Black-headed bunting

| Black-headed bunting | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult male (Lesbos, Greece) | |

| |

| Female (Maharashtra, India) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Emberizidae |

| Genus: | Emberiza |

| Species: | E. melanocephala

|

| Binomial name | |

| Emberiza melanocephala Scopoli, 1769

| |

| |

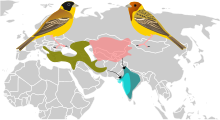

| Breeding and winter distribution ranges of Black-headed and Red-headed Bunting | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The black-headed bunting (Emberiza melanocephala) is a passerine bird in the bunting family Emberizidae. It breeds in south-east Europe east to Iran and migrates in winter mainly to India, with some individuals moving further into south-east Asia. Like others in its family, it is found in open grassland habitats where they fly in flocks in search of grains and seed. Adult males are well marked with yellow underparts, chestnut back and a black head. Adult females in breeding plumage look like duller males. In other plumages, they can be hard to separate from the closely related red-headed bunting and natural hybridization occurs between the two species in the zone of overlap of their breeding ranges in northern Iran.

Taxonomy

[edit]The black-headed bunting was formally described in 1769 by the Austrian naturalist Giovanni Antonio Scopoli under the binomial name Emberiza melanocephala.[2] The type locality is Carniola in Slovenia.[3] The species is monotypic: no subspecies are recognised.[4] The genus name Emberiza is from Old German Embritz, a bunting, and the specific melanocephala combines the Ancient Greek melas meaning "black", and kephale meaning "head".[5]

Description

[edit]This bird is 15 cm (5.9 in) long, larger than a reed bunting, and with a long-tail. The breeding male has bright yellow underparts, chestnut upperparts and a black hood. The female is a washed-out version of the male, with paler underparts, a grey-brown back and a greyish head. The juvenile is similar but the vent is yellow, and both can be difficult to separate from the corresponding plumages of the closely related red-headed bunting although the black-headed tends to have the cheeks darker than the throat. First year males have a grey crown and the back has patches of chestnut and grey. First year females can be difficult to separate from female red-headed buntings although having more streaking on the crown than on the lower back. The vent is yellow.[6]

The black- and red-headed buntings represent sister species which forms a clade along with the crested bunting.[7]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The black-headed bunting breeds in open scrubby areas including agricultural land. In winter they move to Asia and large flocks are found in agricultural fields and grasslands. The longest migration noted from a ringed individual is about 7,000 km. Another ringed bird was determined to have flown 1,000 km in seven days. Males form pure flocks during migration and arrive in the winter quarters well before the females.[8] The winter range within India is mainly in western and northern India extending south to northern Karnataka.[9] In winter they form large communal roosts in thorny acacia trees, often joining other species such as the yellow-throated sparrow.[8]

The main breeding zone extends from south-eastern Europe to central Asia. The wintering grounds are mainly in India although vagrants have been found wintering as far east as Japan, China, Hong Kong, Thailand, Laos, South Korea and Malaysia.[10] Summer vagrants may occur as far north in Europe as Norway.

Behaviour and ecology

[edit]

The black-headed bunting is found in flocks as it forages on grasslands for seeds. They breed in summer, building a nest in a low bush or on the ground. The nest is a cup made of dry grass and lined with hair.[11] The clutch consists of four to six eggs. The eggs hatch after about 13 days and the chicks fledge after about 10 days. Its natural food consists of insects when feeding young, and otherwise seeds. In Bulgaria, the collapse of the drying cotton thistle (Onopordum acanthium) stems on which the birds build their nests has caused high mortality; this is thought to be an example of an ecological trap.[12] In northern Iran, there is a region of range overlap with the red-headed bunting and natural hybrids are common[13] although molecular data indicates that there is considerable genetic divergence between the two species.[14]

Like the red-headed bunting but unlike many other Emberiza buntings, it has two moults in a year. It undergoes one moult in the winter quarters prior to migrating back to the breeding region, and another after breeding. Young birds fledge with a soft plumage and then moult into a juvenile plumage before migrating and then assume an adult plumage after moulting in their winter quarters.[8][15]

In winter their call is a single note tweet or soft zrit.[8] The song consists of a loud series of strophes each made up a high harsh notes that accelerate into a jangling mix with some clear slurred notes interspersed before stopping abruptly.[6]

Gallery

[edit]-

Breeding male, Belo Polje, Serbia

-

Breeding male, Serbia

-

Baga, Goa, India

References

[edit]- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Emberiza melanocephala". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22720990A89314245. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22720990A89314245.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Scopoli, Giovanni Antonio (1769). Annus Historico-Naturalis (in Latin). Vol. Part 1. Lipsiae [Leipzig]: Sumtib. C.G. Hilscheri. p. 142.

- ^ Paynter, Raymond A. Jr, ed. (1970). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 13. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 27.

- ^ Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (2020). "Sylviid babblers, parrotbills, white-eyes". IOC World Bird List Version 11.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London, United Kingdom: Christopher Helm. pp. 145, 246. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ a b Rasmussen, Pamela C.; Anderton, John C. (2012). Birds of South Asia. The Ripley Guide. Vol. 2: Attributes and Status (2nd ed.). Washington D.C. and Barcelona: Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History and Lynx Edicions. p. 556. ISBN 978-84-96553-87-3.

- ^ Alström, P; Olsson, U; Lei, F; Wang H; Gao, W; Sundberg, P (2008). "Phylogeny and classification of the Old World Emberizini (Aves, Passeriformes)" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 47 (3): 960–973. Bibcode:2008MolPE..47..960A. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.12.007. PMID 18411062.

- ^ a b c d Ali, S & Ripley, SD (1999). Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan. Volume 10 (2nd ed.). New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 217–219.

- ^ Gururaja, KV (1999). "Sighting of Black-headed Bunting Emberiza melanocephala in Shimoga city". Newsletter for Birdwatchers. 39 (1): 14.

- ^ Dymond, N (1999). "Two records of Black-headed Bunting Emberiza melanocephala in Sabah- the first definite occurrence in Malaysia and Borneo" (PDF). Forktail. 15: 102. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2011.

- ^ Dresser, HE (1902). A manual of Palaearctic birds. Part 1. London: Published by the author. pp. 346–347.

- ^ Antonov, A; Stokke, BG; Moksnes, A & E Røskaft (2008). "Unusually high losses to nest collapse in black-headed buntings Emberiza melanocephala nesting on a preferred plant species". Bird Study. 55 (2): 233–235. Bibcode:2008BirdS..55..233A. doi:10.1080/00063650809461527. S2CID 85017756.

- ^ Randler, C. (2006). "Behavioural and ecological correlates of natural hybridization in birds". Ibis. 148 (3): 459–467. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2006.00548.x.

- ^ Aliabadian, M.; Kaboli, M.; Nijman, V.; Vences, M. (2009). "Molecular identification of birds: performance of distance-based DNA barcoding in three genes to delimit parapatric species". PLOS ONE. 4 (1): e4119. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.4119A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004119. PMC 2612741. PMID 19127298.

- ^ Stresemann, E (1969). "Die Mauser von Emberiza rnelanocephala und Emberiza bruniceps". Journal für Ornithologie (in German). 110 (3): 291–305. doi:10.1007/BF01671065.