Randy Weaver

Randy Weaver | |

|---|---|

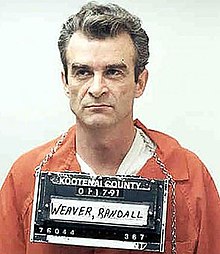

Mugshot, taken January 17, 1991 | |

| Born | January 3, 1948 Villisca, Iowa, U.S. |

| Died | May 11, 2022 (aged 74) |

| Other names | Pete Weaver |

| Education | Iowa Central Community College (dropped out) University of Northern Iowa (dropped out) |

| Known for | Ruby Ridge siege |

| Spouses | Vicki Jordison

(m. 1971; died 1992)Linda Gross (m. 1999) |

| Children | 4 |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1968–1970 |

| Rank | Sergeant |

| Awards | National Defense Service Medal |

| Signature | |

Randall Claude Weaver (January 3, 1948 – May 11, 2022) was an American survivalist.[1] He was a central actor in the 1992 Ruby Ridge standoff with federal agents at his cabin near Naples, Idaho, during which his wife and son were killed.[2][3] Weaver was charged with murder, conspiracy, and assault as well as other crimes. He was acquitted of most of the charges, but was convicted of failing to appear in court on a previous weapons charge and sentenced to 18 months in prison.[1] He and his family eventually received a total of $3.1 million in compensation for the killing of his wife and son by federal agents.[4]

Early life

Randy Weaver was born on January 3, 1948, to Clarence and Wilma Weaver, a farming couple in Villisca, Iowa. He was one of four children.[5][6] The Weavers were deeply religious and had difficulty finding a denomination that matched their views; they often moved around among Evangelical, Presbyterian, and Baptist churches.[7][page needed]

After graduating from Jefferson High School in 1966, he attended Iowa Central Community College for two years. In 1968, he dropped out to enlist in the United States Army during the height of the Vietnam War. He was stationed at Fort Bragg in North Carolina.[3][8] While Weaver had told other people that he had been a Green Beret in the Army, his discharge papers showed that he had never been a member of the Green Berets or Special Forces, but may have received some general demolitions training as a combat engineer.[9]

In 1970, during a visit to his hometown while on leave, Weaver met his future wife Victoria "Vicki" Jordison. He introduced himself as "Pete", rather than his "hated" given name Randall.[7][page needed] He was discharged at the rank of sergeant on October 8, 1971, and married Vicki the following month.[10]

Ruby Ridge siege

Background

A month after leaving the Army, Randy Weaver and Vicki Jordison married in a ceremony at the First Congregationalist Church in Fort Dodge, Iowa, in November 1971. After a semester at the University of Northern Iowa, Randy dropped out after finding well-paying work at a local John Deere factory.[7][page needed] Vicki worked first as a secretary and then as a homemaker.[11]

Partially as a result of reading the 1978 book The Late Great Planet Earth, the couple began to harbor more Christian fundamentalist beliefs, with Vicki believing that the apocalypse was imminent.[7][page needed] To follow Vicki's vision of her family surviving the apocalypse away from what they saw as a corrupt civilization, the Weaver family moved to a 20-acre (8.1-hectare) property in remote Boundary County, Idaho, in 1983 and built a cabin there.[11] They paid $5,000 in cash ($13,000 in 2023[12]) and traded their moving truck for the land, valued at $500 an acre.[7][page needed]

In 1988, Weaver decided to run for county sheriff by using the slogan "Get out of jail – free" and he was adamant about his decision not to pay taxes.[13]

While the Weavers subscribed to ideas that broadly fell under the category of Christian Identity, their beliefs were still different.[14] Like many in that movement, Vicki Weaver developed a set of beliefs which were based on her adherence to Old Covenant Laws, and her family referred to God as Yahweh (see Sacred Name Movement). They also believed themselves to be Israelites.[15]

In 1989, Weaver met Kenneth Fadeley at a meeting of the white supremacist group Aryan Nations.[16] Fadeley was actually an undercover ATF agent investigating the Aryan Nation complex under the alias "Gus Magisano".[17] Weaver agreed to sell Fadeley two sawed-off shotguns, and was recorded on tape saying he could supply Fadelay with four or five illegal shotguns a week.[18] In December 1990, Weaver received felony weapons charges in connection with the 1989 transaction.[17] During the initial encounter with Fadeley, the Weaver family relocated from a rental house to a cabin near Ruby Ridge, Idaho, in the Selkirk mountains.[17] After charges were pressed against her husband, Vicki Weaver wrote to U.S. Attorney Maurice O. Ellsworth, addressing him as "Servant of the Queen of Babylon" and writing, "The stink of your lawless government has reached Heaven, the abode of Yahweh our Yashua", and "Whether we live or whether we die, we will not bow to your evil commandments."[19]

At the time of the Ruby Ridge siege, the Weavers had four children: Sara, 16; Samuel, 14; Rachel, 10; and Elisheba, 10 months. Vicki homeschooled the children.[11]

Siege

Ruby Ridge was the site of an 11-day police standoff in 1992 in Boundary County, Idaho, near Naples. It began on August 21, when deputies of the United States Marshals Service (USMS) initiated action to apprehend and arrest Randy Weaver under a bench warrant after his failure to appear on firearms charges.[11]

Weaver refused to surrender and remained at home with his family and friend Kevin Harris. The Hostage Rescue Team of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI HRT) became involved as the siege developed.[20]

During the Marshals Service reconnoiter of the Weaver property, six Marshals encountered Harris, and Randy's 14-year-old son, Sammy Weaver, in the woods near the family cabin. A shootout took place. Marshals shot the Weavers' dog Striker, then shot Sammy Weaver in the back as he ran away, killing him. During the firefight, Harris shot Deputy U.S. Marshal, William Francis Degan, in the chest, resulting in Degan's death.[7][page needed]

On August 22, 1992 FBI sniper/observers in the Hostage Rescue Team were dispatched to Ruby Ridge.[17] The team used specified "Rules of Engagement" which allowed them to shoot any armed adult male exiting the cabin.[13]

In the subsequent siege of the Weaver residence, led by the FBI, Weaver's wife Vicki was shot and killed[20] by an FBI sniper while standing in her home holding her 10-month-old daughter. Harris was critically wounded and almost died during the subsequent standoff. Weaver was shot once; he was not holding a weapon at the time.[11][21][22] All casualties occurred in the first two days of the operation. The siege and standoff were ultimately resolved by civilian negotiator, Bo Gritz, who was instrumental in getting Weaver to allow Harris to get medical attention. Harris surrendered and was arrested on August 30. Weaver and his three daughters surrendered the next day after being convinced by Gritz that there was no other sensible solution.[7][page needed]

Aftermath

Weaver was charged with multiple crimes relating to the Ruby Ridge incident — a total of ten counts, including the original firearms charges. Attorney, Gerry Spence, handled Weaver's defense, and successfully argued that Weaver's actions were justifiable as self-defense. Spence did not call any witnesses for the defense, rather focusing on attacking the credibility of FBI agents and forensic technicians.[23] The judge dismissed two counts after hearing prosecution witness testimony. The jury acquitted Weaver of all remaining charges except two, one of which the judge set aside. He was found guilty of one count, failure to appear, for which he was fined $10,000, and sentenced to 18 months in prison.[1] He was credited with time served plus an additional three months, and was then released. Kevin Harris was acquitted of all criminal charges.[7][page needed]

In August 1995, the US government avoided trial on a civil lawsuit filed by the Weavers by awarding the three surviving daughters $1,000,000 each, and Randy Weaver $100,000 over the deaths of Sammy and Vicki Weaver.[24]

Later life

Weaver testified about his racial beliefs before a U.S. Senate Judiciary subcommittee in 1995, saying, "I'm not a hateful racist as most people understand it. But I believe in the separation of races. We wanted to be separated from the rest of the world, to live in a remote area, to give our children a good place to grow up."[2]

In 1995, Weaver was interviewed by New York Times reporter, Ken Fuson, and expressed regret about not appearing in court for his 1991 gun charge, saying "I'm not totally without fault in this."[25]

In April 1996, Weaver accompanied Bo Gritz to Jordan, Montana, where Gritz was to attempt to negotiate a conclusion to the Montana Freemen standoff. However, Weaver was not allowed by the FBI to enter the Freemen's holdout.[26]

In 1998, Weaver published The Federal Siege at Ruby Ridge: In Our Own Words, which he partly sold in person at gun shows.[15]

In 1999, Weaver married Linda Gross, a legal secretary, in Jefferson, Iowa.[27]

On June 18, 2007, Weaver participated in a press conference with tax protesters, Edward and Elaine Brown, on the front porch of their home in Plainfield, New Hampshire.[28] He declared, "I ain't afraid of dying no more. I'm curious about the afterlife, and I'm an atheist."[29]

Death

Weaver's daughter, Sara, posted online that he had died on May 11, 2022, after being sick since at least mid-April. A cause of death was not given.[30][31] He was 74 years old.[32]

Appearance in media

A CBS miniseries about the Ruby Ridge incident, titled Ruby Ridge: An American Tragedy, aired on May 19 and 21, 1996.[33] It was based on the book Every Knee Shall Bow by reporter Jess Walter.[33] It starred Laura Dern as Vicki, Kirsten Dunst as Sara, and Randy Quaid as Randy.[34] Later that year, the television series was adapted into a full-length TV movie, The Siege at Ruby Ridge.[35]

PBS' American Experience aired an episode titled "Ruby Ridge" on February 14, 2017.[36]

See also

- The Covenant, the Sword, and the Arm of the Lord

- FBI Critical Incident Response Group

- Rainbow Farm

- Waco siege

References

- ^ a b c Faddis, Elizabeth (May 12, 2022). "Randy Weaver from Ruby Ridge standoff dies at 74". Denver Gazette. Washington Examiner. Archived from the original on May 14, 2022. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- ^ a b Jackson, Robert L. (September 7, 1995). "Militant Relives Idaho Tragedy for Senators: Probe: Randy Weaver admits Ruby Ridge errors, seeks 'accountability.'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 24, 2019. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ a b Risen, Clay (May 13, 2022). "Randy Weaver, Who Confronted U.S. Agents at Ruby Ridge, Dies at 74". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 14, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ^ Labaton, Stephen (August 16, 1995). "Separatist Family Given $3.1 Million From Government". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 13, 2022. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- ^ "Randy and Vicki Weaver: From heartland to disaster". nwitimes.com. Hearst Newspapers. August 27, 1995. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved March 30, 2019.

- ^ "The Incident at Ruby Ridge". seoklaw.com. Wagner & Lynch Law Firms. April 25, 2015. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Walter, Jess (2002). Ruby Ridge: The Truth and Tragedy of the Randy Weaver Family. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-000794-2.

- ^ Walter, Jess (1996). Every Knee Shall Bow. HarperCollins. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-06-101131-3.

- ^ "DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE REPORT ON INTERNAL REVIEW REGARDING THE RUBY RIDGE HOSTAGE SITUATION AND SHOOTINGS BY LAW ENFORCEMENT PERSONNEL". law2.umkc.edu. University of Missouri-Kansas City. Retrieved May 14, 2023.

- ^ Carter, Gregg Lee (2012). Guns in American Society: An Encyclopedia of History, Politics, Culture, and the Law. ABC-CLIO. p. 714. ISBN 978-0-313-38670-1. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Hewitt, Bill; Nelson, Margaret; Haederle, Michael; Slavin, Barbara (September 25, 1995). "A Time to Heal". People. 45 (13). Archived from the original on February 13, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- ^ Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ a b Wagner-Pacifici, Robin (2000). Theorizing the Standoff. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511488887. ISBN 978-0-521-65244-5.

- ^ "Ruby Ridge, Part One: Suspicion | American Experience". pbs.org. PBS. Archived from the original on April 15, 2022. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- ^ a b Hull, Anne (April 30, 2001). "Randy Weaver's Return From Ruby Ridge". The Washington Post. Washington D.C. Archived from the original on March 18, 2022. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- ^ Johnston, David (September 9, 1995). "Informer Says Siege Figure Offered to to[sic] Sell Him Illegal Guns". The New York Times. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Wagner-Pacifici, Robin (2000). Theorizing the Standoff. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511488887. ISBN 978-0-521-65244-5.

- ^ "Agents Deny Weaver Was Set Up Feds Say Separatist Brought Trouble On Himself | The Spokesman-Review". www.spokesman.com. Retrieved March 25, 2023.

- ^ Lei, George Lardner Jr; Richard (September 3, 1995). "Standoff at Ruby Ridge". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Morganthau, Tom; Isikoff, Michael; Cohn, Bob (August 28, 1995). "The Echoes of Ruby Ridge". Newsweek: 25–28. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2017. The three cited authors are absent from the linked webpage, but are added because this work is cited in a variety of other sources. For example, see citation [1] in Catherine (January 13, 1998). "How the Millennium Comes Violently". Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego: Department of Religious Studies, San Diego State University. Archived from the original on February 13, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- ^ State of Idaho v. Lon T. Horiuchi [1] (9th Cir. June 5, 2001), Text.

- ^ Goodman, Barak (February 14, 2017). "Ruby Ridge". American Experience. Season 29. Episode 6. Event occurs at 30:00. PBS. Archived from the original on July 24, 2017. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- ^ Spence, Gerry (1996). From Freedom to Slavery, the Rebirth of Freedom in America. St. Martin's Press.

- ^ Lardner, George Jr.; Thomas, Pierre (August 16, 1995). "US will pay family $3.1m for 1992 siege". The Boston Globe.

- ^ "Conversations / Randy Weaver; He's a Rallying Cry of the Far Right But a Reluctant Symbol". The New York Times. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ "'Bo' Gritz is Allowed to Meet with 'Freemen'". Los Angeles Times. April 28, 1996.

- ^ "Randy Weaver remarries, moves back to the Midwest". The Lewiston Tribune. Associated Press. July 15, 1999. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- ^ "$1M in Unpaid Taxes: Couple Dares Feds". ABC News. February 9, 2009. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- ^ Elliott, Philip (June 19, 2017). "Weaver backs fugitives, recalls Ruby Ridge". spokesman.com. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- ^ "Ruby Ridge Standoff: Randy Weaver has died at the age of 74". KULR-8 Local News. May 12, 2022. Archived from the original on May 12, 2022. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- ^ Luck, Melissa (May 12, 2022). "Randy Weaver, man at center of Ruby Ridge standoff, has died". KXLY. Archived from the original on May 12, 2022. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- ^ Geranios, Nicholas K. (May 12, 2022). "Randy Weaver, participant in Ruby Ridge standoff, dies at 74". Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 13, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ^ a b Walter, Jess (1996) [1995]. Every Knee Shall Bow: The Truth and Tragedy of Ruby Ridge and the Randy Weaver Family. New York: HarperPaperbacks. p. 190. ISBN 0-06-101131-2. Retrieved February 7, 2017. The link to this title is to the 1996 edition.

- ^ Suprynowicz, Vin (1999). "The Courtesan Press, Eager Lapdogs to Tyranny [Ch. 6]". Send in the Waco Killers: Essays on the Freedom Movement, 1993–1998. Pahrump, NV: Mountain Media. pp. 288–291. ISBN 0-9670259-0-7. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ Young, Roger (director), Chetwynd, Lionel (screenwriter) et al. (2007). Standoff at Ruby Ridge. Edgar J. Scherick Associates, Regan Company, Victor Television Productions (producers). Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- ^ Hale, Mike (February 13, 2017). "'Ruby Ridge' Revisits a 1992 Siege With Current Resonance". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 12, 2022. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

External links

- "Idaho vs Randy Weaver" from the CourtTV Crime Library

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Summary of an Appeals Court ruling on Horiuchi; includes Special Rules of Engagement and a dissent by Judge Alex Kozinski

- 1948 births

- 2022 deaths

- Christian Identity

- American atheists

- Members of the United States Army Special Forces

- American people acquitted of murder

- Entrapment

- People from Montgomery County, Iowa

- United States Army soldiers

- People from Boundary County, Idaho

- Military personnel from Iowa

- American prisoners and detainees

- American former Christians

- American white separatists

- American white supremacists

- Survivalists

- United States Army personnel of the Vietnam War

- Prisoners and detainees of the United States federal government