Peter Weir

Peter Weir | |

|---|---|

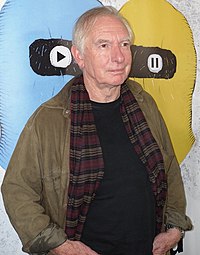

Weir in 2011 | |

| Born | Peter Lindsay Weir 21 August 1944 Sydney, Australia |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1967–2010 |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2 |

| Signature | |

| |

Peter Lindsay Weir AM (/wɪər/ WEER; born 21 August 1944) is an Australian retired film director. He is known for directing films crossing various genres over forty years with films such as Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), Gallipoli (1981), The Year of Living Dangerously (1982), Witness (1985), Dead Poets Society (1989), Fearless (1993), The Truman Show (1998), Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2003), and The Way Back (2010). He has received six Academy Award nominations. In 2022 he was awarded the Academy Honorary Award for his lifetime achievement career.[1] In 2024, he received an honorary life-time achievement award at the Venice Film Festival (Golden Lion).[2]

Early in his career as a director, Weir was a leading figure in the Australian New Wave cinema movement (1970–1990). Weir made his feature film debut with Homesdale and continued with the mystery drama Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), the supernatural thriller The Last Wave (1977) and the historical drama Gallipoli (1981). Weir gained tremendous success with the multinational production The Year of Living Dangerously (1982).

After the success of The Year of Living Dangerously, Weir directed a diverse group of American and international films covering most genres–many of them major box office hits–including Academy Award-nominated films such as the thriller Witness (1985), the drama Dead Poets Society (1989), the romantic comedy Green Card (1990), the social science fiction comedy-drama The Truman Show (1998) and the epic historical drama Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2003). His final feature before his retirement was the well-received The Way Back (2010).

Early life and education

[edit]Peter Lindsay Weir was born in Sydney, in 1944, the son of Peggy (née Barnsley Sutton) and Lindsay Weir, a real estate agent.[3] Weir attended The Scots College and Vaucluse Boys High School before studying arts and law at the University of Sydney. His interest in film was sparked by him meeting fellow students, including Phillip Noyce and the future members of the Sydney filmmaking collective Ubu Films.[4]

Career

[edit]1960s

[edit]After leaving university in the mid-1960s, he joined Sydney television station ATN-7, where he worked as a production assistant on the groundbreaking satirical comedy program The Mavis Bramston Show. During this period, using station facilities, Weir made his first two experimental short films, Count Vim's Last Exercise and The Life and Flight of Reverend Buck Shotte.[4]

In 1969, the founders of Producers Authors Composers and Talent (now PACT Centre for Emerging Artists) attended a Sydney University Architecture Revue, with sets by Geoffrey Atherden and Grahame Bond. They invited Bond, Atherden, Weir, and Weir's friend, composer Peter Best, a chance to do a show at the National Art School. Sir Robert Helpmann saw the show and took it to the Adelaide Festival. Soon afterward Weir and Best were commissioned to write a Christmas special TV show for ABC Television titled Man on a Green Bike.[5]

1970s

[edit]Weir took a position with the Commonwealth Film Unit (later renamed Film Australia),[6] for which he made several documentaries, including a short documentary about an underprivileged outer Sydney suburb, Whatever Happened to Green Valley, in which residents were invited to make their own film segments.[4] Another notable film in this period was the short rock music performance film Three Directions in Australian Pop Music (1972), which featured in-concert colour footage of three of the most significant Melbourne rock acts of the period, Spectrum, The Captain Matchbox Whoopee Band, and Wendy Saddington. He also directed one section of the three-part, three-director feature film 3 to Go (1970), which won an AFI award.[7][4]

After leaving the CFU, Weir made his first major independent film, the short feature Homesdale (1971), an offbeat black comedy. It co-starred rising young actress Kate Fitzpatrick and musician and comedian Grahame Bond, who came to fame in 1972 as the star of The Aunty Jack Show; Weir also played a small role, but this was to be his last significant screen appearance.[4]

Weir's first full-length feature film was the underground cult classic, The Cars That Ate Paris (1974), a low-budget black comedy about the inhabitants of a small country town who deliberately cause fatal car crashes and live off the proceeds. It was a minor success in cinemas but proved very popular on the then-thriving drive-in circuit.[4] The plot had been inspired by a press report Weir had read about two young English women who had vanished while on a driving holiday in France. With this film, along with the earlier Homesdale, Weir set the basic thematic pattern which has persisted throughout his career: nearly all his feature films deal with people who face some form of crisis after finding themselves isolated from society in some way – either physically (Witness, The Mosquito Coast, The Truman Show, Master and Commander), socially/culturally (Picnic at Hanging Rock, The Last Wave, Dead Poets Society, Green Card), or psychologically (Fearless).[8]

Weir's major breakthrough in Australia and internationally was the lush, atmospheric period mystery Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), made with substantial backing from the state-funded South Australian Film Corporation and filmed on location in South Australia and rural Victoria. Based on the novel by Joan Lindsay and set at the turn of the 20th century, the film relates the purportedly "true" story of a group of students from an exclusive girls' school who mysteriously vanish from a school picnic on Valentine's Day 1900. Widely credited as a key work in the "Australian film renaissance" of the mid-1970s, Picnic was the first Australian film of its era to gain both critical praise and be given substantial international theatrical releases. It also helped launch the career of internationally renowned Australian cinematographer Russell Boyd. It was widely acclaimed by critics, many of whom praised it as a welcome antidote to the so-called "ocker film" genre, typified by The Adventures of Barry McKenzie and Alvin Purple.[citation needed]

Weir's next film, The Last Wave (1977), was a supernatural thriller about a man who begins to experience terrifying visions of an impending natural disaster. It starred American actor Richard Chamberlain, who was well known to Australian and world audiences as the eponymous physician in the popular Dr. Kildare TV series. He later starred in the major series The Thorn Birds, set in Australia. The Last Wave was a pensive, ambivalent work that expanded on themes from Picnic, exploring the interactions between the native Aboriginal and European cultures. It co-starred the Aboriginal actor David Gulpilil, whose performance won the Golden Ibex (Oscar equivalent) at the Tehran International Festival in 1977, but it was only a moderate commercial success at the time.[9]

Between The Last Wave and his next feature, Weir wrote and directed the offbeat low-budget telemovie The Plumber (1979).[10] It starred Australian actors Judy Morris and Ivar Kants and was filmed in three weeks.[11] Inspired by an account told to him by friends, it is a black comedy about a woman whose life is disrupted by a subtly menacing plumber.

1980s

[edit]Weir scored a major Australian hit and further international praise with his next film, the historical adventure-drama Gallipoli (1981). Scripted by the Australian playwright David Williamson, it is regarded as classic Australian cinema. Gallipoli was instrumental in making Mel Gibson (Mad Max) into a major star, although his co-star Mark Lee, who also received high praise for his role, has made relatively few screen appearances since.[citation needed]

The climax of Weir's early career was the $6 million multi-national production The Year of Living Dangerously (1982), again starring Gibson, playing opposite top Hollywood female lead Sigourney Weaver in a story about journalistic loyalty, idealism, love and ambition in the turmoil of Sukarno's Indonesia of 1965. It was an adaptation of the novel by Christopher Koch, which was based in part on the experiences of Koch's journalist brother Philip, the ABC's Jakarta correspondent and one of the few western journalists in the city during the 1965 attempted coup. The film also won Linda Hunt (who played a man in the film) an Oscar for Best Actress in a Supporting Role. The film was again produced by Hal and Jim McElroy, who had also produced Weir's first three films, The Cars That Ate Paris, Picnic at Hanging Rock and The Last Wave.[citation needed]

Weir's first American film was the successful thriller Witness (1985), the first of two films he made with Harrison Ford, about a boy who sees the murder of an undercover police officer by corrupt coworkers and has to be hidden in his Amish community to protect him. Weir directed Ford in his only performance to receive an Academy Award nomination, while child star Lukas Haas also received wide praise for his debut film performance. Witness also earned Weir his first Academy Award nomination as Best Director, and was his first of several films to be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture, it later won 2 for Best Film Editing & Best Original Screenplay.[12]

It was followed by the darker, less commercial The Mosquito Coast (1986), Paul Schrader's adaptation of Paul Theroux's novel. Ford played a man obsessively pursuing his dream to start a new life in the Central American jungle with his family. These dramatic parts provided Harrison Ford with important opportunities to break the typecasting of his career-making roles in the Star Wars and Indiana Jones series. Both films showed off his ability to play more subtle and substantial characters and he was nominated for a Best Actor Oscar for his work in Witness, the only Academy Awards recognition in his career. The Mosquito Coast is also notable for a performance by the young River Phoenix.[citation needed]

Weir's next film, Dead Poets Society, was a major international success, with Weir again receiving credit for expanding the acting range of its Hollywood star. Robin Williams was mainly known for his anarchic stand-up comedy and his popular TV role as the wisecracking alien in Mork & Mindy; in this film he played an inspirational teacher in a dramatic story about conformity and rebellion at an exclusive New England prep school in the 1950s. The film was nominated for four Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director for Weir. It won Best Original Screenplay and launched the acting careers of young actors Ethan Hawke and Robert Sean Leonard. It became a major box-office hit and is one of Weir's best-known films to mainstream audiences.[citation needed]

1990s

[edit]Weir's first romantic comedy Green Card (1990) was another casting risk. Weir chose French screen icon Gérard Depardieu in the lead—Depardieu's first English-language role—and paired him with American actress Andie MacDowell. Green Card was a box-office hit but was regarded as less of a critical success, although it helped Depardieu's path to international fame. Weir received an Oscar nomination for his original screenplay.[13]

Fearless (1993) returned to darker themes and starred Jeff Bridges as a man who believes he has become invincible after surviving a catastrophic air crash. Though well reviewed, particularly the performances of Bridges and Rosie Perez—who received an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress—the film was less commercially successful than Weir's two preceding films. It was entered into the 44th Berlin International Film Festival.[14]

After five years, Weir returned to direct his biggest success to date, The Truman Show (1998), a fantasy-satire of the media's control of life starring Jim Carrey. The Truman Show was both a box office and a critical success, receiving positive reviews and numerous awards, including three Academy Award nominations: Andrew Niccol for Best Original Screenplay, Ed Harris for Best Actor in a Supporting Role, and Weir himself for Best Director.[15] In addition to the Academy Award nominations, the film won the 1999 Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation.[16]

2000s

[edit]In 2003, Weir returned to period dramas with Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World, starring Russell Crowe. A screen adaptation from various episodes in Patrick O'Brian's blockbuster adventure series set during the Napoleonic Wars,[17] the film was well received by critics, but only mildly successful with mainstream audiences.[18][19] Despite another nomination for Best Picture and winning two Oscars—for frequent collaborator Russell Boyd's cinematography and for sound effects editing—the film's box office success was moderate ($93 million at the North American box office).[20] The film grossed slightly better overseas, gleaning an additional $114 million.

Weir had developed several other projects in the 2000s that never came to fruition, including an adaptation of The War Magician with actor Tom Cruise, an adaptation of Robert Kurson's novel Shadow Divers, early development of a proposed Shantaram film starring Johnny Depp, and an adaptation of William Gibson's sci-fi novel Pattern Recognition.[21]

2010s

[edit]In 2010, Weir resurfaced with the historical epic The Way Back,[22] about escapees from a Soviet gulag. The film, while generally well-received critically, was not a financial success.[23][24]

In 2012, it was reported that Weir would direct his own adapted script of Jennifer Egan's gothic thriller The Keep the following year and shoot in Europe. Weir described the project as, "Basically, ... a studio-shoot movie."[25][26] As the years passed, however, without an official announcement, he started to be described as "retired".

2020s

[edit]Speaking in July 2022, speculating about Weir's unannounced retirement, Ethan Hawke said, "I think [Weir] lost interest in movies. He really enjoyed that work when he didn't have actors giving him a hard time. Russell Crowe and Johnny Depp broke him."[27]

In November 2022, Weir received an Academy Honorary Award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.[28]

On the occasion of this award, he also gave his first interview in many years, to The Sydney Morning Herald. In the interview, he said Hawke's quote "must have been taken out of context. I find it puzzling." However, Weir confirmed his retirement, saying that "for film directors, like volcanoes, there are three major stages: active, dormant and extinct. I think I've reached the latter! Another generation is out there calling "action" and "cut" and good luck to them." He stated that he has enjoyed visiting ancient ruins and battlefields and diving on the WWII shipwrecks of the Truk Lagoon during his retirement.[29]

Personal life

[edit]On 14 June 1982, Weir was appointed a Member of the Order of Australia (AM) for his service to the film industry.[30]

Filmography

[edit]| Year | Title | Distributor |

|---|---|---|

| 1971 | Homesdale | |

| 1974 | The Cars That Ate Paris | British Empire Films |

| 1975 | Picnic at Hanging Rock | |

| 1977 | The Last Wave | United Artists |

| 1981 | Gallipoli | Village Roadshow / Paramount Pictures |

| 1982 | The Year of Living Dangerously | United International Pictures / MGM/UA Entertainment Company |

| 1985 | Witness | Paramount Pictures |

| 1986 | The Mosquito Coast | Warner Bros. |

| 1989 | Dead Poets Society | Buena Vista Pictures |

| 1990 | Green Card | |

| 1993 | Fearless | Warner Bros. |

| 1998 | The Truman Show | Paramount Pictures |

| 2003 | Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World | 20th Century Fox |

| 2010 | The Way Back | Newmarket Films / Exclusive Film Distribution / Meteor Pictures |

Awards and nominations

[edit]| Year | Title | Academy Awards | BAFTA Awards | Golden Globe Awards | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominations | Wins | Nominations | Wins | Nominations | Wins | ||

| 1975 | Picnic at Hanging Rock | 3 | 1 | ||||

| 1981 | Gallipoli | 1 | |||||

| 1982 | The Year of Living Dangerously | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 1985 | Witness | 8 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 6 | |

| 1986 | The Mosquito Coast | 2 | |||||

| 1989 | Dead Poets Society | 4 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 4 | |

| 1990 | Green Card | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | ||

| 1993 | Fearless | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 1998 | The Truman Show | 3 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 3 | |

| 2003 | Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World | 10 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 3 | |

| 2010 | The Way Back | 1 | |||||

| Total | 29 | 6 | 32 | 11 | 27 | 5 | |

References

[edit]- ^ "THE ACADEMY TO HONOR MICHAEL J. FOX, EUZHAN PALCY, DIANE WARREN AND PETER WEIR WITH OSCARS® AT GOVERNORS AWARDS IN NOVEMBER". oscars.org. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 8 August 2022. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ^ "Reuters". Reuters. Retrieved 7 September 2024.

- ^ "Peter Weir Biography (1944–)". Film Reference.

...born August 8 (some sources cite June 21), 1944...

- ^ a b c d e f Sutherland, Romy (February 2005). "Weir, Peter – Senses of Cinema". Senses of Cinema.

- ^ Blake, Elissa (14 October 2014). "PACT Centre for Emerging Artists celebrates 50 years". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ "Peter Weir". Britannica. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ "New Australian Directors of the 1970s – The New Wave Directors". Ozflicks. 7 January 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

- ^ Joyaux, Daniel (18 November 2022). "This Must Not Be the Place: The Films of Peter Weir". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

- ^ "Film Victoria" (PDF). 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2024.

- ^ Jackson, Camilla (26 February 2015). "The Dreadful Ten: Camilla's Top Ten Forgotten Australian Horrors". FANGORIA. Archived from the original on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ "The Plumber (TV Movie 1979) – Trivia". Archived from the original on 2 May 2023 – via IMDb.

- ^ Smith, Jeremy (23 May 2022). "It Took A Total Re-Write To Make Witness An Oscar Winner". /Film. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1992". BAFTA. 1992. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ "Berlinale: 1994 Programme". berlinale.de. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ "The 71st Academy Awards | 1999". Oscars.org | Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. 18 November 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ "1999 Hugo Awards". The Hugo Awards. 26 July 2007. Archived from the original on 7 May 2011. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ French, Philip (22 November 2003). "Command performance". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ "Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2003)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ "Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 28 September 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ^ Fuster, Jeremy (13 November 2018). "'Master and Commander': 15th Anniversary of the Franchise That Never Was". TheWrap. Retrieved 17 May 2023.

- ^ Bell, Christopher (12 January 2011). "Peter Weir Teases 3 Projects That Fell Apart In The '00s; Here's What They Might Be". IndieWire.

- ^ "Peter Weir find his 'Way Back': Australian helmer to write, direct fact-based film – Variety". Archived from the original on 9 June 2009. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ "The Way Back (2011)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ "Empire's The Way Back Movie Review". Empireonline.com. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ Dang, Simon (20 May 2012). "Peter Weir Returns With Adaptation Of Jennifer Egan's Contemporary Gothic Thriller 'The Keep'". IndieWire. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- ^ Trumbore, Dave (21 May 2012). "Peter Weir to Direct Adaptation of Contemporary Gothic Thriller THE KEEP". Collider. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- ^ "Ethan Hawke Says Filmmaker Peter Weir Retired After Johnny Depp 'Broke Him'". Newsweek. 20 July 2022. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ^ "Honorary Oscar awards celebrate Fox, Weir, Warren and Palcy". ABC News.

- ^ "From Hitchcock and Hanging Rock to Hollywood: Peter Weir reflects on his brilliant career". 20 November 2022.

- ^ It's an Honour Archived 26 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine – Member of the Order of Australia

Further reading

[edit]- Peter Weir Pays Witness to the Amish – 27 January 1985

- Peter Weir: In a Class by Himself – 4 June 1989

- Poetry Man – Premiere magazine Interview – July 1989

- A Director Asks for Odd and Gets It – 13 October 1993

- Staring Death in the Face – 17 October 1993

- Weir'd Tales – An interview with Peter Weir – 1994

- A Weir'd Experience – 20 April 1998

- Director Tries a Fantasy As He Questions Reality – 21 May 1998

- Interview – Peter Weir – 3 June 1998

- More to Digest than Popcorn: An Interview with Peter Weir – 4 June 1998

- Peter Weir: The Hollywood Interview – 15 March 2008

- Uncommon Man – The DGA Quarterly Interview – Summer 2010

External links

[edit]- 1944 births

- Australian film directors

- Best Director BAFTA Award winners

- Commanders of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland

- Filmmakers who won the Best Film BAFTA Award

- English-language film directors

- European Film Awards winners (people)

- Hugo Award winners

- Living people

- Members of the Order of Australia

- People educated at Scots College (Sydney)

- Film directors from Sydney

- Sydney Law School alumni

- University of Sydney alumni

- Academy Honorary Award recipients

- Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement recipients