Machine code

| Program execution |

|---|

| General concepts |

| Types of code |

| Compilation strategies |

| Notable runtimes |

|

| Notable compilers & toolchains |

|

In computer programming, machine code is computer code consisting of machine language instructions, which are used to control a computer's central processing unit (CPU). For conventional binary computers, machine code is the binary representation of a computer program which is actually read and interpreted by the computer. A program in machine code consists of a sequence of machine instructions (possibly interspersed with data).[1]

Each machine code instruction causes the CPU to perform a specific task. Examples of such tasks include:

- Load a word from memory to a CPU register

- Execute an arithmetic logic unit (ALU) operation on one or more registers or memory locations

- Jump or skip to an instruction that is not the next one

In general, each architecture family (e.g., x86, ARM) has its own instruction set architecture (ISA), and hence its own specific machine code language. There are exceptions, such as the VAX architecture, which includes optional support of the PDP-11 instruction set; the IA-64 architecture, which includes optional support of the IA-32 instruction set; and the PowerPC 615 microprocessor, which can natively process both PowerPC and x86 instruction sets.

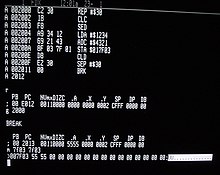

Machine code is a strictly numerical language, and it is the lowest-level interface to the CPU intended for a programmer. Assembly language provides a direct map between the numerical machine code and a human-readable mnemonic. In assembly, numerical opcodes and operands are replaced with mnemonics and labels. For example, the x86 architecture has available the 0x90 opcode; it is represented as NOP in the assembly source code. While it is possible to write programs directly in machine code, managing individual bits and calculating numerical addresses is tedious and error-prone. Therefore, programs are rarely written directly in machine code. However, an existing machine code program may be edited if the assembly source code is not available.

The majority of programs today are written in a high-level language. A high-level program may be translated into machine code by a compiler.

Instruction set

[edit]Every processor or processor family has its own instruction set. Instructions are patterns of bits, digits, or characters that correspond to machine commands. Thus, the instruction set is specific to a class of processors using (mostly) the same architecture. Successor or derivative processor designs often include instructions of a predecessor and may add new additional instructions. Occasionally, a successor design will discontinue or alter the meaning of some instruction code (typically because it is needed for new purposes), affecting code compatibility to some extent; even compatible processors may show slightly different behavior for some instructions, but this is rarely a problem. Systems may also differ in other details, such as memory arrangement, operating systems, or peripheral devices. Because a program normally relies on such factors, different systems will typically not run the same machine code, even when the same type of processor is used.

A processor's instruction set may have fixed-length or variable-length instructions. How the patterns are organized varies with the particular architecture and type of instruction. Most instructions have one or more opcode fields that specify the basic instruction type (such as arithmetic, logical, jump, etc.), the operation (such as add or compare), and other fields that may give the type of the operand(s), the addressing mode(s), the addressing offset(s) or index, or the operand value itself (such constant operands contained in an instruction are called immediate).[2]

Not all machines or individual instructions have explicit operands. On a machine with a single accumulator, the accumulator is implicitly both the left operand and result of most arithmetic instructions. Some other architectures, such as the x86 architecture, have accumulator versions of common instructions, with the accumulator regarded as one of the general registers by longer instructions. A stack machine has most or all of its operands on an implicit stack. Special purpose instructions also often lack explicit operands; for example, CPUID in the x86 architecture writes values into four implicit destination registers. This distinction between explicit and implicit operands is important in code generators, especially in the register allocation and live range tracking parts. A good code optimizer can track implicit and explicit operands which may allow more frequent constant propagation, constant folding of registers (a register assigned the result of a constant expression freed up by replacing it by that constant) and other code enhancements.

Assembly languages

[edit]

A much more human-friendly rendition of machine language, named assembly language, uses mnemonic codes to refer to machine code instructions, rather than using the instructions' numeric values directly, and uses symbolic names to refer to storage locations and sometimes registers.[3] For example, on the Zilog Z80 processor, the machine code 00000101, which causes the CPU to decrement the B general-purpose register, would be represented in assembly language as DEC B.[4]

Examples

[edit]IBM 709x

[edit]The IBM 704, 709, 704x and 709x store one instruction in each instruction word; IBM numbers the bit from the left as S, 1, ..., 35. Most instructions have one of two formats:

- Generic

- S,1-11

- 12-13 Flag, ignored in some instructions

- 14-17 unused

- 18-20 Tag

- 21-35 Y

- Index register control, other than TSX

- S,1-2 Opcode

- 3-17 Decrement

- 18-20 Tag

- 21-35 Y

For all but the IBM 7094 and 7094 II, there are three index registers designated A, B and C; indexing with multiple 1 bits in the tag subtracts the logical or of the selected index registers and loading with multiple 1 bits in the tag loads all of the selected index registers. The 7094 and 7094 II have seven index registers, but when they are powered on they are in multiple tag mode, in which they use only the three of the index registers in a fashion compatible with earlier machines, and require a Leave Multiple Tag Mode (LMTM) instruction in order to access the other four index registers.

The effective address is normally Y-C(T), where C(T) is either 0 for a tag of 0, the logical or of the selected index regisrs in multiple tag mode or the selected index register if not in multiple tag mode. However, the effective address for index register control instructions is just Y.

A flag with both bits 1 selects indirect addressing; the indirect address word has both a tag and a Y field.

In addition to transfer (branch) instructions, these machines have skip instruction that conditionally skip one or two words, e.g., Compare Accumulator with Storage (CAS) does a three way compare and conditionally skips to NSI, NSI+1 or NSI+2, depending on the result.

MIPS

[edit]The MIPS architecture provides a specific example for a machine code whose instructions are always 32 bits long.[5]: 299 The general type of instruction is given by the op (operation) field, the highest 6 bits. J-type (jump) and I-type (immediate) instructions are fully specified by op. R-type (register) instructions include an additional field funct to determine the exact operation. The fields used in these types are:

6 5 5 5 5 6 bits [ op | rs | rt | rd |shamt| funct] R-type [ op | rs | rt | address/immediate] I-type [ op | target address ] J-type

rs, rt, and rd indicate register operands; shamt gives a shift amount; and the address or immediate fields contain an operand directly.[5]: 299–301

For example, adding the registers 1 and 2 and placing the result in register 6 is encoded:[5]: 554

[ op | rs | rt | rd |shamt| funct]

0 1 2 6 0 32 decimal

000000 00001 00010 00110 00000 100000 binary

Load a value into register 8, taken from the memory cell 68 cells after the location listed in register 3:[5]: 552

[ op | rs | rt | address/immediate] 35 3 8 68 decimal 100011 00011 01000 00000 00001 000100 binary

Jumping to the address 1024:[5]: 552

[ op | target address ]

2 1024 decimal

000010 00000 00000 00000 10000 000000 binary

Overlapping instructions

[edit]On processor architectures with variable-length instruction sets[6] (such as Intel's x86 processor family) it is, within the limits of the control-flow resynchronizing phenomenon known as the Kruskal count,[7][6][8][9][10] sometimes possible through opcode-level programming to deliberately arrange the resulting code so that two code paths share a common fragment of opcode sequences.[nb 1] These are called overlapping instructions, overlapping opcodes, overlapping code, overlapped code, instruction scission, or jump into the middle of an instruction.[11][12][13]

In the 1970s and 1980s, overlapping instructions were sometimes used to preserve memory space. One example were in the implementation of error tables in Microsoft's Altair BASIC, where interleaved instructions mutually shared their instruction bytes.[14][6][11] The technique is rarely used today, but might still be necessary to resort to in areas where extreme optimization for size is necessary on byte-level such as in the implementation of boot loaders which have to fit into boot sectors.[nb 2]

It is also sometimes used as a code obfuscation technique as a measure against disassembly and tampering.[6][9]

The principle is also used in shared code sequences of fat binaries which must run on multiple instruction-set-incompatible processor platforms.[nb 1]

This property is also used to find unintended instructions called gadgets in existing code repositories and is used in return-oriented programming as alternative to code injection for exploits such as return-to-libc attacks.[15][6]

Relationship to microcode

[edit]In some computers, the machine code of the architecture is implemented by an even more fundamental underlying layer called microcode, providing a common machine language interface across a line or family of different models of computer with widely different underlying dataflows. This is done to facilitate porting of machine language programs between different models. An example of this use is the IBM System/360 family of computers and their successors.

Relationship to bytecode

[edit]Machine code is generally different from bytecode (also known as p-code), which is either executed by an interpreter or itself compiled into machine code for faster (direct) execution. An exception is when a processor is designed to use a particular bytecode directly as its machine code, such as is the case with Java processors.

Machine code and assembly code are sometimes called native code when referring to platform-dependent parts of language features or libraries.[16]

Storing in memory

[edit]From the point of view of the CPU, machine code is stored in RAM, but is typically also kept in a set of caches for performance reasons. There may be different caches for instructions and data, depending on the architecture.

The CPU knows what machine code to execute, based on its internal program counter. The program counter points to a memory address and is changed based on special instructions which may cause programmatic branches. The program counter is typically set to a hard coded value when the CPU is first powered on, and will hence execute whatever machine code happens to be at this address.

Similarly, the program counter can be set to execute whatever machine code is at some arbitrary address, even if this is not valid machine code. This will typically trigger an architecture specific protection fault.

The CPU is oftentimes told, by page permissions in a paging based system, if the current page actually holds machine code by an execute bit — pages have multiple such permission bits (readable, writable, etc.) for various housekeeping functionality. E.g. on Unix-like systems memory pages can be toggled to be executable with the mprotect() system call, and on Windows, VirtualProtect() can be used to achieve a similar result. If an attempt is made to execute machine code on a non-executable page, an architecture specific fault will typically occur. Treating data as machine code, or finding new ways to use existing machine code, by various techniques, is the basis of some security vulnerabilities.

Similarly, in a segment based system, segment descriptors can indicate whether a segment can contain executable code and in what rings that code can run.

From the point of view of a process, the code space is the part of its address space where the code in execution is stored. In multitasking systems this comprises the program's code segment and usually shared libraries. In multi-threading environment, different threads of one process share code space along with data space, which reduces the overhead of context switching considerably as compared to process switching.

Readability by humans

[edit]Various tools and methods exist to decode machine code back to its corresponding source code.

Machine code can easily be decoded back to its corresponding assembly language source code because assembly language forms a one-to-one mapping to machine code.[17] The assembly language decoding method is called disassembly.

Machine code may be decoded back to its corresponding high-level language under two conditions:

The first condition is to accept an obfuscated reading of the source code. An obfuscated version of source code is displayed if the machine code is sent to a decompiler of the source language.

The second condition requires the machine code to have information about the source code encoded within. The information includes a symbol table that contains debug symbols. The symbol table may be stored within the executable, or it may exist in separate files. A debugger can then read the symbol table to help the programmer interactively debug the machine code in execution.

- The SHARE Operating System (1959) for the IBM 709, IBM 7090, and IBM 7094 computers allowed for an loadable code format named SQUOZE. SQUOZE was a compressed binary form of assembly language code and included a symbol table.

- Modern IBM mainframe operating systems, such as z/OS, have available a symbol table named Associated data (ADATA). The table is stored in a file that can be produced by the IBM High-Level Assembler (HLASM),[18] IBM's COBOL compiler,[19] and IBM's PL/I compiler.[20]

- Microsoft Windows has available a symbol table[21] that is stored in a program database (

.pdb) file.[22] - Most Unix-like operating systems have available symbol table formats named stabs and DWARF. In macOS and other Darwin-based operating systems, the debug symbols are stored in DWARF format in a separate

.dSYMfile.

See also

[edit]- Assembly language

- Endianness

- List of machine languages

- Machine code monitor

- Overhead code

- P-code machine

- Reduced instruction set computer (RISC)

- Very long instruction word

- Teaching Machine Code: Micro-Professor MPF-I

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b While overlapping instructions on processor architectures with variable-length instruction sets can sometimes be arranged to merge different code paths back into one through control-flow resynchronization, overlapping code for different processor architectures can sometimes also be crafted to cause execution paths to branch into different directions depending on the underlying processor, as is sometimes used in fat binaries.

- ^ For example, the DR-DOS master boot records (MBRs) and boot sectors (which also hold the partition table and BIOS Parameter Block, leaving less than 446 respectively 423 bytes for the code) were traditionally able to locate the boot file in the FAT12 or FAT16 file system by themselves and load it into memory as a whole, in contrast to their counterparts in DOS, MS-DOS, and PC DOS, which instead rely on the system files to occupy the first two directory entry locations in the file system and the first three sectors of IBMBIO.COM to be stored at the start of the data area in contiguous sectors containing a secondary loader to load the remainder of the file into memory (requiring SYS to take care of all these conditions). When FAT32 and logical block addressing (LBA) support was added, Microsoft even switched to require i386 instructions and split the boot code over two sectors for code size reasons, which was no option to follow for DR-DOS as it would have broken backward- and cross-compatibility with other operating systems in multi-boot and chain load scenarios, and as with older IBM PC–compatible PCs. Instead, the DR-DOS 7.07 boot sectors resorted to self-modifying code, opcode-level programming in machine language, controlled utilization of (documented) side effects, multi-level data/code overlapping and algorithmic folding techniques to still fit everything into a physical sector of only 512 bytes without giving up any of their extended functions.

References

[edit]- ^ Stallings, William (2015). Computer Organization and Architecture 10th edition. Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 776. ISBN 9789332570405.

- ^ Kjell, Bradley. "Immediate Operand".

- ^ Dourish, Paul (2004). Where the Action is: The Foundations of Embodied Interaction. MIT Press. p. 7. ISBN 0-262-54178-5. Retrieved 2023-03-05.

- ^ Zaks, Rodnay (1982). Programming the Z80 (Third Revised ed.). Sybex. pp. 67, 120, 609. ISBN 0-89588-094-6. Retrieved 2023-03-05.

- ^ a b c d e Harris, David; Harris, Sarah L. (2007). Digital Design and Computer Architecture. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers. ISBN 978-0-12-370497-9. Retrieved 2023-03-05.

- ^ a b c d e Jacob, Matthias; Jakubowski, Mariusz H.; Venkatesan, Ramarathnam [at Wikidata] (20–21 September 2007). Towards Integral Binary Execution: Implementing Oblivious Hashing Using Overlapped Instruction Encodings (PDF). Proceedings of the 9th workshop on Multimedia & Security (MM&Sec '07). Dallas, Texas, US: Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 129–140. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.69.5258. doi:10.1145/1288869.1288887. ISBN 978-1-59593-857-2. S2CID 14174680. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-09-04. Retrieved 2021-12-25. (12 pages)

- ^ Lagarias, Jeffrey "Jeff" Clark; Rains, Eric Michael; Vanderbei, Robert J. (2009) [2001-10-13]. Brams, Stephen; Gehrlein, William V.; Roberts, Fred S. (eds.). "The Kruskal Count". The Mathematics of Preference, Choice and Order. Essays in Honor of Peter J. Fishburn. Berlin / Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag: 371–391. arXiv:math/0110143. ISBN 978-3-540-79127-0. (22 pages)

- ^ Andriesse, Dennis; Bos, Herbert [at Wikidata] (2014-07-10). Written at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Dietrich, Sven (ed.). Instruction-Level Steganography for Covert Trigger-Based Malware (PDF). 11th International Conference on Detection of Intrusions and Malware, and Vulnerability Assessment (DIMVA). Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Egham, UK; Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. pp. 41–50 [45]. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-08509-8_3. eISSN 1611-3349. ISBN 978-3-31908508-1. ISSN 0302-9743. S2CID 4634611. LNCS 8550. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-08-26. Retrieved 2023-08-26. (10 pages)

- ^ a b Jakubowski, Mariusz H. (February 2016). "Graph Based Model for Software Tamper Protection". Microsoft. Archived from the original on 2019-10-31. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ^ Jämthagen, Christopher (November 2016). On Offensive and Defensive Methods in Software Security (PDF) (Thesis). Lund, Sweden: Department of Electrical and Information Technology, Lund University. p. 96. ISBN 978-91-7623-942-1. ISSN 1654-790X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-08-26. Retrieved 2023-08-26. (1+xvii+1+152 pages)

- ^ a b "Unintended Instructions on x86". Hacker News. 2021. Archived from the original on 2021-12-25. Retrieved 2021-12-24.

- ^ Kinder, Johannes (2010-09-24). Static Analysis of x86 Executables [Statische Analyse von Programmen in x86 Maschinensprache] (PDF) (Dissertation). Munich, Germany: Technische Universität Darmstadt. D17. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2021-12-25. (199 pages)

- ^ "What is "overlapping instructions" obfuscation?". Reverse Engineering Stack Exchange. 2013-04-07. Archived from the original on 2021-12-25. Retrieved 2021-12-25.

- ^ Gates, William "Bill" Henry, Personal communication (NB. According to Jacob et al.)

- ^ Shacham, Hovav (2007). The Geometry of Innocent Flesh on the Bone: Return-into-libc without Function Calls (on the x86) (PDF). Proceedings of the ACM, CCS 2007. ACM Press. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-12-15. Retrieved 2021-12-24.

- ^ "Managed, Unmanaged, Native: What Kind of Code Is This?". developer.com. 2003-04-28. Retrieved 2008-09-02.

- ^ Tanenbaum, Andrew S. (1990). Structured Computer Organization, Third Edition. Prentice Hall. p. 398. ISBN 978-0-13-854662-5.

- ^ "Associated Data Architecture". High Level Assembler and Toolkit Feature.

- ^ "COBOL SYSADATA file contents". Enterprise COBOL for z/OS.

- ^ "SYSADATA message information". Enterprise PL/I for z/OS 6.1 information.

- ^ "Symbols for Windows debugging". Microsoft Learn. 2022-12-20.

- ^ "Querying the .Pdb File". Microsoft Learn. 2024-01-12.

Further reading

[edit]- Hennessy, John L.; Patterson, David A. (1994). Computer Organization and Design. The Hardware/Software Interface. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers. ISBN 1-55860-281-X.

- Tanenbaum, Andrew S. (1999). Structured Computer Organization. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-020435-8.

- Brookshear, J. Glenn (2007). Computer Science: An Overview. Addison Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-38701-1.