Pickelhaube

The Pickelhaube (German: [ˈpɪkl̩ˌhaʊ̯bə] ; pl. Pickelhauben, pronounced [ˈpɪkl̩ˌhaʊ̯bn̩] ; from German: Pickel, lit. 'point' or 'pickaxe', and Haube, lit. 'bonnet', a general word for "headgear"), also Pickelhelm, is a spiked leather or metal helmet that was worn in the 19th and 20th centuries by Prussian and German soldiers of all ranks, as well as firefighters and police. Although it is typically associated with the Prussian Army, which adopted it in 1842–43,[1] the helmet was widely imitated by other armies during that period.[2] It is still worn today as part of ceremonial wear in the militaries of certain countries, such as Sweden, Chile, and Colombia.

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]

Derivation of title

[edit]The designation Pickelhaube is believed to be originally derived from Bickel haute - a medieval helmet of broadly similar shape.[3]

Russian helmet

[edit]During the 1830s, Tsar Nicholas I of Russia decided to replace the shako infantry caps. For this, he commissioned General Lev Ivanovich Kiel, a member of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts, to design the new headdress for the Russian infantry. The new headwear was inspired by the leather helmet worn by the Russian cuirassiers, with the plumed crest being replaced by a pointed ornament in the shape of a flaming grenade.[4]

Prussian helmet

[edit]The origins of the Prussian helmet began with a visit to Russia by Prince Charles of Prussia in 1837. During the visit, the Tsar presented Charles with the new helmet, which was still in its project stage. The Prince liked the idea, and upon returning to Berlin he proposed it to his father, King Frederick William III of Prussia. The King, however, did not approve of the helmet which he considered expensive and unnecessary. After his death in 1840, the new king Frederick William IV approved his younger brother's idea, and the Prussian army officially adopted the spiked helmet in 1842, thus ahead of the Russian project which was still being worked on;[4] Russia finally adopted the helmet in 1844.[5]

Adoption

[edit]Frederick William IV introduced the Pickelhaube for use by the majority of Prussian infantry on 23 October 1842 by a royal cabinet order.[6] The use of the Pickelhaube spread rapidly to other German principalities. Oldenburg adopted it by 1849, Baden by 1870, and in 1887, the Kingdom of Bavaria was the last German state to adopt the Pickelhaube (since the Napoleonic Wars, they had had their own design of helmet called the Raupenhelm, a Tarleton helmet). Amongst other European armies, that of Sweden adopted the Prussian version of the spiked helmet in 1845,[7] in Wallachia it was decided to adopt the helmet on 15 August 1845, possibly being influenced by the visit of Prince Albert of Prussia. However, its introduction to the troops took longer, while Moldavia adopted the Russian version of the spiked helmet in the same year, possibly under the influence of the Tsarist Army.[4]

From the second half of the 19th century onwards, the armies of a number of nations including Argentina,[8] Bolivia, Colombia, Chile, Ecuador, Mexico, Portugal, Norway, and Venezuela adopted the Pickelhaube or something very similar.[7] The popularity of this headdress in Latin America arose from a period when military missions from Imperial Germany were widely employed to train and organize national armies. The Peruvian Army was the first of these, when some pickelhaubes were shipped to the country in the 1870s. During the War of the Pacific, the 6th Infantry Regiment "Chacabuco" became the first Chilean military unit to adopt this headdress, using captured Peruvian stocks.[9]

The Russian version initially had a horsehair plume fitted to the end of the spike, but this was later discarded in some units. The Russian spike was topped with a grenade motif. At the beginning of the Crimean War, such helmets were common among infantry and grenadiers, but soon fell out of place in favour of the forage cap. After 1862 the spiked helmet ceased to be generally worn by the Russian Army, although it was retained until 1914 by the Cuirassier regiments of the Imperial Guard, and the Gendarmerie. The Soviets prolonged the history of the pointed military headgear with their own cloth Budenovka adopted in 1919 by the Red Army.[10]

Derivatives

[edit]

In 1847, the Household Cavalry, along with British dragoons and Dragoon Guards, adopted a helmet which was a hybrid between the Pickelhaube and the traditional dragoon helmet which it replaced. This "Albert Pattern" helmet was named after Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha who took a keen interest in military uniforms, and featured a falling horsehair plume which could be removed when on campaign. It was adopted by other heavy cavalry regiments across the British Empire and remains in ceremonial use.[11] The Pickelhaube also influenced the design of the British army Home Service helmet, as well as the custodian helmet still worn by police in England and Wales.[12] The linkage between Pickelhaube and Home Service helmet was however not a direct one, since the British headdress was higher, had only a small spike and was made of stiffened cloth over a cork framework, instead of leather. Both the United States Army and Marine Corps wore helmets of the British pattern for full dress between 1881 and 1902.

Design

[edit]The basic Pickelhaube was made of hardened (boiled) leather, given a glossy-black finish, and reinforced with metal trim (usually plated with gold or silver for officers) that included a metal spike at the crown. Early versions had a high crown, but the height gradually was reduced and the helmet became more fitted in form, in a continuing process of weight-reduction and cost-saving. In 1867, a further attempt at weight reduction by removing the metal binding of the front peak, and the metal reinforcing band on the rear of the crown (which also concealed the stitched rear seam of the leather crown), did not prove successful.

The version of the Pickelhaube worn by Prussian artillery units employed a ball-shaped finial rather than the pointed spike, a modification ordered in 1844 because of injuries to horses and damage to equipment caused by the latter.[13] Prior to the outbreak of World War I in 1914 detachable black or white plumes were worn with the Pickelhaube in full dress by German generals, staff officers, dragoon regiments, infantry of the Prussian Guard and a number of line infantry regiments as a special distinction. This was achieved by unscrewing the spike (a feature of all Pickelhauben regardless of whether they bore a plume) and replacing it with a tall metal plume-holder known as a trichter. For musicians of these units, and also for Bavarian Artillery and an entire cavalry regiment of the Saxon Guard, this plume was red.

Aside from the spike finial, perhaps the most recognizable feature of the Pickelhaube was the ornamental front plate, which denoted the regiment's province or state. The most common plate design consisted of a large, spread-winged eagle, the emblem used by Prussia. Different plate designs were used by Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden, and the other German states. The Russians used the traditional double-headed eagle.

German military Pickelhauben also mounted two round, colored cockades behind the chinstraps attached to the sides of the helmet. The right cockade, the national cockade, was red, black and white. The left cockade was used to denote the state of the soldier (Prussia: black and white; Bavaria: white and blue; etc.).

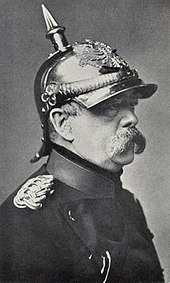

All-metal versions of the Pickelhaube were worn mainly by cuirassiers, and often appear in portraits of high-ranking military and political figures (such as Otto von Bismarck, pictured above). These helmets were sometimes referred to as lobster-tail helmets, due to their distinctive articulated neck guard. The design of these is based on cavalry helmets in common use since the 16th century, but with some features taken from the leather helmets. The version worn by the Prussian Gardes du Corps was of tombac (copper and zinc alloy) with silver mountings. That worn by the cuirassiers of the line since 1842 was of polished steel with brass mountings.

Cover

[edit]

In 1892, a light brown cloth helmet cover, the M1892 Überzug, became standard issue for all Pickelhauben for manoeuvres and active service. The Überzug was intended to protect the helmet from dirt and reduce its combat visibility, as the brass and silver fittings on the Pickelhaube proved to be highly reflective.[14] Regimental numbers were sewn or stenciled in red (green from August 1914) onto the front of the cover, other than in units of the Prussian Guards, which never carried regimental numbers or other adornments on the Überzug. With exposure to the sun, the Überzug faded into a tan shade. In October 1916 the colour was changed to feldgrau (field grey), although by that date, the plain metal Stahlhelm was standard issue for most troops.

World War I

[edit]All helmets produced for the infantry before and during 1914 were made of leather. As the war progressed, Germany's leather stockpiles dwindled. After extensive imports from South America, particularly Argentina, the German government began producing ersatz Pickelhauben made of other materials. In 1915, some Pickelhauben started to be constructed from thin sheet steel. However, the German high command needed to produce an even greater number of helmets, leading to the usage of pressurized felt and even paper to construct Pickelhauben. The Pickelhaube was discontinued in 1916.[15]

During the early months of World War I, it was soon discovered that the Pickelhaube did not measure up to the demanding conditions of trench warfare. The leather helmets offered little protection against shell fragments and shrapnel and the conspicuous spike made its wearer a target. These shortcomings, combined with material shortages, led to the introduction of the simplified model 1915 helmet described above, with a detachable spike. In September 1915 it was ordered that the new helmets were to be worn without spikes when in the front line.[16]

Beginning in 1916, the Pickelhaube was slowly replaced by a new German steel helmet (the Stahlhelm) intended to offer greater head protection from shell fragments. After the adoption of the Stahlhelm, the Pickelhaube was reduced to limited ceremonial wear by senior officers away from the war zones; plus the Leibgendarmerie S.M. des Kaisers whose role as an Imperial/Royal escort led them to retain peacetime full dress throughout the war.[17][18] With the collapse of the German Empire in 1918, the Pickelhaube ceased to be part of the military uniform, and even the police adopted shakos of a Jäger style. In modified forms the new Stahlhelm helmet would continue to be worn by German troops into World War II.

-

Kaiser Wilhelm II, August von Mackensen and others wearing Pickelhauben with cloth covers in 1915

-

The Pickelhaube was often used in propaganda against the Germans as in this World War I poster (Harry R. Hopps; 1917).

Current use

[edit]

The Pickelhaube is still part of the parade/ceremonial uniform of the Life Guards of Sweden, the National Republican Guard (GNR) of Portugal, King's Guard of Thailand, the military academies of Chile, Colombia, Venezuela and Ecuador, the Military College of Bolivia, the Army Central Band and Army School Bands of Chile, the Chilean Army's 1st Cavalry and 1st Artillery Regiments, and the Presidential Guard Battalion and National Police of Colombia. The Blues and Royals, the Life Guards of the United Kingdom and traffic police in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan also use different forms of the Pickelhaube. The modern Romanian Gendarmerie (Jandarmeria Româna) maintain a mounted detachment who wear a white plumed Pickelhaube of a model dating from the late 19th century, as part of their ceremonial uniform.

As a cultural icon

[edit]As early as 1844, the poet Heinrich Heine mocked the Pickelhaube as a symbol of reaction and an unsuitable head-dress. He cautioned that the spike could easily "draw modern lightnings down on your romantic head".[19] The poem was part of his political satire on the contemporary monarchy, national chauvinism, and militarism, used aggressively against democratic movements, entitled Germany. A Winter's Tale.

In the lead-up to the 2006 FIFA World Cup in Germany, a molded plastic version of the Pickelhaube was available as a fanware article. The common model was colored in the black-red-gold of the German flag, with a variety of other colors also available.[citation needed]

The spiked helmet remained part of a clichéd mental picture of Imperial Germany as late as the inter-war period even after the headdress had ceased to be worn. This was possibly because of the extensive use of the pickelhaube in Allied propaganda before and during World War I, although the helmet had been a well known icon of Imperial Germany even prior to 1914. Pickelhauben were popular targets for Allied souvenir hunters during the early months of the war.[citation needed][20]

Gallery

[edit]-

Ceremonial nickel-plated Pickelhaube of the modern Swedish Royal Life Guard Regiments.

-

First Infantry Regiment of the Royal Guard, Grand Palace, Bangkok, Thailand

-

National Republican Guard, São Bento Palace, Lisbon, Portugal

-

Colombian military band at Monument of Fallen Soldiers and Police in Bogota

-

Lancers of the modern Chilean Presidential Escort Regiment

-

German Reenactors wearing full dress Imperial German uniforms

-

Spanish Cuirassier Helmet

-

Peruvian artillery soldier of the War of the Pacific era.

-

Plastic novelty helmet modeled after the Pickelhaube

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Knotel, Richard (1980). Uniforms of the World. p. 129. ISBN 0-684-16304-7.

- ^ See "The American Pickelhaube" Archived 2009-02-02 at the Wayback Machine for examples of American military Pickelhaube.

- ^ Carman, W.Y. (1977). A Dictionary of Military Uniform. Scribner. p. 101. ISBN 0-684-15130-8.

- ^ a b c Dr. Horia Șerbănescu (30 April 2021). "Primele căști ale infanteriei române". Facebook (in Romanian). Muzeul Militar Național "Regele Ferdinand I". Archived from the original on 2022-02-26.

- ^ Complete Collection of Laws of the Russian Empire (in Russian). p. 334.

- ^ The Model 1842 Pickelhaube Archived 2007-05-21 at the Wayback Machine from the Kaiser's Bunker web site.

- ^ a b Knötel, Richard; Knötel, Herbert; Sieg, Herbert (1980). Uniforms of the World. ISBN 0-684-16304-7.

- ^ Jara Franco, Ricardo (18 August 2011). "PICKELHAUBEN IN LATIN AMERICA". Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- ^ "Colonel J's - Articles -Latin American". www.pickelhauben.net. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ Khvostov, Mikhail (15 May 1996). The Russian Civil War (1) The Red Army. Bloomsbury USA. p. 46. ISBN 1-85532-608-6.

- ^ Wood, Stephen (2015). Those Terrible Grey Horses: An Illustrated History of the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards. Osprey Publishing. p. 82. ISBN 978-1472810625.

- ^ Major R. M. Barnes, p. 257, "A History of the Regiments & Uniforms of the British Army, First Sphere Books, 1972.

- ^ Herr, Ulrich (2016). The German Artillery from 1871 to 1914. Verlag Militaria GmbH. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-3-902526-80-9.

- ^ First World War, Willmott, H. P., Dorling Kindersley, 2003, p. 59.

- ^ "Get the Point? — A Brief History of Germany's 'Pickelhaube' Spiked Helmet". MilitaryHistoryNow.com. 2012-05-27. Archived from the original on 2017-11-12. Retrieved 2017-11-12.

- ^ World War One German Army, Stephen Bull, pp. 71–73.

- ^ Charles Woolley, p. 368, Uniforms and Equipment of the Imperial German Army 1900–1918, ISBN 0-7643-0935-8.

- ^ Andrew Mollo, p. 191, Army Uniforms of World War I, ISBN 0-668-04479-9.

- ^ Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen. Caput III Archived 2013-07-03 at the Wayback Machine Deutschelyric.de, retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ^ Saunders, Nicholas (2016). "'Pearl's Treasure': The Trench Art Collection of an Australian Sapper" (PDF). Sappers & Shrapnel: Contemporary Art and the Art of the Trenches: 12–39 – via Academia.[permanent dead link]

External links

[edit]- 1840s fashion

- 1850s fashion

- 1860s fashion

- 1870s fashion

- 1880s fashion

- 1890s fashion

- 1900s fashion

- 1910s fashion

- 19th-century fashion

- Combat helmets of Germany

- Franco-Prussian War

- German military uniforms

- Military history of Germany

- Prussian Army

- World War I military equipment of Germany

- Nicholas I of Russia

- Frederick William IV of Prussia