As the underboss, Gravano played a major role in prosecuting John Gotti, the crime family's boss, by agreeing to testify as a government witness against him and other mobsters in a deal in which he confessed to involvement in 19 murders.[2]

Originally an associate for the Colombo crime family, and later for the Brooklyn faction of the Gambino family, Gravano was part of the group in 1985 that conspired to murder Gambino boss Paul Castellano. Gravano played a key role in planning and executing Castellano's murder, along with John Gotti, Angelo Ruggiero, Frank DeCicco, and Joseph Armone.

Soon after Castellano's murder, Gotti elevated Gravano to become an official captain after Salvatore "Toddo" Aurelio stepped down, a position Gravano held until 1987 when he became consigliere. In 1988, he became underboss, a position he held at the time he became a government witness. In 1991, Gravano agreed to turn state's evidence and testify for the prosecution against Gotti after hearing the boss making several disparaging and untrue remarks about Gravano on a wiretap that implicated them both in several murders.

At the time, Gravano was among the highest-ranking members of the Five Families, but broke his blood oath and cooperated with the government. As a result of his testimonies, Gotti and Frank LoCascio were sentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole in 1992. In 1994, a federal judge sentenced Gravano to five years in prison; however, since Gravano had already served four years, the sentence amounted to less than one year. He was released early and entered the U.S. federal Witness Protection Program in Colorado, but left the program in 1995 after eight months and moved to Arizona with his family.

In 1997, Gravano was consulted several times for the biographical book about his life, Underboss by author Peter Maas. In February 2000, Gravano and nearly 40 other ring members—including his ex-wife Debra, daughter Karen and son Gerard—were arrested on federal and state drug charges.

In 2001, Gravano and his son, Gerard, were indicted on mirror charges with the federal government. In 2002, Gravano was sentenced in New York to twenty years in prison. A month later, he was also sentenced in Arizona to nineteen years in prison to run concurrently. Additionally, Gravano was sentenced to lifetime supervised release and a $100,000 fine. He was released in September 2017.

Childhood and early life

[edit]Salvatore Gravano was born on March 12, 1945, in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, to Giorlando "Gerry" and Caterina "Kay" Gravano.[3] He was the youngest of five children, having two older sisters and two siblings who died before he was born. Both of Gravano's parents hailed from Sicily. Sammy's mother, Caterina, born in 1906, arrived in the United States as a young girl from Puglia, Italy. While his father, Giorlando, born in 1901, arrived in the US after jumping ship in Canada and, with help from his older brother Alphonsio Gravano, was smuggled into the US illegally. Alphonsio was already an established bootlegger and made member of the Sicilian mafia. During Prohibition, Alphonsio was a successful bootlegger and transported booze into the US on both North East and North West coasts.

As part of the Sunset Fleet, Alphonsio ran booze through the Hudson River and other New York waterways. His booze made its way into the city to the Fulton Fish Market and then sold to the NY speakeasies. On the West coast his operation ran the booze from Canada to Oregon, near the Bull River. Gerry worked as a skilled fisherman in Sicily. In the US, he became a painter, working on houses and buildings, as New York grew at a staggering rate. Later, Gravano's parents ran a small dress factory, his mother being a talented seamstress. They maintained a good standard of living for the family.[3] Early on, one of Gravano's relatives remarked that he looked like his uncle Sammy. From that point on, everyone called Gravano "Little Sammy" instead of "Salvatore" or "Sal".[3]

At age 13, Gravano joined the Rampers, a prominent street gang in Bensonhurst. He found that some older children had stolen his bicycle and went to fight the thieves. Made men who were watching from a café, saw him take on a few of the older boys at once and they gave Gravano back his bike. As he was leaving, one of the made men remarked on how little Sammy fought "like a bull", hence his nickname "The Bull".[4]

Gravano had dyslexia, was bullied, and did poorly in school.[5] Teachers classified him as "a slow learner". He was held back from grade advancement on two occasions, the 4th and 7th grades, and also punched school officials on two occasions.[5] Gravano was eventually sent to a school for "incorrigibles" (600 school); however, just before he reached the age of 16, the school refused to keep him any longer and his parents signed him out of school.[5] Gravano's father tried to redirect and discipline his son, including forcing him to attend Mass, but had little success.[6]

In 1964, Gravano was drafted into the United States Army and served in Fort Jackson, South Carolina. While an enlisted man, Gravano worked as a mess hall cook. He rose to the rank of corporal and was granted an honorable discharge after two years.[5]

In 1971, Gravano married Debra Scibetta; they had two children.[7] His daughter Karen Gravano appeared on the VH1 reality series Mob Wives beginning in 2011,[5] and released a book in 2013 titled Mob Daughter: The Mafia, Sammy "The Bull" Gravano, and Me!

Later in his mob career, Gravano was ordered to arrange the murder of his brother-in-law, Nicholas Scibetta.[8] Gravano is also the brother-in-law of Gambino soldier Eddie Garafola.[9] Gravano was a childhood friend of Colombo crime family associate Gerard Pappa, who was also the leader of The Rampers.[9]

Colombo associate

[edit]The Mafia had a longstanding presence in Bensonhurst via the Profaci family, which evolved into the Colombo family. Despite his father's attempts to dissuade him, Gravano, like many of his Ramper colleagues, drifted into the Cosa Nostra. He first became associated with the Cosa Nostra in 1968 through his friend Tommy Spero, whose Uncle Shorty (also named Tommy) Spero was an associate of the Colombo family under future boss, Carmine "The Snake" Persico.[4] Gravano was initially involved in crimes such as larceny, hijacking, and armed robbery.[10] He quickly moved into racketeering, loansharking, and running a lucrative poker game in the back room of an after-hours club, of which he was part owner.[4]

Gravano became a particular favorite of family boss Carmine Persico, who used Gravano to picket the FBI Manhattan headquarters as part of Joe Columbo Italian-American Civil Rights League initiative.[9][5] Gravano's rise was so sudden that it was generally understood that he would be among the first to become made when the Cosa Nostra's membership books were reopened (they had been closed since 1957).[9][5]

In 1970, Gravano committed his first murder—that of Joseph Colucci, a fellow Spero associate with whose wife Tommy Spero was having an affair.[5] Gravano described the experience thus:

As that Beatles song played, I became a killer. Joe Colucci was going to die. I was going to kill him because he was plotting to kill me and Shorty Spero. I felt the rage inside me. ... Everything went in slow motion. I could almost feel the bullet leaving the gun and entering his skull. It was strange and deafening. I didn't hear the first shot. I didn't see any blood. His head didn't seem to move. I then shot him a second time ... I felt like I was a million miles away, like this was all a dream.[9]

The Colucci murder won respect and approval from Persico for Gravano.[5] Later in life, Gravano became a mentor to Colucci's son Jack, who became involved in the construction industry as a Gambino associate.

Made man

[edit]In the early 1970s, Colombo soldier Ralph Spero, brother of Shorty, became envious of Gravano's success, fearing that he would become a made man before his son, Tommy.[4] This rivalry culminated with the death of Ralph Ronga, another Colombo family soldier in Ralph Spero's crew. After Ronga's death, a rumor had spread that Gravano had attempted to pick up Ronga's widow Sybil Davies at a bar, though Gravano maintained that Davies was the one hitting on him. Ralph Spero used this rumor in an attempt to gain support to have Gravano killed, or as an excuse to kill Gravano himself. While Shorty Spero believed Gravano rather than Ralph,[9] he and the Colombo hierarchy decided that to avoid conflict, it was best for Gravano to be transferred to the Gambino crime family.[5]

Now with the Gambinos, Gravano became an associate of capo Salvatore "Toddo" Aurello. Aurello quickly took a liking to Gravano and became his mob mentor.[5] Around this time, Gravano took a construction job (he later claimed to have considered leaving the criminal life).[9] A former associate, however, falsely claimed to the New York District Attorney's Office that Gravano and another associate were responsible for a double murder of the Dunn Brothers from 1969.[5] After Gravano was indicted, he desperately needed money to pay his legal bills. He quit his construction job and went on a self-described "robbing rampage" for a year and a half alongside his Goombata Alexander "Allie Boy" Cuomo.[9] A couple weeks into the trial, Gravano's lawyers moved to dismiss the charges due to the witness being declared legally insane. Gravano later said of this legal problem:

That pinch [arrest] changed my whole life. I never, ever stopped a second from there on in. I was like a madman. Never stopped stealing. Never stopped robbing. I was obsessed.[9]

Gravano's robbery spree impressed Aurello, who proposed him for membership in the Gambino family soon after the membership books were reopened. In 1976, Gravano was formally initiated into the Gambino family as a made man, along with Toddo's son, Charlie Boy Aurello. Sammy and Charlie Boy had been friends since they were kids.[11][12]

Gambino soldier

[edit]In 1978, boss Paul Castellano allegedly ordered the murder of Gambino associate Nicholas Scibetta. A cocaine and alcohol user, Scibetta participated in several public fights and insulted the daughter of George DeCicco. Since Scibetta was Gravano's brother-in-law, Castellano asked Frank DeCicco to first notify Gravano of the impending hit. When advised of Scibetta's fate, Gravano was furious. However, Gravano was eventually calmed by DeCicco and accepted Scibetta's death as the punishment earned by his behavior.[13] Gravano later said, "I chose against Nicky. I took an oath that Cosa Nostra came before everything."[13] Scibetta was dismembered and his body was never found, other than a hand.[7]

Gravano later opened an afterhours club in Bensonhurst, called The Bus Stop. One night, the bar was the scene of a violent altercation, involving a rowdy biker gang intent on ransacking the establishment.[9] A melee ensued, in which Gravano broke his ankle and the bikers were chased off. Gravano then went to Castellano and received permission to "kill them all". Along with Liborio "Louie" Milito, Gravano hunted down the leader, wounding him and killing another member of the gang.[5] Castellano was flabbergasted when he learned the crutch-ridden Gravano personally took part in the hit.[5]

Construction magnate

[edit]Like his predecessor Carlo Gambino, Castellano favored emphasizing more sophisticated schemes involving construction, trucking, and garbage disposal over traditional street-level activities such as loansharking, gambling, and hijackings.[5] Castellano had a particular interest in the construction business.[9] Gravano entered into the plumbing and drywall business with his brother-in-law, Edward Garafola.[5] Gravano's construction and other business interests soon earned him a reputation as a "big earner" within the Gambino organization and made him a multi-millionaire, enabling him to build a large estate for his family in rural Cream Ridge, New Jersey.[9] He invested in trotting horses to race at the Meadowlands Racetrack in East Rutherford, New Jersey. Gravano became the operator of a popular discotheque, The Plaza Suite in the Gravesend section of Brooklyn. He reportedly made $4,000 a week from the Plaza Suite. Gravano owned the building and used the bottom level as his business headquarters.[5]

Simone murder

[edit]Gravano further proved himself to Castellano when he interceded in a civil war that had erupted within the Philadelphia crime family. In March 1980, longtime Philadelphia boss Angelo Bruno, was assassinated by his consigliere, Antonio Caponigro, and his brother-in-law Alfred Salerno, without authorization from The Commission. The Commission summoned Caponigro to New York, where it sentenced him to death for his transgression. After Caponigro was tortured and killed, Philip Testa was installed as the new Philadelphia boss and Nicky Scarfo as consigliere. The Commission subsequently placed contracts on Caponigro's co-conspirators, including John "Johnny Keys" Simone, who also happened to be Bruno's cousin. The Simone contract was given to Gravano.[9]

After befriending Simone through a series of meetings, Gravano, with the assistance of Milito and D'Angelo, abducted Simone from Yardley Golf Club in Yardley, Pennsylvania (part of suburban Trenton, New Jersey), and drove him to a wooded area on Staten Island.

Gravano then granted Simone's requests to die with his shoes off, in fulfillment of a promise he had made to his wife, and at the hands of a made man. After Gravano removed Simone's shoes, Milito shot Simone in the back of the head, killing him. Gravano later expressed admiration for Simone as a so-called "man's man", remarking favorably on the calmness with which he accepted his fate.[9]

Fiala murder

[edit]By the early 1980s, the Plaza Suite was a thriving establishment.[14] Patrons often had to wait an hour to get in and the club featured high-profile live acts such as singer Chubby Checker.[14]

In 1982, Frank Fiala, a wealthy businessman and drug trafficker, paid Gravano $40,000 to rent the Plaza Suite for a birthday party he was throwing for himself. Two days after the party, Gravano accepted a $1,000,000 offer from Fiala to buy the establishment, which was much higher than the property value.[5] The deal was structured to include $50,000 cash as a down payment, $650,000 in gold bullion under the table, and a $300,000 payment at the real estate closing.[9]

Before the transaction was completed, Fiala began acting like he already owned the club. Later, after leaving the Plaza Suite, Gravano called Garafola and set up an ambush outside the club, involving Garafola, Milito, D'Angelo, Nicholas Mormando, Michael DeBatt, Thomas Carbonara and Johnny Holmes in the plan.[9] Later that same night, Gravano confronted Fiala on the street as he exited the Plaza Suite among a group of people, asking, "Hey, Frank, how you doing?"[14] As Fiala turned around, surprised to see Gravano, Milito came up behind him and shot him in the head. Milito stood over the body and fired a shot into each of Fiala's eyes as Fiala's entourage and the crowd of people on the street dispersed, screaming. Gravano walked up to Fiala's body and spat on him.[9]

Gravano was never charged for the crime; he had made a $5,000 payoff to the later discredited and disgraced New York Police Department homicide detective Louis Eppolito to ensure the investigation yielded no leads.[14]

Although Gravano evaded criminal charges, he incurred Castellano's wrath over the unsanctioned killing. Afterwards, Gravano attempted to lie low for nearly three weeks, during which time he called his crew together and made the decision to kill Castellano if necessary.[5] Gravano and Milito were then summoned to a meeting with Castellano at a Manhattan restaurant. Castellano had been given the details of what Fiala had done, but he was still livid that Gravano had not come to him first for permission to kill Fiala. Gravano was spared execution when he convinced Castellano that the reason he had kept him in the dark was to protect the boss in case something went wrong with the hit.[5]

Fiala's murder posed one final problem for Gravano in the form of the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). The high publicity generated by the incident triggered an IRS investigation into Gravano and Fiala's deal for the sale of the Plaza Suite and Gravano was subsequently charged with tax evasion. Gravano was represented by Gerald Shargel and was acquitted at trial.[5]

D'Angelo was later killed by a Colombo family associate celebrating his having been proposed for membership. The killer was then murdered on orders from the Colombo family.[5]

Aligning with Gotti

[edit]In the aftermath of the Fiala murder, Gravano continued to focus on his construction business by branching out into the lucrative drywall industry. New York City's cement industry was controlled by four of the Five Families, which made millions of dollars by manipulating bids and steering contracts.[5] Gravano said in 1998, "I literally controlled Manhattan, literally. You want concrete poured in Manhattan? That was me. Tishman, Donald Trump, all these guys—they couldn't build a building without me."[15]

Gravano eventually became embroiled in a dispute with business partner Louie DiBono, a member of another Gambino crew. Gravano, and his brother-in-law Eddie, had a meeting with DiBono, (along with an attorney and an accountant DiBono brought) at which DiBono said only $50,000 was due. Gravano excused the attorney and accountant and, once alone with DiBono, banged him around the room because of the scam.

Putting hands on another made man is a death penalty in Cosa Nostra. DiBono told his captain, Patsy Conti, Conti then told Castellano and a sit-down was called. Toddo spoke on Gravano; Gambino underboss Neil Dellacroce intervened on Gravano's behalf. Castellano told DiBono to pay Gravano $200,000 and the two men end their business partnership.[9] Gravano's standing with his boss slipped as a result of the incident. Dellacroce, however, was the mentor to rising star John Gotti, and when word got back to him that Dellacroce had supported Gravano, Gotti and other Gambino members were impressed.[5]

During this time, the FBI had intensified its efforts against the Gambino family and in August 1983, three members of Gotti's crew – Angelo Ruggiero, John Carneglia, and Gene Gotti – were indicted for heroin trafficking. Castellano was against anyone in the family dealing narcotics. Castellano planned to kill Gene Gotti and Ruggiero if he believed they were drug traffickers. Castellano asked Ruggiero for a copy of the government surveillance tapes that had Ruggiero's conversations. To save Gene Gotti and Ruggiero, Dellacroce stalled the demand. Eventually, one of the reasons for Gotti's killing Castellano was to save himself, his brother and Ruggiero. The Ruggiero tapes not only had them talking about drugs, but also the bosses and commission. The FBI had bugged Ruggiero's house and telephone, and Castellano decided he needed copies of the tapes to justify his impending move to Dellacroce and the family's other capos.[5][16]

When Castellano was indicted for both his connection to Roy DeMeo's stolen car ring and as part of the Mafia Commission Trial, he learned his own house had been bugged on the basis of evidence from the Ruggiero tapes and he became livid.[5] In June 1985, he again demanded that Dellacroce get him the tapes. Dellacroce tried to convince Gotti and Ruggiero to comply if Castellano explained beforehand how he intended to use the tapes, but Ruggiero refused, fearing he would endanger good friends.[16]

Prior to Castellano's indictment, Gravano was approached by Robert DiBernardo, a fellow Gambino member acting as an intermediary for Gotti. DiBernardo informed him that Gotti and Ruggiero wanted to meet with him in Queens. Gravano arrived to find only Ruggiero was present. Ruggiero informed Gravano that he and Gotti were planning to murder Castellano and asked for Gravano's support.[5]

Gravano was initially noncommittal, wanting to confer first with Frank DeCicco. In conversation with DeCicco, both men voiced concern that Castellano would designate his nephew, Thomas Gambino, acting boss and his driver, Thomas Bilotti, underboss in the event he was convicted and sent to prison. Neither man appeared to Gravano or DeCicco as leadership material, and they ultimately decided to support the hit on Castellano.[9]

Castellano murder

[edit]Gravano's first choice to become boss after Castellano's murder was Frank DeCicco, but DeCicco felt John Gotti's ego was too big to take a subservient role.[9] DeCicco argued that Gotti's boldness, intelligence, and charisma made him well-suited to be "a good boss" and he convinced Gravano to give Gotti a chance. DeCicco and Gravano made a secret pact to kill Gotti and take over the family as boss and underboss, respectively, if they were unhappy with Gotti's leadership after one year.[9] The conspirators' first order of business was meeting with other Gambino members, most of whom were dissatisfied under Castellano, to gain their support for the hit.[4] They also recruited longtime capo Joseph "Piney" Armone into the conspiracy. Armone's support was critical; he was a respected old-timer in the family, and it was believed he could help win over Castellano supporters to the new regime.[17]

The next step was smoothing over the planned hit with the other families. It has long been a hard and fast rule in the Mafia that killing a boss is forbidden without the support of a majority of the Commission. Indeed, Gotti's planned hit would have been the first off-the-record hit on a boss since Frank Costello was nearly killed in 1957. Knowing it would be too risky to approach the other four bosses directly, the conspirators got the support of several important mobsters of their generation in the Lucchese, Colombo and Bonanno families.[17]

Gotti and Ruggiero then sought and obtained the approval of key figures from the Colombos and Bonannos, while DeCicco secured the backing of top mobsters aligned with the Luccheses.[9] They did not even consider approaching the Genoveses; Castellano had especially close ties with Genovese boss Vincent "Chin" Gigante, and approaching any major Genovese figure, even one of their generation, could have been a tipoff. Gotti could thus claim he had the support of "off-the-record contacts" from three out of five families.[17] With Neil Dellacroce's death on December 2, 1985, the final constraint on a move by Gotti or Castellano against the other was removed. Gotti, enraged that Castellano chose not to attend his mentor's wake, wasted little time in striking.[5]

Not suspecting the plot against him, Castellano invited DeCicco to a meeting on December 16, 1985, with fellow capos Thomas Gambino, James Failla, Johnny Gamorana, and Danny Marino at Sparks Steak House in Manhattan. The conspirators considered the restaurant a prime location for the hit because the area would be packed with bustling crowds of holiday shoppers, making it easier for the assassins to blend in and escape.[4] The plans for the assassination were finalized on December 15, and the next afternoon, the conspirators met for a final time on the Lower East Side. At Gotti's suggestion, the shooters wore long white trench coats and black fur Russian hats, which Gravano considered a "brilliant" idea.[9]

Gotti and Gravano arrived at the restaurant shortly before 5 o'clock and, after circling the block, parked their car across the intersection and within view of the entrance.[9] Around 5:30, Gravano spotted Castellano's Lincoln Town Car at a nearby intersection and, via walkie talkie, alerted the team of hitmen stationed outside the restaurant of Castellano's approach.[18] Castellano's driver, Thomas Bilotti, pulled the car up directly in front of the entrance. As Castellano and Bilotti exited the Lincoln, they were ambushed and killed in a barrage of bullets.[18] As the hat-and-trench-coat-adorned men slipped away into the night, Gotti calmly drove the car past the front of the restaurant to get a look at the scene.[5] Looking down at Bilotti's body from the passenger window, Gravano remarked, "He's gone."[18]

The new regime

[edit]After Castellano's death, Gallo–the only surviving member of the hierarchy–convened a three-man committee to temporarily run the family, comprising himself, Gotti and DeCicco. However, it was an open secret that Gotti was acting boss in all but name, and nearly all of the family's capos knew he had been the one behind the hit. Gotti was formally acclaimed as the new boss of the Gambino family at a meeting of 20 capos held on January 15, 1986.[19] Gotti, in turn, selected DeCicco as his underboss and elevated Gravano to capo after Toddo Aurello announced his desire to step down.[5]

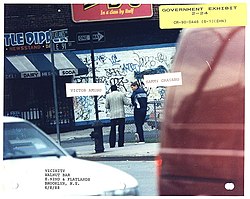

On April 13, 1986, DeCicco was killed when his car was bombed following a visit to Castellano loyalist James Failla. The bombing was carried out by Victor Amuso and Anthony Casso of the Lucchese family, under orders of Vincent Gigante and Lucchese boss Anthony Corallo, to avenge Castellano and Bilotti by killing their successors; Gotti also planned to visit Failla that day, but canceled. The bomb was detonated after a soldier, Frankie Hearts, asked DeCicco for a lawyers business card. DeCicco went to his car to retrieve the card and when he sat in the passenger seat, the bomb exploded.[20][21][22]

Bombs had long been banned by the Mafia out of concern that it would put innocent people in harm's way, leading the Gambinos to initially suspect that "zips" — Sicilian mafiosi working in the U.S. — were behind it; zips were well known for using bombs.[23]

"Nicky Cowboy" murder

[edit]The first person on Gravano's hit list after Castellano's murder was Nicholas "Nicky Cowboy" Mormando, a former member of his crew. Mormando had become addicted to crack cocaine and was suspected by Gravano of getting friend and fellow crew member Michael DeBatt addicted to the drug. Gravano decided because of Nicky's reckless behavior, including getting DeBatt addicted to crack, he would get permission from Gotti to kill Mormando.[9]

Gravano arranged to have Mormando murdered on his way to a meeting at Gravano's Bensonhurst restaurant, Tali's. After assuring Mormando of his safety, Gravano told him to pick up Joseph Paruta on his way. Paruta got in the backseat of the car and shot Mormando twice in the back of the head. Mormando's corpse was then disposed of in a vacant lot, where it was discovered the next day.[9]

Consigliere and underboss

[edit]

Gotti was imprisoned in May 1986 at the Metropolitan Correctional Center, New York, while awaiting trial on Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) charges. He relied heavily on Gravano, Angelo Ruggiero, and Joseph "Piney" Armone to manage the family's day-to-day affairs while he called the major shots from his jail cell.[citation needed]

In June, Gravano was approached by Ruggiero and, supposedly at Gotti's behest, given orders to murder capo Robert DiBernardo for making negative remarks about Gotti's leadership. Gravano was friendly with DiBernardo and tried to get the murder called off until he had a chance to speak with Gotti after his trial. Gravano met with Joseph Piney where Piney explained Gotti wanted DiBernardo dead. Ruggiero claimed to have met again with Gotti and told Gravano that the boss wanted DiBernardo killed right away.[9]

Gravano arranged a meeting with DiBernardo where Joe Paruta, a member of Gravano's crew, shot DiBernardo twice in the back of the head as Gravano watched. Gravano later learned that Ruggiero was $250,000 in debt to DiBernardo and realized Ruggiero may have fabricated the orders from Gotti or simply lied to Gotti about what DiBernardo was accused of saying in order to erase the debt and improve his own standing in the family.[9] In any event, DiBernardo's death proved profitable for Gravano, as he took over the deceased man's control of Teamsters Local 282.[5]

Gotti's trial ultimately ended in a mistrial due to a hung jury and the boss was freed from jail. Gravano's specific position within the family varied during 1986 and 1987. With Gotti's permission, Gravano set up several murders with other Gambino associates. In 1986, Gotti underwent a racketeering trial. Jury selection for the racketeering case began again in August 1986,[24] with Gotti standing trial alongside Gene "Willie Boy" Johnson (who, despite being exposed as an informant, refused to turn state's evidence[25]), Leonard DiMaria, Tony Rampino, Nicholas Corozzo and John Carneglia.[26]

At this point, the Gambinos were able to compromise the case when George Pape hid his friendship with Boško Radonjić and was empaneled as juror No. 11.[27] Through Radonjić, Pape contacted Gravano and agreed to sell his vote on the jury for $60,000.[28] On March 13, 1987, they acquitted Gotti and his codefendants of all charges.[26] In the face of previous Mafia convictions, particularly the success of the Mafia Commission Trial, Gotti's acquittal was a major upset that further added to his reputation. The American media dubbed Gotti "The Teflon Don" in reference to the failure of any charges to "stick".[29]

With DeCicco dead, the Gambinos were left without an underboss. Gotti chose to fill the vacancy with Joseph Armone.[30][31]

In 1987, Joseph N. Gallo was replaced with Gravano as consigliere, and by 1990, Gravano was promoted to underboss to replace the acting underboss Frank LoCascio.[9][30][32][33] By this time, Gravano was regarded as a "rising force" in the construction industry and often mingled with executives from major construction firms and union officials at his popular Bensonhurst restaurant, Tali's.[9]

Gravano's success was not without a downside. First, his quick rise up the Gambino hierarchy attracted the attention of the FBI, and he was soon placed under surveillance. Second, he started to sense some jealousy from Gotti over the profitability of his legitimate business interests. Nevertheless, Gravano claimed to be kicking up over $2 million each year to Gotti out of his union activities alone.[5] Beginning in January 1988, Gotti, against Gravano's advice,[34] required his capos to meet with him at the Ravenite Social Club once a week.[35]

Turning government witness

[edit]Gotti, Gravano and LoCascio were often recorded by the bugs placed throughout the Ravenite (concealed in the main room, the first-floor hallway and the upstairs apartment of the building) discussing incriminating events.[36] On December 11, 1990, FBI agents and NYPD detectives raided the Ravenite, arresting Gravano, Gotti and LoCascio. Gravano pleaded guilty to a superseding racketeering charge, and Gotti was charged with five murders (Castellano, Bilotti, DiBernardo, Liborio Milito and Louis Dibono), conspiracy to murder Gaetano Vastola, loansharking, illegal gambling, obstruction of justice, bribery and tax evasion.[37][38]

Based on tapes from FBI bugs played at pretrial hearings, the Gambino administration was denied bail. At the same time, attorneys Bruce Cutler and Gerald Shargel were disqualified from defending Gotti and Gravano after prosecutors successfully contended they were "part of the evidence" and thus liable to be called as witnesses. Prosecutors argued that Cutler and Shargel not only knew about potential criminal activity, but had worked as "in-house counsel" for the Gambino family.[39][40] Gotti subsequently hired Albert Krieger, a Miami attorney who had worked with Joseph Bonanno, to replace Cutler.[41][42]

The tapes also created a rift between Gotti and Gravano, as they contained recordings of the Gambino boss describing his newly appointed underboss as too greedy and included discussions of Gotti's intent to frame Gravano as the main force behind the murders of DiBernardo, Milito and Dibono.[43][44]

Gotti's attempt at reconciliation with Gravano failed,[45] leaving Gravano disillusioned with the mob and doubtful on his chances of winning his case without Shargel, his former attorney.[46][47] Gravano ultimately opted to turn state's evidence, formally agreeing to testify on November 13, 1991.[48][49] He was the first member of the hierarchy of a New York crime family to turn informer, and the second confessed underboss in the history of the American Mafia to do so after the Philadelphia crime family's Phil Leonetti.[citation needed]

Gotti and LoCascio were tried in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York before District Judge I. Leo Glasser. Jury selection began in January 1992 with an anonymous jury and, for the first time in a Brooklyn federal case, fully sequestered during the trial due to Gotti's reputation for jury tampering.[50][51] The trial commenced with the prosecution's opening statements on February 12;[52][53] prosecutors Andrew Maloney and John Gleeson began their case by playing tapes showing Gotti discussing Gambino family business, including murders he approved, and confirming the animosity between Gotti and Castellano to establish the former's motive to kill his boss.[54]

After calling an eyewitness of the Sparks hit who identified Carneglia as one of the men who shot Bilotti, they then brought Gravano to testify on March 2.[55][56][57] On the stand, Gravano confirmed Gotti's place in the structure of the Gambino family and described in detail the conspiracy to assassinate Castellano, giving a full description of the hit and its aftermath.[58] Gravano confessed to 19 murders, implicating Gotti in four of them.[59] Krieger, and LoCascio's attorney, Anthony Cardinale, proved unable to shake Gravano during cross-examination.[60][61] After additional testimony and tapes, the government rested its case on March 24.[62] Among other outbursts, Gotti called Gravano a junkie while his attorneys sought to discuss his past steroid use.[63][64]

On June 23, 1992, Glasser sentenced Gotti and LoCascio to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole and a $250,000 fine. Gotti surrendered to federal authorities to serve his prison time on December 14, 1992.[38][65][66] On September 26, 1994, a federal judge sentenced Gravano to five years in prison. However, since Gravano had already served four years, the sentence amounted to less than one year.[67] In total, Gravano implicated 29 mobsters to the law; Gambino mobsters, former boss John Gotti, former Gambino family consigliere Frank LoCascio,[68] current and former captains Robert Bisaccia,[69] Thomas Gambino, Pasquale Conte,[70] Joseph Corrao, James Failla, Daniel Marino,[71] John Gambino, Ralph Mosca; current and former soldier's, Paul Graziano, Anthony Vinciullo, Domenico Cefalu (current Gambino family boss), Francesco Versaglio, Orazio Stantini, Louis Astuto, Dominic Borghese,[72] Joseph Gambino, Peter Mosca, Virgil Alessi;[73] current and former associates, Lorenzo Mannino (current Gambino family acting boss), Joseph Passanante, George Helbig,[74] Peter Mavis,[75] Barry Nichilo. Apart from the Gambino family, Gravano also testified against Colombo crime family acting boss Vic Orena and consigliere Benedetto Aloi, Genovese crime family underboss Venero Mangano and the New Jersey DeCavalcante crime family boss Giovanni Riggi.

Later life

[edit]Book and interviews

[edit]Later in 1994, Gravano was released early and entered the U.S. federal Witness Protection Program. The government moved him to various locations until Gravano left the program in 1995 after only 8 months and moved to Phoenix, AZ, where he assumed the name Jimmy Moran and started a swimming pool installation company.[76]

A federal prosecutor later said that Gravano did not like the constraints of the program.[77] Gravano began living openly, giving interviews to magazines, and appearing in a nationally televised interview with television journalist Diane Sawyer. It was reported that he had undergone plastic surgery to his face.[78] In 1991, his wife Debra divorced him.[79]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

In 1997, Gravano was consulted several times for the 1997 biographical book about his life, Underboss, by author Peter Maas. In it, Gravano said he became a government witness after Gotti attempted to defame him at their trial. Gravano finally realized that the Cosa Nostra code of honor was a sham. At that time, Gravano also hired a publicist, despite the fact Gravano complained often about the publicity-seeking Gotti. After the publication of Underboss, several families of Gravano's victims filed a $25 million lawsuit against him, however the families lost that case. In 1997, New York State indicted Gravano on an old RICO case and seized Gravano's profits from the book.[80]

During an interview Gravano had with the newspaper The Arizona Republic, he said federal agents he had met after becoming a government witness had become his personal friends and even visited him in Arizona while on vacation. Gravano later said that he did not want The Republic to publish the story, but relented after the paper allegedly threatened to reveal that his family was living with him in Phoenix. The story so incensed his former mob compatriots that they forced the Gambinos to put a murder contract on him.[81] The FBI alleged that Peter Gotti ordered two Gambino soldiers, Thomas "Huck" Carbonaro and Eddie Garafola, to murder Gravano in Arizona in 1999.[82]

Drug conviction

[edit]By the late 1990s, Gravano had re-engaged in criminal activity. His son, Gerard, became friends with 23-year-old Michael Papa, a Devil Dogs gang leader. Gravano started a major ecstasy trafficking organization, selling over 30,000 tablets and reportedly grossing $500,000 a week.[83]

In February 2000, Gravano and nearly 40 other ring members — including his ex-wife Debra, daughter Karen, and Gerard — were arrested on federal and state drug charges. Gravano was implicated by informants in his own drug ring, as well as by recorded conversations in which he discussed drug profits with Debra and Karen.[11]

On May 25, 2001, Gravano pleaded guilty in a New York federal court to drug trafficking charges.[11] On June 29, 2001, Gravano pleaded guilty in Phoenix to the state charges.[76]

In 2002, Gravano was diagnosed with Graves' disease, a thyroid disorder that can cause fatigue, weight loss with increased appetite, and hair loss.[84]

On September 7, 2002, after numerous delays, Gravano was sentenced in New York to 20 years in prison.[77] A month later, he was also sentenced in Arizona to 19 years in prison, to run concurrently, but was also granted lifetime supervised release and a $100,000 fine.[85] Gravano served his sentence at ADX Florence, part of it being in solitary confinement.[86] Gerard Gravano received nine years in prison in October 2002.[87] Debra and Karen Gravano also pleaded guilty and received several years on probation. In November 2003, Sammy and Karen were ordered to pay $805,713 as reimbursement for court costs and investigative expenses relating to an earlier drug ring judgment.[85]

On February 24, 2003, New Jersey state prosecutors announced Gravano's indictment for ordering the 1980 killing of NYPD detective Peter Calabro by murderer Richard Kuklinski.[88] Gravano denied any involvement in Calabro's death and rejected a plea deal, under which he would have received no additional jail time if he confessed to the crime and implicated all his accomplices.[89][90] The charges against Gravano were dropped after Kuklinski's death in 2006.[91]

In August 2015, Gravano's request to leave prison early was denied due to his "long-standing reputation for extreme violence".[92]

Gravano was listed as being in the Arizona state prison system, at a CO Special Services unit. He was initially scheduled for release in March 2019; however, he was released on September 18, 2017.[93][94][95]

Media appearances

[edit]In 2013, National Geographic Channel dramatized Gravano's ecstasy ring in a scene in the Banged Up Abroad episode "Raving Arizona", televised worldwide. The episode told the story of ecstasy dealer "English" Shaun Attwood, who was Gravano's main competitor in the Arizona ecstasy market.[96][97]

In December 2020, Gravano started a YouTube channel and a podcast titled Our Thing.[98]

See also

[edit]- Witness to the Mob, a made-for-TV film based on the rise of Sammy Gravano through the ranks of the Gambino crime family.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "About Salvatore Sammy The Bull Gravano". YouTube.

- ^ Cassidy, John (April 13, 2018). "James Comey and Donald Trump Go to War". The New Yorker. New York City. Archived from the original on April 16, 2018. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ a b c Peter Maas (1997). Underboss. New York City: HarperCollins. p. 3. ISBN 0-06-018256-3.

- ^ a b c d e f Robinson, Paul H.; Michael T. Cahill (2005). Law Without Justice: Why Criminal Law Doesn't Give People What They Deserve. Oxford University Press. pp. 74–80. ISBN 0-19-516015-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af May, Allan. "Sammy "The Bull" Gravano". TruTV.com. Archived from the original on December 17, 2008. Retrieved February 11, 2012.

- ^ Maas, page 9

- ^ a b "Gravano killed brother-in-law, defense attorney says N.Y. judge rules revelations were too inflammatory for Gotti mob jury to hear". baltimoresun.com. March 12, 1992. Archived from the original on 2019-08-12. Retrieved 2019-09-14.

- ^ Raab, Selwyn (September 26, 1994). "Signing for Your Sentence: How Will It Pay Off?; Ex-Crime Underboss May Find Out Today What He Gets for Turning U.S. Witness". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 25, 2009. Retrieved June 12, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Peter Maas (1997). Underboss. New York City: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-018256-3.

- ^ Lubasch, Arnold H. (March 3, 1992). "Gotti Confidant Tells Courtroom Of Mafia Family's Violent Reign". The New York Times. New York City. Archived from the original on August 22, 2019. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ^ a b c Feuer, Alan (May 26, 2001). "Gravano and Son Plead Guilty To Running Ecstasy Drug Ring". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 24, 2014. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ^ "Five Mafia Families Open Rosters to New Members". The New York Times. March 21, 1976. Archived from the original on April 6, 2020. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- ^ a b May, Allan. "Living by the Rules". Sammy "The Bull" Gravano. Crime Library. Archived from the original on 24 April 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ^ a b c d Lawson, Guy; William Oldham (August 28, 2007). The Brotherhoods: The True Story of Two Cops Who Murdered for the Mafia. Pocket. p. 768. ISBN 978-1-4165-2338-3.

- ^ Goldberg, Jeffrey (August 23, 2018). "Donald Trump's Mafia Mind-Set". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on January 8, 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^ a b Bowles, Peter (February 26, 1992). "Tapes Called Gotti Murder Motive". Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on August 24, 2009. Retrieved July 9, 2009.

- ^ a b c Raab, pg. 375.

- ^ a b c Miller, John. "Gotti, A Mob Icon". ABC News. Archived from the original on August 22, 2009. Retrieved July 9, 2009.

- ^ Raab, pp. 377-378.

- ^ Raab, pp. 473–476

- ^ Capeci, Jerry (January 2005). The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Mafia. Alpha. p. 464. ISBN 1-59257-305-3.

- ^ Capeci, Jerry; Gene Mustain (June 1, 1996). Gotti: Rise and Fall. Onyx. pp. 448. ISBN 0-451-40681-8.

- ^ Capeci, Mustain (1996), pp. 139–140

- ^ Capeci, Mustain (1996), pg. 159

- ^ Raab, pg. 392

- ^ a b Buder, Leonard (March 14, 1987). "Gotti Is Acquitted In Conspiracy Case Involving The Mob". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 1, 2013. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

John Gotti was acquitted of federal racketeering and conspiracy charges yesterday

- ^ Lubasch, Arnold (November 7, 1992). "Juror Is Convicted of Selling Vote to Gotti". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 1, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ Capeci, Mustain (1996), pp. 173–175

- ^ Raab, pp. 397-399

- ^ a b Capeci, Jerry (1996). Gotti: The Rise and Fall. Gene Mustain. New York, N.Y.: Penguin Group. ISBN 9781448146833. OCLC 607612904.

- ^ Maas, pg. 382

- ^ "How Gotti's No. 2 Gangster Turned His Coat". The New York Times. November 15, 1991.

- ^ Capeci, Mustain (1996), pp. 195–196

- ^ Capeci, Mustain (1996), pg. 230

- ^ Capeci, Mustain (1996), pg. 225

- ^ "Words From Gotti's Mouth: Secret Tapes of Inner Circle". The New York Times. August 3, 1991.

- ^ Davis, pp. 370–371

- ^ a b "United States of America, Appellee, v. Frank Locascio, and John Gotti, Defendants-Appellants". ispn.org. United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. October 8, 1993. Archived from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved March 9, 2012.

- ^ Davis, pp. 372, 375–376

- ^ Capeci, Mustain (1996), pp. 391, 397

- ^ Davis, pg. 384

- ^ Capeci, Mustain (1996), pp. 400–401

- ^ Davis, pp. 426–427

- ^ Capeci, Mustain (1996), pp. 384–388

- ^ Capeci, Mustain (1996), pp. 389–390

- ^ Davis, pg. 399

- ^ Capeci, Mustain (1996), pg. 393

- ^ Capeci, Mustain (1996), pg. 413

- ^ Raab, Selwyn (November 12, 1991). "U.S. Says Top Gotti Aide Will Testify Against Boss". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 23, 2011. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ^ Capeci, Mustain (1996), pg. 417

- ^ Arnold H. Lubasch (April 1, 1992). "Deliberations Set to Start in Gotti's Rackets Trial". The New York Times. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ Capeci, Mustain (1996), pg. 422

- ^ Arnold H. Lubasch (February 13, 1992). "Prosecution in Gotti Trial To Stress Secret Tapes". The New York Times. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ Davis, pp. 412–421

- ^ Davis, pp. 421–422, 428

- ^ Capeci, Mustain (1996), pp. 425–426

- ^ Arnold H. Lubasch (February 27, 1992). "Witness Describes Scene at Murder of Castellano". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 4, 2010. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ Davis, pp. 428–444

- ^ "Gotti Associate Testifies To Role in 19 Slayings". Los Angeles Times. March 5, 1992. Archived from the original on December 30, 2019. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ Davis, pp. 444–454

- ^ Capeci, Mustain (1996), pp. 427–431

- ^ Capeci, Mustain (1996), pp. 432–433.

- ^ Davis, pg. 453

- ^ Capeci, Mustain (1996), pg. 431

- ^ Capeci, Mustain (1996), pp. 435–437

- ^ Davis, pp. 486–487

- ^ "Ex-Mob Underboss Given Lenient Term For Help as Witness". The New York Times. September 27, 1994. Archived from the original on January 5, 2019.

- ^ Lubasch, Arnold. "Gotti Confidant Tells Courtroom Of Mafia Family's Violent Reign". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ Jackson, Chanta (4 December 2008). "Iconic 'Goodfella' Robert Bisaccia dies in prison". NJ.com. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ Fried, Joseph. "3 Reputed Gotti Associates Charged With Murder". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ "Federal prosecutors are charging three men with eavesdropping on". UPI. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ Feuer, Alan. "https://www.nytimes.com/2001/06/10/nyregion/reporter-s-notebook-what-mobsters-chat-about-glory-days-and-bad-teeth.html". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ "4 Indicted in Plot To Kill Informer". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ Raab, Selwyn. "Jury Indicts A Detective In Gotti Leaks". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ "United States v. Gotti". Case Text. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ a b Feuer, Alan (June 30, 2001). "Gravano Pleads Guilty To Drug Sales In Arizona". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 29, 2012. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ^ a b Newman, Andy (September 7, 2002). "Mafia Turncoat Gets 20 Years for Running Ecstasy Ring". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ^ "Informants No Longer Bother to Run From the Mob". Los Angeles Times. January 2, 2000. Archived from the original on January 28, 2020. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ "Did Gravano return to old life?". Times Daily. March 19, 2000. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ Raab, Selwyn (April 17, 1997). "New York Stakes Claim On Mobster's Book Money". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ^ Raab, Selwyn. The Five Families: The Rise, Decline & Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empire. New York: St. Martins Press, 2005.

- ^ "Plot To Kill Sammy No Bull: Feds Say Peter Gotti Ordered Hit". The New York Daily News. 19 August 2003. Archived from the original on June 17, 2018. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- ^ "Mob canary 'Sammy The Bull' flies coop". The Toronto Sun. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ^ Raab, Selwyn (2013). Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empires. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 451. ISBN 978-1-4299-0798-9. OCLC 865093057.

- ^ a b "Sammy the Bull Gravano Ordered to Pay $805,713.41 for Arizona Drug Related Crimes". azag.gov. November 18, 2003. Archived from the original on December 30, 2019. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ "Sammy 'The Bull' Did Not get out early". 12news.com. September 22, 2017. Archived from the original on September 18, 2020. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ "Mob informant's son gets nine years for part in Ecstasy ring". azdailysun.com. October 17, 2002. Archived from the original on December 30, 2019. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ Jacobs, Andrew (February 25, 2003). "Hit Man Implicates Hit Man In '80 Slaying, Authorities Say". New York Times. Archived from the original on December 26, 2017.

- ^ "'Bull' Rejected Plea in Cop Killing". The Record. March 8, 2006.

- ^ "Gravano: "Bull" Rejected 2003 Plea Deal in Case of Slain Cop". The Record. March 8, 2006.

- ^ Hague, Jim (March 20, 2006). ""The 'Iceman' cometh - and goeth Gruesome hit man and former NB resident Kuklinski, featured in HBO special, dies in prison at 70"". Hudson Reporter. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021.

- ^ "Mob 'Bull' fails in bid to have jail sentenced shortened". nypost.com. August 28, 2015. Archived from the original on May 18, 2020. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ "Mob boss 'Sammy the Bull' Gravano released from prison early". September 20, 2017. Archived from the original on February 9, 2018. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- ^ "Former mob figure "Sammy the Bull" released from prison". Crimesider Staff. Phoenix: CBS Interactive Inc. CBS News. September 21, 2017. Archived from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ "Former Mobster Sammy 'The Bull' Gravano Released From Prison". usnews.com. US News. September 22, 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-11-07. Retrieved 2017-11-04.

- ^ "Locked Up Abroad: Where Are They Now?: Shaun Attwood". April 25, 2013. Archived from the original on July 8, 2017. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ Buchanan, Susy; Kelley, Brendan Joel (July 18, 2002). "Evil Empire". Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ McShane, Larry (12 December 2020). "No Bull! Ex-Gambino family underboss Sammy Gravano's new podcast debuting this week". NY Daily News. Archived from the original on 2021-01-03. Retrieved 2021-01-27.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Sammy Gravano at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sammy Gravano at Wikimedia Commons

- Sammy Gravano official website

- Sammy "The Bull" Gravano Biography at Crimelibrary.com

- Salvatore Gravano Arizona Inmate Information

- Maas, Peter. Underboss. 1997. ISBN 0-06-018256-3

- Documentary series from Court TV (now TruTV) "MUGSHOTS: Sammy "The Bull" Gravano" Archived 2017-08-12 at the Wayback Machine episode (2003) at FilmRise

- Booknotes interview with Maas about Underboss: Sammy The Bull Gravano's Story of Life in the Mafia, August 24, 1997

- 1945 births

- American gangsters of Italian descent

- People of Sicilian descent

- FBI informants convicted of crimes

- Gambino crime family

- Inmates of ADX Florence

- Living people

- Mafia hitmen

- People convicted of racketeering

- People from Bensonhurst, Brooklyn

- People who entered the United States Federal Witness Protection Program

- American Mafia cooperating witnesses

- United States Army non-commissioned officers

- Military personnel from New York City

- American people convicted of drug offenses

- People with dyslexia

- American people with disabilities

- YouTube channels launched in 2020

- YouTubers from Brooklyn