Rutland

Rutland | |

|---|---|

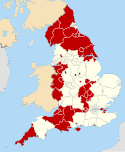

Rutland shown within England | |

| Coordinates: 52°39′N 0°38′W / 52.650°N 0.633°W | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Constituent country | England |

| Region | East Midlands |

| Established | 1204 |

| Established by | Edward the Confessor |

| Time zone | UTC+0 (GMT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) |

| UK Parliament | 1 MP |

| Police | Leicestershire Police |

| Largest town | Oakham |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Lord Lieutenant | Sarah Furness |

| High Sheriff | Geraldine Mary Ethel Feehally |

| Area | 382 km2 (147 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 45th of 48 |

| Population (2022)[1] | 41,151 |

| • Rank | 47th of 48 |

| Density | 108/km2 (280/sq mi) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Unitary authority | |

| Council | Rutland County Council |

| Control | No overall control |

| Admin HQ | Catmose House, Oakham |

| Area | 382 km2 (147 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 89th of 296 |

| Population (2022)[3] | 41,151 |

| • Rank | 294th of 296 |

| Density | 108/km2 (280/sq mi) |

| ISO 3166-2 | GB-RUT |

| GSS code | E06000017 |

| Website | rutland |

Rutland (/ˈrʌtlənd/), sometimes archaically called Rutlandshire,[4] is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It borders Leicestershire to the north and west, Lincolnshire to the north-east, and Northamptonshire to the south-west. Oakham is the largest town and county town.

Rutland has an area of 382 km2 (147 sq mi) and a population of 41,049, the second-smallest ceremonial county population after the City of London. The county is rural, and the only towns are Oakham (12,149) and Uppingham (4,745), both in the west of the county; the largest settlement in the east is the village of Ketton (1,926). For local government Rutland is a unitary authority area. The county was historically the smallest in England, a fact reflected in the motto of the county council: Multum in Parvo, or "much in little".[5]

The geography of Rutland is characterised by low, rolling hills, the highest of which is a 197 m (646 ft) point in Cold Overton Park. In the 1970s a large artificial reservoir, Rutland Water, was created in the centre of the county. It is now a nature reserve, serving as an overwintering site for wildfowl and a breeding site for ospreys. The older buildings in the county are built from local limestone or ironstone, and many have roofs of Collyweston stone slate or thatch.

There is little evidence of Prehistoric settlement in the county, though Roman habitation is suggested by the discovery of a large Roman mosaic and probable farming complex just west of Ketton.[6] It was certainly settled by the Angles from the fifth century and later formed part of Mercia. It is not mentioned as a distinct county until 1179, and during the Domesday Survey was treated as part of Nottinghamshire and Northamptonshire. During the High Middle Ages much of the county was forested and used as hunting grounds, a tradition which continues to the present with packs such as the Cottesmore Hunt. The county's main industry is agriculture, with wool being particularly important in the sixteenth century, and there is a limestone quarry near Ketton. Rutland bitter is a distinctive ale associated with the village of Langham.[7][8][9][10]

Etymology

Rutland is referred to as Roteland in the Domesday Book. The name means "land belonging to Rōta", an Old English personal name.[11][12] Inhabitants of Rutland are traditionally known as "raddlemen", perhaps because the county was once a source of red ochre (also known as raddle).[13]

History

Earl of Rutland and Duke of Rutland are titles in the peerage of England held in the Manners family, derived from the historic county of Rutland. The Earl of Rutland was elevated to the status of Duke in 1703 and the titles were merged. The family seat is Belvoir Castle, Leicestershire.

The office of High Sheriff of Rutland was instituted in 1129, and there has been a Lord Lieutenant of Rutland since at least 1559. Oakham Castle was built c. 1180–1190 and is "one of the nation’s best-preserved Norman buildings" and is a Grade I listed building.[14]

By the time of the 19th century it had been divided into the hundreds of Alstoe, East Rutland, Martinsley, Oakham and Wrandike.

Rutland covered parts of three poor law unions and rural sanitary districts (RSDs): those of Oakham, Uppingham and Stamford. The registration county of Rutland contained the entirety of Oakham and Uppingham RSDs, which included several parishes in Leicestershire and Northamptonshire – the eastern part in Stamford RSD was included in the Lincolnshire registration county. Under the Poor Laws, Oakham Union workhouse was built in 1836–37 at a site to the north-east of the town, with room for 100 paupers. The building later operated as the Catmose Vale Hospital, and now forms part of the Oakham School.[15]

In 1894 under the Local Government Act 1894 the rural sanitary districts were partitioned along county boundaries to form three rural districts. The part of Oakham and Uppingham RSDs in Rutland formed the Oakham Rural District and Uppingham Rural District, with the two parishes from Oakham RSD in Leicestershire becoming part of the Melton Mowbray Rural District, the nine parishes of Uppingham RSD in Leicestershire becoming the Hallaton Rural District, and the six parishes of Uppingham RSD in Northamptonshire becoming Gretton Rural District. Meanwhile, that part of Stamford RSD in Rutland became the Ketton Rural District.

Oakham Urban District was created from Oakham Rural District in 1911. It was subsequently abolished in 1974.[16]

Rutland was included in the "East Midlands General Review Area" of the 1958–67 Local Government Commission for England. Draft recommendations would have seen Rutland split, with Ketton Rural District going along with Stamford to a new administrative county of Cambridgeshire, and the western part added to Leicestershire. The final proposals were less radical and instead proposed that Rutland become a single rural district within the administrative county of Leicestershire.[17]

District of Leicestershire (1974–1997)

Rutland became a non-metropolitan district of Leicestershire under the Local Government Act 1972, which took effect on 1 April 1974. The original proposal was for Rutland to be merged with what is now the Melton borough, as Rutland did not meet the requirement of having a population of at least 40,000. The revised and implemented proposals allowed Rutland to be exempt from this.

Unitary authority (1997–present)

re-establishment in 1997

In 1994, the Local Government Commission for England, which was conducting a structural review of English local government, recommended that Rutland become a unitary authority. This was implemented on 1 April 1997, when Rutland County Council became responsible for almost all local services in Rutland, with the exception of the Leicestershire Fire and Rescue Service and Leicestershire Police, which are run by joint boards with Leicestershire County Council and Leicester City Council. Rutland regained a separate lieutenancy and shrievalty, and thus also regained status as a ceremonial county.

Rutland was a postal county until the Royal Mail integrated it into the Leicestershire postal county in 1974. After a lengthy campaign,[18] and despite counties no longer being required for postal purposes,[19] the Royal Mail agreed to re-create a postal county of Rutland in 2007. This was achieved in January 2008 by amending the former postal county for all of the Oakham (LE15) post town and a small part of the Market Harborough (LE16) post town.[20]

Politics and subdivisions

Rutland County Council

Rutland County Council is a unitary authority and is responsible for almost all local services in Rutland, with the exception of the Leicestershire Fire and Rescue Service and Leicestershire Police, which are run by joint boards with Leicestershire County Council and Leicester City Council.

Following the 2023 council elections, the Liberal Democrats emerged as the largest group and subsequently formed a cabinet led by Gale Waller.[21]

Wards

This section needs to be updated. (August 2024) |

As from the May 2019 elections, there are 27 councillors representing 15 wards on Rutland County Council. They represent a mixture of one, two and three-person wards.

| Parliamentary constituency | Ward | Councillor | Party | Term of office | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rutland and Melton constituency |

Barleythorpe | David Blanksby | Independent | 2019–23 | |

| Sue Webb | Independent | 2019-23 | |||

| Braunston & Martinsthorpe | Edward Baines | Conservative | 2019–23 | ||

| William Cross | Conservative | 2019-23 | |||

| Cottesmore | Samantha Harvey | Conservative | 2019-23 | ||

| Abigail McCartney | Liberal Democrats | 2019–23 | |||

| Exton | June Fox | Conservative | 2016–23 | ||

| Greetham | Nick Begy | Conservative | 2019-23 | ||

| Ketton | Gordon Brown | Conservative | 2019-23 | ||

| Karen Payne | Conservative | 2019–23 | |||

| Langham | Oliver Hemsley | Conservative | 2019-23 | ||

| Lyddington | Andrew Brown | Independent | 2019-23 | ||

| Normanton | Kenneth Bool | Conservative | 2019-23 | ||

| Gale Waller | Liberal Democrats | 2019-23 | |||

| Oakham North East | Jeff Dale | Independent | 2019–23 | ||

| Alan Walters | Independent | 2019-23[22] | |||

| Oakham North West | Paul Ainsley | Conservative | 2019–23 | ||

| Leah Toseland | Labour | 2021-23[23] | |||

| Oakham South | Joanna Burrows | Liberal Democrats | 2019–23 | ||

| Paul Browne | Liberal Democrats | 2022-23 | |||

| Ray Payne | Liberal Democrats | 2022-23 | |||

| Ryhall and Casterton | Richard Coleman | Conservative | 2019-23 | ||

| David Wilby | Conservative | 2019-23 | |||

| Uppingham | Stephen Lambert | Liberal Democrats | 2022-23 | ||

| Marc Oxley | Independent | 2019-23 | |||

| Lucy Stephenson | Conservative | 2019–23 | |||

| Whissendine | Rosemary Powell | Independent | 2019-23 | ||

Parliamentary constituency

Rutland formed a Parliamentary constituency on its own until 1918, when it became part of the Rutland and Stamford constituency, along with Stamford in Lincolnshire. Since 1983 it has formed part of the Rutland and Melton constituency along with Melton borough and part of Harborough district from Leicestershire. Further to the completion of the 2023 Periodic Review of Westminster constituencies, Rutland and Stamford was re-established for the 2024 general election.[24]

As of the 2024 general election, Alicia Kearns of the Conservative Party is the member of parliament for Rutland and Stamford, having received 43.7% of the vote.

Civil parishes

The county comprises 57 civil parishes, which range considerably in size and population, from Martinsthorpe (nil population) to Oakham (10,922 residents in the 2011 census).

Demographics

The population in the 2011 Census was 37,369, a rise of 8% on the 2001 total of 34,563. The population saw a nearly 1% increase in the population at the 2021 Census with a recorded population of 41,049.

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1831 | 19,380 |

| 1861 | 21,861 |

| 1871 | 22,073 |

| 1881 | 21,434 |

| 1891 | 20,659 |

| 1901 | 19,709 |

| 1991 | 33,228 |

| 2001 | 34,560 |

| 2011 | 37,400[25] |

| 2021 | 41.049 |

At the 2021 Census, the demographics for the county were recorded as follow:

Rutland had a recorded population of 41,049 at the 2021 census, an increase from the previous population recorded of 37,369 at the 2011 census and 34,563 at the 2001 census.[26] In the 2021 Census, there was an estimated 21,072 men and 19,977 women living in Rutland.[citation needed]

The county had an ethnicity makeup at the 2021 Census of:

The county's religious makeup at the 2021 Census was:

- 55.4% Christianity - 22,728

- 37.1% no religion - 15,239

- 0.6% Islam - 258

- 0.2% Sikhism - 67

- 0.3% Hinduism - 125

- 0.4% Buddhism - 150

- 0.1% Judaism - 53

- 0.5% other - 201

- 5.4% not stated - ???

In 2006 it was reported that Rutland has the highest fertility rate of any English county – the average woman having 2.81 children, compared with only 1.67 in Tyne and Wear.[27]

In December 2006, Sport England published a survey which revealed that residents of Rutland were the 6th most active in England in sports and other fitness activities. 27.4% of the population participate at least 3 times a week for 30 minutes.[28]

In 2012, the well-being report by the Office for National Statistics[29] found Rutland to be the "happiest county" in the mainland UK.[30]

Geography

The particular geology of the area has given its name to the Rutland Formation, which was formed from muds and sand carried down by rivers and occurring as bands of different colours, each with many fossil shells at the bottom. The formation has also preserved a well-preserved specimen of the sauropod dinosaur Cetiosaurus oxienensis[31] at Great Casterton, currently on display at Leicester Museum & Art Gallery. At the bottom of the Rutland Formation is a bed of dirty white sandy silt. Under the Rutland Formation is a formation called the Lincolnshire limestone. The best exposure of this limestone (and also the Rutland Formation) is at the Ketton Cement Works quarry just outside Ketton.[32]

Rutland is dominated by Rutland Water, a large artificial lake formerly known as "Empingham Reservoir", in the middle of the county, which is almost bisected by the Hambleton Peninsula. The west part is in the Vale of Catmose. Rutland Water, when construction started in 1971, became Europe's largest man-made lake; construction was completed in 1975, and filling the lake took a further four years. This has been voted Rutland's favourite tourist attraction.

The highest point of the county is at Cold Overton Park (historically part of Flitteriss Park) at 197 m (646 ft) above sea level close to the west border (OS Grid reference: SK8271708539). The lowest point is close to the east border, in secluded farmland at North Lodge Farm, northeast of Belmesthorpe, at just 17 m (56 feet) above sea level (OS Grid reference: TF056611122); this corner of the county is on the edge of The Fens and is drained by the West Glen.

Rivers

Economy

There are 17,000 people of working age in Rutland, of which the highest percentage (30.8%) work in Public Administration, Education and Health, closely followed by 29.7% in Distribution, Hotels and Restaurants and 16.7% in Manufacturing industries. Significant employers include Lands' End in Oakham and the Ketton Cement Works. Other employers in Rutland include two Ministry of Defence bases – Kendrew Barracks (formerly RAF Cottesmore) and St George's Barracks (previously RAF North Luffenham), two public schools – Oakham and Uppingham – and one prison, Stocken. The former Ashwell prison closed at the end of March 2011 after a riot and government review but, having been purchased by Rutland County Council, has now been turned into Oakham Enterprise Park. The county used to supply iron ore to Corby steel works but these quarries closed in the 1960s and early 1970s resulting in the famous walk of "Sundew" (the Exton quarries' large walking dragline) from Exton to Corby, which even featured on the children's TV series Blue Peter. Agriculture thrives with much wheat farming on the rich soil. Tourism continues to grow.

The Ruddles Brewery was Langham's biggest industry until it was closed in 1997. Rutland bitter is one of only three UK beers to have achieved Protected Geographical Indication status; this followed an application by Ruddles. When Greene King, the owners of Ruddles, closed the Langham brewery it was unable to take advantage of the registration.[33] However, in 2010 a Rutland Bitter was launched by Oakham's Grainstore Brewery.[34]

It is 348th out of 354 on the Indices of Deprivation for England, showing it to be one of the least economically deprived areas in the country.[35]

In March 2007, Rutland became only the fourth Fairtrade County.

This is a chart of trend of regional gross value added of the non-metropolitan county of Leicestershire and Rutland at current basic prices with figures in millions of British Pounds Sterling.[36]

| Year | Regional Gross Value Added[1] | Agriculture[2] | Industry[3] | Services[4] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 6,666 | 145 | 2,763 | 3,758 |

| 2000 | 7,813 | 112 | 2,861 | 4,840 |

| 2003 | 9,509 | 142 | 3,045 | 6,321 |

^ includes hunting and forestry

^ includes energy and construction

^ includes financial intermediation services indirectly measured

^ Components may not sum to totals due to rounding

As far as the NHS is concerned Rutland is generally treated as part of Leicestershire.

Transport

A small part of the East Coast Main Line passes through Rutland's north-east corner, near Essendine. It was on this stretch that a train pulled by the locomotive Mallard set the world speed record for steam locomotives on 3 July 1938, with a speed of 125.55 mph (202.05 km/h).

Rutland was the last county in England without a direct rail service to London (apart from the Isle of Wight and several administrative counties which are unitary authorities). East Midlands Trains started running a single service from Oakham railway station to London St Pancras via Corby on 27 April 2009.[37]

Through the Rutland Electric Car Project, Rutland was the first county to offer a county-wide public electric-vehicle charging network.[38]

In popular culture

Rutland's small size has led to a number of humorous references such as Rutland Weekend Television, a television comedy sketch series hosted by Eric Idle. The county is the supposed home of the parody rock band The Rutles, who first appeared on Rutland Weekend Television.

The events in several Peter F. Hamilton books (including Misspent Youth and Mindstar Rising) are situated in Rutland, where the author lives. Adam Croft is writing the Rutland crime series, beginning with What Lies Beneath (2020).

Rutland was the last county in England without a McDonald's restaurant.[39] However, in January 2020 a planning application for a McDonald's restaurant on the outskirts of Oakham was approved by the County Council[40] and the restaurant opened on 4 November 2020.[41]

Traditions

Rutland's traditions include:

- Letting of the Banks (Whissendine): The Banks are pasture land and the letting traditionally occurs in the third week of March

- Rush Bearing and Rush Strewing (Barrowden): Reeds are gathered in the church meadow on the eve of St Peter's Day and placed on the church floor (late June, early July)

- Uppingham Market was granted by Charter in 1281 by Edward I.

- According to tradition, any royalty or peers passing through Oakham must present a horseshoe to the Lord of the Manor of Oakham. The horseshoe has been Rutland's emblem for hundreds of years.

Education

Harington School provides post-16 education in the county. Rutland County College closed in 2017.

Places of interest

- Barnsdale Gardens

- Lyddington Bede House

- Oakham Castle

- Rutland County Museum, Oakham

- Rutland Railway Museum, Ashwell

- Rutland Water

- Tolethorpe Hall

- The Viking Way

- Rutland Water Nature Reserve

See also

- Flag of Rutland

- High Sheriff of Rutland

- List of birds of Leicestershire and Rutland

- Lord Lieutenant of Rutland

- Kesteven

- Parts of Holland

- Soke of Peterborough

References

- ^ "Mid-2022 population estimates by Lieutenancy areas (as at 1997) for England and Wales". Office for National Statistics. 24 June 2024. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ^ UK Census (2021). "2021 Census Area Profile – Rutland Local Authority (E06000017)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 12 June 2024.

- ^ "Mid-Year Population Estimates, UK, June 2022". Office for National Statistics. 26 March 2024. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ Hill, John Harwood (1871). Notes on Rutlandshire: A Paper Read Before the Northamptonshire and Leicestershire Architectural Societies at Their Annual Meeting Held on the 6th Day of June 1871 at Uppingham. Ward.

- ^ Scott-Giles, C Wilfrid (1953). Civic Heraldry of England and Wales, 2nd edition. London: J M Dent & Sons. p. 318.

- ^ "Extraordinary Roman Mosaic and Villa Discovered Beneath Farmer's Field in Rutland, East Midlands". Historic England. 25 November 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 943–945.

- ^ "Rutland: General introduction". British History Online. Retrieved 29 June 2023.

- ^ "Rutland | History & Smallest County | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 29 June 2023.

- ^ "Ketton Quarry | Leicestershire and Rutland Wildlife Trust". www.lrwt.org.uk. Retrieved 29 June 2023.

- ^ Mills, A. D. (2011). "Rutland". A Dictionary of British Place Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191739446.

- ^ Watts, Victor, ed. (2010). The Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names. Cambridge University Press. p. 514. ISBN 978-0-521-16855-7.

- ^ "raddleman". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OED/4736999989. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Historic England. "Oakham Castle (Grade I) (1073277)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ "Workhouses website". Archived from the original on 6 October 2007.

- ^ "Relationships / unit history of OAKHAM". www.visionofbritain.org.uk. Archived from the original on 23 September 2006.

- ^ Little Rutland To Go It Alone – No Merger with Leicestershire. The Times, 2 August 1963.

- ^ Stamford Mercury, MP wins seven-year postal address battle Archived 17 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine, 5 November 2007.

- ^ Royal Mail, Postcode Address File Code of Practice, (2004) [dead link]

- ^ AFD Software – Latest PAF Data News Archived 21 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Lib Dems dominate new Rutland Council Cabinet | Local News | News | Oakham Nub News". 22 May 2023. Archived from the original on 22 May 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ "Councillor quits Tory party on election night". 5 November 2021. Archived from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ "Rutland County Council ELECTION OF COUNCILLORS FOR THE OAKHAM NORTH WEST WARD - DECLARATION OF RESULT OF POLL" (PDF). 1 March 2022. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2021.

- ^ "The 2023 Review of Parliamentary Constituency Boundaries in England – Volume one: Report – East Midlands | Boundary Commission for England". boundarycommissionforengland.independent.gov.uk. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ "Rutland County Council: Census and Population Information". Archived from the original on 2 August 2012.

- ^ "Rutland (Unitary District, Rutland, United Kingdom) - Population Statistics, Charts, Map and Location". www.citypopulation.de. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ^ "UK Government Web Archive". webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 7 March 2023. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ "Sports England". Archived from the original on 25 February 2010.

- ^ "UK Government Web Archive". webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 10 January 2013.

- ^ "ONS well-being report reveals UK's happiness ratings". 24 July 2012. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ Upchurch, Paul; Martin, John (November 2002). "The Rutland Cetiosaurus: the anatomy and relationships of a Middle Jurassic British sauropod dinosaur". Palaeontology. 45 (6): 1049–1074. Bibcode:2002Palgy..45.1049U. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00275. ISSN 0031-0239.

- ^ "The Geology of the Peterborough Area". Peterborough RIGS. Archived from the original on 24 February 2006. Retrieved 3 October 2006.

- ^ "Commission Regulation (EC) No 1107/96 of 12 June 1996 on the registration of geographical indications and designations of origin under the procedure laid down in Article 17 of Council Regulation (EEC) No 2081/92". EUR-LEX Access to European Law. European Commission. 12 June 1996. Archived from the original on 9 October 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ^ ""Rutland Bitter resurrected" Leicester Mercury 1 Oct 2010". Archived from the original on 17 September 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ "Geographical Statistical Information". Government Office for the East Midlands. Archived from the original on 9 October 2006. Retrieved 3 October 2006.

- ^ National Accounts Co-ordination Division (21 December 2005). "Regional Gross Value Added" (PDF). Office for National Statistics. pp. 240–253. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 December 2007. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ^ "Corby train delays labelled 'shambolic'". Northants Evening Telegraph. 25 November 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Rutland establishes public EV charging network". EVFleetWorld. 9 March 2012. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ Pittam, David (16 September 2019). "Rutland: England's only county without a McDonald's". BBC News. Archived from the original on 16 September 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- ^ Gayle, Damien (14 January 2020). "Rutland falls to the golden arches and welcomes McDonald's". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ Troughton, Adrian (3 November 2020). "First McDonald's restaurant in Rutland opening its doors". LeicestershireLive. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

Bibliography

- Phillips, George (1912). Cambridge County Geography of Rutland. University Press. ASIN B00085ZZ5M.

- Rycroft, Simon; Roscoe, Barbara; Rycroft, Simon (1996). "Landscape and Identity at Ladybower Reservoir and Rutland Water". Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 21 (3). Blackwell Publishing: 534–551. Bibcode:1996TrIBG..21..534C. doi:10.2307/622595. JSTOR 622595.

- Galitzine, Prince Yuri (1986). Domesday book in Rutland: The Dramatis personae (PDF). Rutland Record Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 January 2012.

External links

Rutland travel guide from Wikivoyage

Rutland travel guide from Wikivoyage- Rutland County Council

- Rutland Local History & Record Society