Gametogenesis

| Part of a series on |

| Sex |

|---|

|

| Biological terms |

| Sexual reproduction |

| Sexuality |

| Sexual system |

Gametogenesis is a biological process by which diploid or haploid precursor cells undergo cell division and differentiation to form mature haploid gametes. Depending on the biological life cycle of the organism, gametogenesis occurs by meiotic division of diploid gametocytes into various gametes, or by mitosis. For example, plants produce gametes through mitosis in gametophytes. The gametophytes grow from haploid spores after sporic meiosis. The existence of a multicellular, haploid phase in the life cycle between meiosis and gametogenesis is also referred to as alternation of generations.

It is the biological process of gametogenesis during which cells that are haploid or diploid divide to create other cells. It can take place either through mitotic or meiotic division of diploid gametocytes into different cells depending on an organism's biological life cycle. For instance, gametophytes in plants undergo mitosis to produce gametes. Both male and female have different forms.[1]

In animals

[edit]

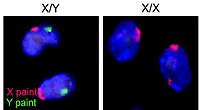

Animals produce gametes directly through meiosis from diploid mother cells in organs called gonads (testis in males and ovaries in females). In mammalian germ cell development, sexually dimorphic gametes differentiates into primordial germ cells from pluripotent cells during initial mammalian development.[2] Males and females of a species that reproduce sexually have different forms of gametogenesis:

- spermatogenesis (male): Immature germ cells are produced in a man's testes. To mature into sperms, males' immature germ cells, or spermatogonia, go through spermatogenesis during adolescence. Spermatogonia are diploid cells that become larger as they divide through mitosis. These are primary spermatocytes. These diploid cells undergo meiotic division to create secondary spermatocytes. These secondary spermatocytes undergo a second meiotic division to produce immature sperms or spermatids. These spermatids undergo spermiogenesis in order to develop into sperm. LH, FSH, GnRH, and androgens are just a few of the hormones that help to promote spermatogenesis.

- oogenesis (female)

Stages

[edit]However, before turning into gametogonia, the embryonic development of gametes is the same in males and females.

Common path

[edit]Gametogonia are usually seen as the initial stage of gametogenesis. However, gametogonia are themselves successors of primordial germ cells (PGCs) from the dorsal endoderm of the yolk sac migrate along the hindgut to the genital ridge. They multiply by mitosis, and, once they have reached the genital ridge in the late embryonic stage, are referred to as gametogonia. Once the germ cells have developed into gametogonia, they are no longer the same between males and females.

Individual path

[edit]From gametogonia, male and female gametes develop differently - males by spermatogenesis and females by oogenesis. However, by convention, the following pattern is common for both:

| Cell type | ploidy/chromosomes in humans | DNA copy number/chromatids in human[Note 1] | Process |

|---|---|---|---|

| gametogonium | diploid (2N)/46 | 2C before replication, 4C after 46 before, 46 × 2 after |

gametocytogenesis (mitosis) |

| primary gametocyte | diploid (2N)/46 | 2C before replication, 4C after 46 before, 46 × 2 after |

gametidogenesis (meiosis I) |

| secondary gametocyte | haploid (N)/23 | 2C / 46 | gametidogenesis (meiosis II) |

| gametid | haploid (N)/23 | C / 23 | |

| gamete | haploid (N)/23 | C / 23 |

In vitro gametogenesis

[edit]In vitro gametogenesis (IVG) is the technique of developing in vitro generated gametes, i.e., "the generation of eggs and sperm from pluripotent stem cells in a culture dish."[3] This technique is currently feasible in mice and will likely have future success in humans and nonhuman primates.[3] It allows scientists to create sperms and egg cells by reprograming adult cells. This way, they could grow embryos in a laboratory. Even though it is a promising technique for fighting disease, it raises several ethical problems.[4]

In gametangia

[edit]Fungi, algae, and primitive plants form specialized haploid structures called gametangia, where gametes are produced through mitosis. In some fungi, such as the Zygomycota, the gametangia are single cells, situated on the ends of hyphae, which act as gametes by fusing into a zygote. More typically, gametangia are multicellular structures that differentiate into male and female organs:

- antheridium (male)

- archegonium (female)

In angiosperms

[edit]In angiosperms, the male gametes (always two) are produced inside the pollen tube (in 70% of the species) or inside the pollen grain (in 30% of the species) through the division of a generative cell into two sperm nuclei. Depending on the species, this can occur while the pollen forms in the anther (pollen tricellular) or after pollination and growth of the pollen tube (pollen bicellular in the anther and in the stigma). The female gamete is produced inside the embryo sac of the ovule.

In angiosperms the division of a generative cell into two, sperm nuclei, resulting in the production male gametes (always two), which develop inside the pollen grain (in 30% of species) or the pollen tube (in 70% of species), respectively,) of the plant. This may happen before pollination and the development of the pollen tube, depending on the species, or while the pollen is still forming in the anther (pollen is tricellular) (pollen bicellular in the anther and in the stigma). Inside the embryo sac of the ovule, the female gamete is created.

Meiosis

[edit]Meiosis is a central feature of gametogenesis, but the adaptive function of meiosis is currently a matter of debate. A key event during meiosis is the pairing of homologous chromosomes and recombination (exchange of genetic information) between homologous chromosomes. This process promotes the production of increased genetic diversity among progeny and the recombinational repair of damage in the DNA to be passed on to progeny. To explain the adaptive function of meiosis (as well as of gametogenesis and the sexual cycle), some authors emphasize diversity,[5] and others emphasize DNA repair.[6]

Although meiosis is a crucial component of gametogenesis, its function in adaptation is still unknown. In sexually reproducing organisms, it is a type of cell division that results in fewer chromosomes being present in gametes.[7]

HOMOLOGY EFFECTS

There are two key differences between mammalian and plant gametogenesis. First, there is no predetermined germline in plants. Male or female gametophyte-producing cells diverge from the reproductive meristem, a totipotent clump of developing cells in the adult plant that creates all the flower's features (both sexual and asexual structures). Second, meiosis is followed by mitotic divisions and differentiation to create the gametes. In plants, sister, non-gametic cells are connected to the female gametes (the egg cell and the central cell) (the synergids and the antipodal cells). The haploid microspore passes through a mitosis to create a vegetative and generative cell during male gametogenesis. The generative cell undergoes a second mitotic division, resulting in the creation of two.

Premeiotic, post meiotic, pre mitotic, or postmitotic events are all possibilities if imprints are created during male and female gametogenesis. However, if only one of the daughter cells receives parental imprints following mitosis, this would result in two functionally different female gametes or two functionally different sperm cells. Demethylation is seen in the pollen grain following the second meiosis and before to the generative cell's mitosis, as was discussed in the section before this one. Along with pollen differentiation, various structural and compositional DNA alterations also occur. These modifications are potential steps for the genome-wide erasure and/or reprogramming of the imprinting that happens in animals. During the growth of sperm cells, the male DNA is extensively demethylated in plants, whereas the converse is true in animals.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Sources are mixed when using this system of numbering. Some sources use the chromatid number when writing "n" rather than the ploidy number. Hence gametogonium and primary gametocyte would be "4n" rather than "2n" with "4c" for copies. The system used below has been determined by wikipedia consensus and should not necessarily be used as the definitive source on the issue.

References

[edit]- ^ Saitou, Mitinori; Hayashi, Katsuhiko (2021). "Mammalian in vitro gametogenesis". Science. 374 (6563): eaaz6830. doi:10.1126/science.aaz6830. ISSN 1095-9203. PMID 34591639. S2CID 238238458.

- ^ Saitou, Mitinori; Hayashi, Katsuhiko (October 2021). "Mammalian in vitro gametogenesis". Science. 374 (6563): eaaz6830. doi:10.1126/science.aaz6830. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 34591639. S2CID 238238458.

- ^ a b Cohen, Glenn; Daley, George Q.; Adashi, Eli Y. (January 11, 2017). "Disruptive reproductive technologies". Science Translational Medicine. 9 (372): eaag2959. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aag2959. PMID 28077678.

In vitro gametogenesis (IVG)—the generation of eggs and sperm from pluripotent stem cells in a culture dish. Currently feasible in mice, IVG is poised for future success in humans and promises new possibilities for the fields of reproductive and regenerative medicine.

- ^ "Scientists near a breakthrough that could revolutionize human reproduction".

- ^ Harrison CJ, Alvey E, Henderson IR (2010). "Meiosis in flowering plants and other green organisms". J. Exp. Bot. 61 (11): 2863–75. doi:10.1093/jxb/erq191. PMID 20576791.

- ^ Mirzaghaderi G, Hörandl E (2016). "The evolution of meiotic sex and its alternatives". Proc. Biol. Sci. 283 (1838). doi:10.1098/rspb.2016.1221. PMC 5031655. PMID 27605505.

- ^ Harrison, C. Jill; Alvey, Elizabeth; Henderson, Ian R. (2010). "Meiosis in flowering plants and other green organisms". Journal of Experimental Botany. 61 (11): 2863–2875. doi:10.1093/jxb/erq191. ISSN 1460-2431. PMID 20576791.